How Looting Created a Weather Blindspot in the Venezuelan Amazon

Maduro just ordered electricity rationing and reduced working hours for public offices. But the climate emergency he used as the excuse can’t be observed at the region that feeds the country’s main hydroelectric reservoir

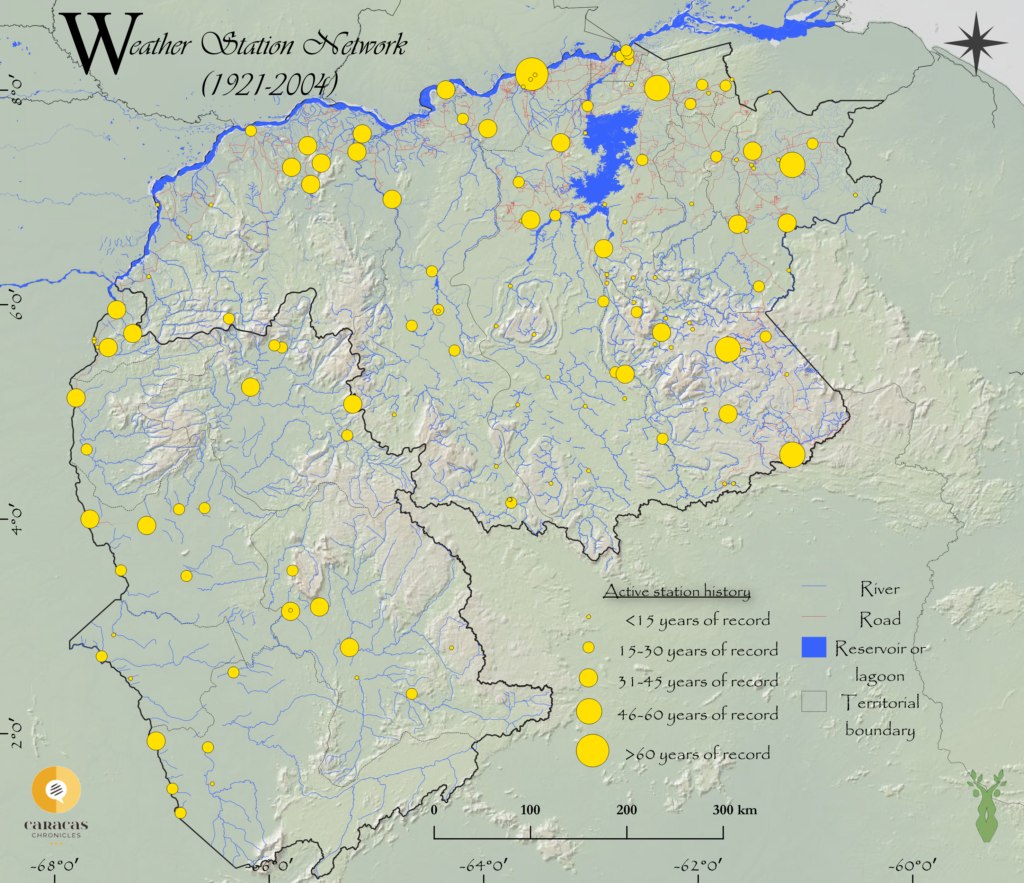

Gone are those times, from the 1960s to the 1980s, when Venezuela deployed most of its weather stations, then managed by the Environment Ministry and the air force’s weather service. At least 148 stations were installed in Guayana and the Venezuelan Amazon, that sparsely-populated southern half of the country, larger than Germany, where great rivers like Orinoco and Caroni run across vast jungles and savannas, creating rain and powering the Guri dam.

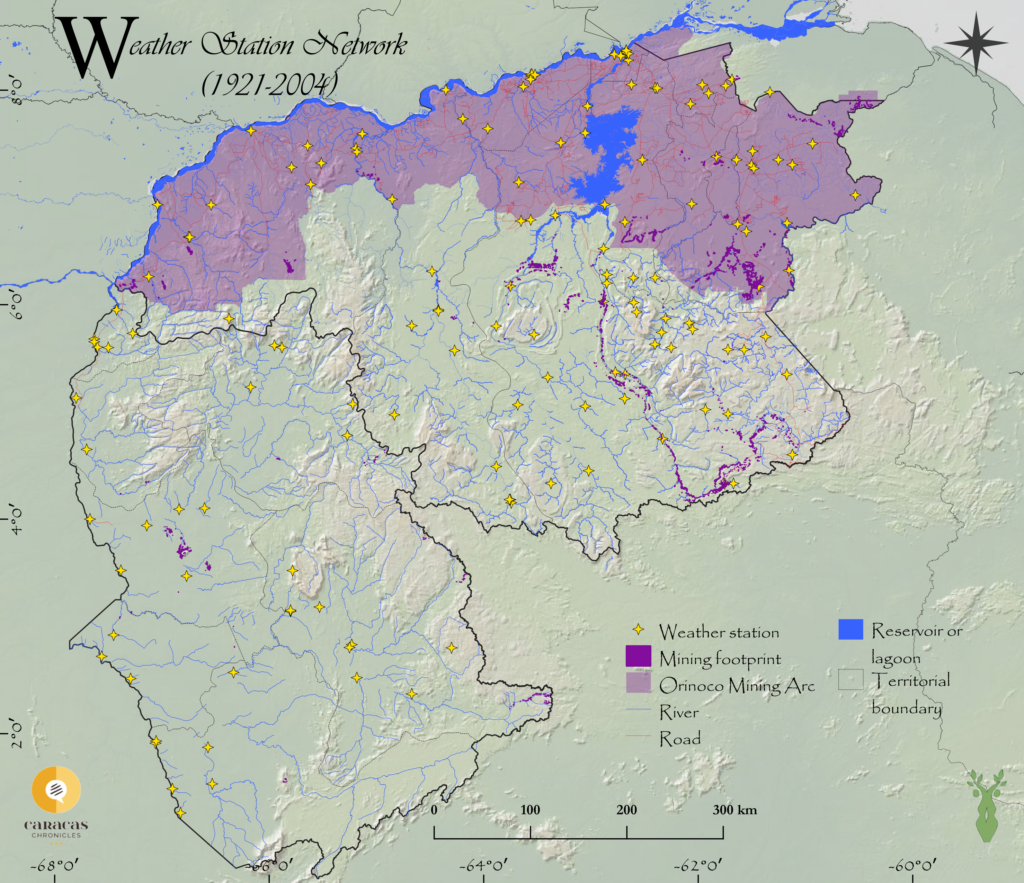

Today, however, those parts are precisely where climate observation is less reliable. Since 2004, weather stations have been dismantled by looters, or abandoned due to a lack of operators, while the whole region has been impacted by mining, deforestation and many forms of trafficking, in many cases at the hands of the state that is supposed to protect it.

Data gathered by the Venezuelan NGO SOS Orinoco shows the proximity of mining sites to places where weather stations were working.

A climatologist from INAMEH, the national weather service currently in charge of the network, said that most of the working stations are in the Caroni River basin, and admitted that the process to replace the old equipment for automated kits reduced data since the year 2000. Before that—in the 20th century—the data bank was more robust. Now, sourcing is, in the best case, intermittent. “With the pandemic in 2020”, said this climatologist, who did not want Caracas Chronicles to publish his or her name, “measurements were interrupted, and vandalism has been constant since then. People think they will become millionaires by selling one of those kits.”

INAMEH issues periodical bulletins based on general satellite data, lacking the detailed information that can only be complete with data coming from weather stations on the field. “The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) allows the use of remote sensors, since maintaining weather stations in inaccessible areas is so difficult,” said the climatologist. INAMEH didn’t respond to our request for a list of operating stations.

In 2016, the French-Venezuelan climatologist Sergio Foghin-Pillin wrote that there was no data on rain in large parts of Guayana, and that only one weather station was operating in Amazonas state, which has 175,000 square kilometers. This lone station in Amazonas, located in San Fernando de Atabapo, was dismantled by November 2023, even if it was located in front of a National Guard post, just by the town’s airport. Local witnesses, who spoke with Caracas Chronicles on the condition of anonymity, said that irregular armed groups that operate drug routes and illegal mining sites are to blame for the trafficking of parts after looting the weather stations.

INAMEH invested in restoring a few stations by the end of 2023 in Amazonas state, and relocated the San Fernando de Atabapo structure in the patio of a house. The institute also restarted a weather station in San Carlos de Rio Negro, which was installed inside a National Guard barrack. Before that, we were deprived of climate data about one of Venezuela’s most important river basins, the one that links the Orinoco basin with the Amazon basin and gives the country access to the Amazon Cooperation Treaty.

According to the database of the Information System for Territorial Management, SIGOT, there’s a weather station, protected by the armed forces, in Puerto Paez, Amazonas state, close to the Colombian border. But during two visits to the site in November 2023 and June 2024, military officers denied such a station existed. And this is a place where climate data would be very valuable: great rivers like Meta, Arauca, Apure, Capanaparo and Cinaruco discharge their waters into the Orinoco, impacting rain, temperature, wind and humidity in the entire basin.

In the main cities of Bolívar and Amazonas states, however, weather monitoring is more constant. The stations in Puerto Ayacucho, Caicara del Orinoco, Ciudad Bolívar and Ciudad Guayana are less vulnerable to looting, and measurements of depth and volume of flow at the Orinoco and Caroní rivers are frequent. The most important thing is that INAMEH technicians are competent professionals, who try to do their best at an official body where talking out loud is forbidden and bad decisions are out of their reach.

This is the shorter version of a feature story produced with the support of Red de Periodistas de la Amazonía Venezolana and Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB), coordinated by the program Incubadora de Historias Amazónicas.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate