“Knock Knock:” The Cyber Repressive Machinery of the Venezuelan Government, Exposed

After the July 28 elections in Venezuela, state actors used Telegram channels and other social networks to pursue and reveal the personal information of opponents of Nicolás Maduro

This article was originally published by Cazadores de Fake News in Spanish. The names of some sources have been changed to protect their identity.

“They’re looking for you!” You have to leave the country!” The first alert messages arrived on Raúl’s phone on July 31, 2024, three days after the National Electoral Council (CNE) of Venezuela proclaimed the re-election of Nicolás Maduro. “I became very paranoid, to the point that I had to throw away my phone. I had the feeling that someone was listening to my calls,” Raúl later told this team.

He did not participate in the post-electoral protests, but was a citizen observing the tallies collection at his voting center. He ended up imprisoned after being the victim of a digital harassment campaign linked to members of the Venezuelan government. His photograph, name and identification document number appeared along with the information of other men and women in his town, in an image where it reads in large: “WANTED.” They were designated as “guarimbero leaders,” a term used by the Maduro government to refer to opposition protesters. He also appeared in an image of a WhatsApp group of members of the ruling Venezuelan United Socialist Party (PSUV) in his community, called “Compañeros Psuv”, and in an anonymous account on Instagram, where he was described as a “terrorist”.

Like Raúl, dozens of young people, political leaders, social and community leaders, electoral observers or protesters, have been publicly exposed on social media.

This investigative alliance managed to identify twelve cases like Raúl’s. Their data was disseminated on social media profiles linked to the Venezuelan ruling party; they are political activists or they went out to protest after the announcement of the election result; and they ended up in a detention center while the regime carried out “Operation Knock Knock”, as the Madurismo has called the widespread campaign of arrests that according to international human rights organizations are arbitrary. Another 16 citizens remain protected and two are exiled.

“I don’t want to leave the country, I have my life here and I want to continue doing political life (…) Why me? … I’m not a criminal,” Raúl wonders.

Operation Knock Knock was not a spontaneous initiative among followers of the ruling party. On the contrary, it involved interaction between state actors and collective efforts at doxing, the technical term for the dissemination of someone’s personal data online without their consent.

For Marino Alvarado, coordinator of human rights organization Provea, Operation Knock Knock is a “State terrorism policy” where any allegedly suspicious person “is at the mercy of the whim and arbitrariness of any police body.”

This journalistic investigation compiles traces and reconstructs events recorded online starting on July 28, from when 1,824 arrests have been recorded until October 25, including 69 minors, according to the organization Foro Penal, which provides legal assistance to detained people. arbitrarily and to their families.

This investigation is the result of Los Ilusionistas, a project coordinated by the Latin American Center for Journalistic Research (CLIP), in which reporters and digital researchers from 15 media outlets and organizations in Latin America collaboratively investigate the circulation of false information and the manipulation of the public conversation in digital media, during this “super electoral year” of 2024 in Latin America.

Identify and isolate the “enemy”

Doxing cases by state:

“I need you to search #telegram for the #CazaGuarimbas group and report it. “They are hunting those who come out to demonstrate. URGENT!!!!” Complaints like this began to go viral on social media in Venezuela since July 30, while pro-government civil groups were seen in the streets, armed, terrorizing people and dispersing public events with gunshots.

The Telegram channel @CazaGuarimbas was promoted among digital spaces of followers of the Venezuelan government, exposing opponents behind the slogan: “NO TO FASCISM. NO TO VIOLENCE.” And although, as we demonstrate here in detail later, @CazaGuarimbas, now deleted, was the first but not the only channel created to “hunt” dissident voices.

According to the analysis of this alliance, Telegram, the instant messaging application of Russian origin, is one of the main platforms from which this persecution campaign was articulated and featured the largest number of actors promoting it.

A follow-up to the timestamps that each publication leaves revealed that @CazaGuarimbas was the first group on Telegram in which personal information of people who participated in the protests against Maduro was shared, in an organized and systematic way, being the heart of the doxing campaign, which lasted for several weeks.

The first publication on @CazaGuarimbas was made on July 30, 2024 at 01:11 a.m. Venezuela time and, in just seconds, it was forwarded by one of its administrators to @CpnbDaet, the official Telegram channel of the Directorate of Strategic and Tactical Actions (DAET) of the Bolivarian National Police Corps (CPNB).

Between July 30 and 31, 86 messages from @CazaGuarimbas were forwarded to @CpnbDaet, which highlights the coordination between both channels and suggests that @CazaGuarimbas functioned as a kind of “auxiliary” channel where the DAET was centralizing accusations.

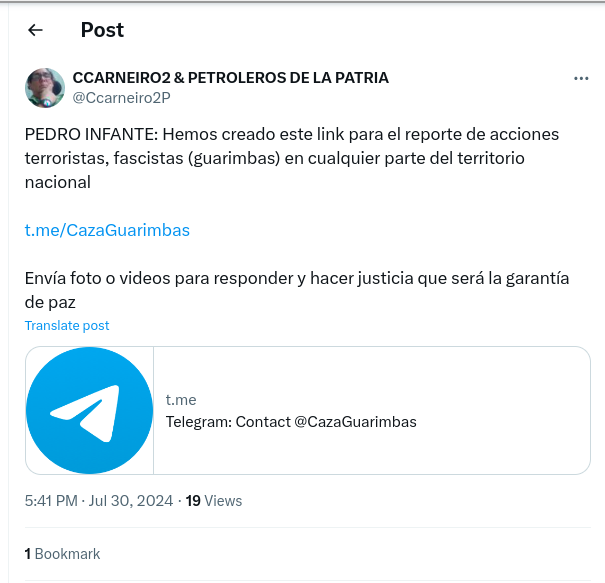

At 10:43 a.m., the link to the Telegram channel @CazaGuarimbas was published in the CC200 mobile application, an internal online electoral organization system of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV). Various accounts on social media documented, with screenshots, that this link had been shared on the internal communication channel of Nicolás Maduro’s “Venezuela Nuestra” Campaign Command, in CC200.

“We have created this link to report terrorist, fascist actions (guarimbas) in any part of the national territory,” said the message published in the app, followed by the link to the channel @CazaGuarimbas, which also requested members to send photos or videos.

The message reached thousands of PSUV militants and members of its organizational structures throughout the country and, in a couple of days, the Telegram channel added more than 21,000 followers.

@CazaGuarimbas administrators shared links to two new backup channels: @ContraLasGuarimbas and @CazaGuarimbasVe, where they began sharing forwarded content from the original channel. The official DAET channel, @CpnbDaet, associated a discussion group with the channel, called @SeBuscan, which continued to receive reports about protesters in the streets, as had been done with @CazaGuarimbas. The channel and the group, both linked to the substructure of the Bolivarian National Police, share the same administrator. Some of its users are police officers according to the descriptions in their profiles.

“I know where one of the guarimberos lives in Mérida (…) Last night he was burning rubber (tires).” A few hours after the creation of the @SeBuscan group, users began to activate. “Comrades, be specific,” wrote the administrator of said group at 10:43 that day. He then clarified the way in which the information is received. “Write in a single message: complaint, place and photograph.” While group member users sent their reports, the @SeBuscan administrator did the same, forwarding content from @CpnbDaet and vice versa. Always a photograph. In some cases, a video. Full names, family members or places of work. Where they live and even phone numbers are some of the personal data revealed in these chats. On several occasions, the victims are very young, at least in appearance, teenagers.

At 8:30 p.m. July 30, official Government accounts on Instagram, Facebook and Threads shared links to the @SeBuscan group. “Citizen security organizations ask for the support of citizens to identify the men and women responsible for extreme violence. If you know someone who is violent, you can send it through this platform,” says one of the government publications.

“After two months of being in hiding, I can tell you about the situation that has been happening to me,” says journalist Luis Gonzalo Pérez, from the communications team of opposition leader María Corina Machado and presidential candidate Edmundo González, on Instagram. Exile, he says, was not something he expected, but he ultimately deemed it necessary to safeguard his family.

As of July 28, he began to receive threats from state security agencies. He also received messages alerting him to his personal data circulating on the internet. As if he were a criminal, Luis’s photograph was sent along with a reward notice on the DAET’s Telegram channel, where they accused him of “paying minors and selling drugs to motorists”, supposedly present in the demonstrations rejecting Maduro’s re-election.

Terror campaign

Other corners of the internet began to fill with doxing activities originally spread via Telegram. This team found hundreds of pieces of content of this type published on other high-reach platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, Instagram and X.

Parallel to the collaborative doxing, and especially on TikTok, another stage of the plan was beginning to take shape: a rebranding strategy of “Operation Tun Tun”, which dates back to the repression of protests in 2017. Diosdado Cabello announced it with great fanfare on his well-known television program “Con El Mazo Dando”, which for a decade has been the propaganda arm of the government.From Provea, Marino Alvarado also remembers the efforts by Chávez to turn citizens into informers when the Military Intelligence and Counterintelligence Law, known as the “Ley Sapo”, was approved in 2009. “This law established that all people should be confidants of intelligence agencies. It was intensely denounced by human rights organizations and by some personalities from Chavismo, including José Vicente Rangel,” he points out. But what happened the week after July 28 was a “more blatant” and, now, “more coordinated promotion of sapeo” impulse, says Alvarado.

@dcdo_cojedes Operación TUN TUN SIN LLORADERA!! gracias por el vídeo @MusicaYAlgodeArt47 ♬ sonido original – DCDO_COJEDES

ikTok allows you to see how many times a sound has been reused in other publications, so when you click on the terrifying audio, dozens of videos from other users appear that advertise “Operation Tun Tun”, while also generating doxing .

For this research, more than 30 similar accounts were identified and analyzed on TikTok. All of them show associated behavior, not only through images, languages and music, but also through their monitoring relationships. Profiles associated with “Con El Mazo Dando” (@mazo4f and @conelmazodandotv), along with a myriad of police accounts, are some of the most interconnected nodes. These become visible as larger bubbles when carrying out a network analysis with the help of the Gephi and Flourish visualization tools.

Another segment is a group of more isolated accounts, dedicated to pro-government propaganda, most with revolutionary symbols in their profile photos, republishing videos of statements by senior officials, news pieces and pro-government virals, among others. From time to time, these accounts also doxing, primarily by sharing images of people who have been detained in “Operation Tun Tun.”

Recycled content from Telegram was also leaked to Facebook. The “Se Busca” images and stigmatizing videos were shared mainly by personal accounts, political groups and community participation instances such as the Communal Councils and the Hugo Chávez Battle Units (UBch).

On Instagram the content was more ephemeral due to the rapid reporting efforts by other users. Even so, there are still traces of the dissemination of intimidating content in official DAET accounts and in the profiles of personalities such as the director of the Corps of Scientific Criminal and Criminalistic Investigations (Cicpc) and the vice minister of the Integrated Police System and its main colonel.

For this analysis, 101 accounts and nearly 400 publications distributed between Telegram, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram and X were stored. A quantitative analysis of the language shows that two of the most used word bigrams are “Se Busca” (63 mentions) and “Tun Tun” (44). The trigrams “in the state” (33) and “are sought in” (23) account for the obsession of these accounts with the geographical location of the victims. “Guarimbas” (33), “guarimberos” (23), “terrorism” (20), “terrorists” (17), “criminal” (18) “vandalism” (15), “road closure” (10) , “incitement to hate” (18) and “hate crime” (9) appear as the most frequent accusations.

In its latest report on Venezuela, the United Nations Verification Mission documented, after the election, state behavior that constitutes “crimes against humanity”, including extrajudicial executions, torture and arbitrary detentions as part of a “generalized and systematically against the civilian population, in compliance with a state policy of silencing, discouraging and suffocating the opposition.”

In this context, cyberactivism manifests itself in different ways on social networks. From children who protest in the popular online game Roblox, to TikTok users who share eccentric recipes with products from the Supply Committees.

The opposition also doxed

This team also found and stored doxing content directed at public officials, their relatives or people linked to government figures, the so-called “enchufados”

“Through WhatsApp they are threatening the Venezuelan military family, all officers, the police family, street and community leaders. They are threatening anyone who does not speak out in favor of fascism,” said Nicolás Maduro at a public event on August 6. Immediately afterwards, the president began a campaign among public officials to eliminate the platform from their devices. The day before, he had attacked Instagram and TikTok in a televised address, calling them “conscious multiplier instruments of hatred and fascism.”

His public fight with the CEO of X, Elon Musk, ended in the blocking of the social network on August 8. X functioned as one of the main channels of information and freedom of expression for Venezuelan citizens, denouncing organizations such as Venezuela Sin Filtro. Although the restriction would be lifted after 10 days, as of the date of publication of this report, the platform continues to be blocked by the country’s main Internet servers.

In parallel, Maduro was trying to position VenApp, his reporting management application on public services, which the journalistic investigation published in 2023, Mercenarios Digitales, had already denounced for its use for electoral purposes. This app shares creators with the aforementioned CC200. The creation of both is linked to a group of companies that revolve around Venqis, a Panamanian political communication company directed by Brazilian consultant André Golabek Sánchez. Both applications were available in the Google and Apple application stores, under the developer profiles “Nolatech, S.A.”, “Tech and People, SRL” and “Cyber Capital Partners Corp”, all names of companies registered in Panama or the Republic Dominican and linked to Golabek Sánchez.

Although VenApp was initially presented as an electronic government application, screenshots of its first versions revealed an early electoral purpose, including buttons such as “National 1×10 Activist”, referring to one of the PSUV’s mobilization strategies during electoral processes. Shortly after, that section disappeared from VenApp and CC200 emerged, another application whose installation and use was promoted in the PSUV militancy. CC200 would manage the “1×10” in electoral processes and through it private messages could be sent to the members of the ruling party.

Meanwhile, VenApp continued to be used openly to receive public service reports, until it was exploited as a digital reporting tool. On July 30, he announced in a public event the creation of a new section in VenApp for citizens to report “those who have attacked the people, to go after them.”

Users on social networks recorded the changes to the application on their phones and uploaded screenshots. But Maduro’s dream only lasted one day.

Legions of cyberactivists organized to denounce the VenApp application en masse, a call even made through the Community Notes on X. And it worked. The next day, VenApp was already out of the Apple App Store and Google Play.

While all this was happening, the Telegram channels analyzed for this investigation continued to operate at full speed.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate