How the End of Apartheid Created Danny Ocean

In his new album, Venequia, the Venezuelan pop star mixes reggaeton and protest in a personal reflection on political conflict and exile. This is the story behind the artist and his hits

Months after a couple of visits to Venezuela, his first in years, Venezuelan singer-songwriter Danny Ocean (b. 1992) decided to write a new song. “Maybe we shouldn’t have seen each other again, maybe I shouldn’t have taken that flight, you told me you changed again, but you only dyed your hair,” he says in ‘Por siempre y para siempre’, from his album Venequia (2024), released shortly before the July 28 elections and alluding to the Venezuelan political conflict. “I want to tell you everything I’ve lived, the crazy adventure it’s been since we released that song ages ago, everyone asks me what happened to you.”

For his fans, this last line was a reference to “Me Rehúso,” the hit about a couple separated by Venezuelan emigration that launched him to fame in 2017. But “Por siempre y para siempre” was not actually referring to the doomed love of “Me Rehúso.” Instead, Ocean –whose real name is Daniel Alejandro Morales Reyes– explains, in a forum at Harvard University’s Kennedy School after his concert in Boston, that the song expressed what he had felt upon returning to Venezuela. Although he brought his instruments, although he was in his room before he migrated to Miami and then to Mexico, although he sat at the Mirador de Valle Arriba looking for inspiration in the Ávila mountain, he was unable to make music. “I didn’t connect,” he says. “I felt like a tourist in my own country.”

Inspiration came within months. According to Ocean, “Por siempre y para siempre” is the “most special” song on the album: Its cover is a textless image of the broken tiles on the floor of Maiquetía and includes hits like “Por la Pequeña Venecia” –in which he sings to the Venezuelan government in a language that shows it as an individualized emotional abuser– or “Escala en Panamá”, a hit that skyrocketed due to the pre-electoral frenzy. The music video, which shows crowds of Venezuelan migrants desperately returning to Venezuela, culminates with María Corina Machado’s voice in the form of an airport announcement: “Welcome to Venezuela, welcome home.”

Ocean, in fact, is a kind of reference for the Venezuelan exile. Since 2019, he has been collaborating with UNHCR –the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees– and has both sung at its ceremonies and visited some camps. Ocean, he explains, came to UNHCR through the Nigerian girlfriend of one of his friends who was enchanted by “Me Rehúso”.

His songs also constantly allude to “Babylon boys” and “Babylon girls” –an invention of Ocean that has taken on a life of its own since it occurred to him while playing music with his friends at home in Caracas. “That’s cool,” he told them about the term Babylon girl , a union of two words whose meaning would come later. Recently, for example, Ocean tweeted an image of the Babylonian exile from the Bible alongside another of Venezuelan migrants crossing the Andes. Today he even finds something mystical in the phrase, saying: “I feel that God and the universe is a woman,” he explains. “It’s giving thanks to that muse.”

It’s part of his authenticity that permeates even his stage name: Ocean used to graffiti in Caracas and used “Daniel O-C-T” as an alias, alluding to the hip-hop scene that existed in the country. Until one day, in Miami Beach, a friend gave him a nickname: “Danny O.” Ocean liked it. He saw the waves of the sea, thought of George Clooney’s rizz in Ocean 11, and became Danny Ocean: the name that, little did he know, he would bear as a Latin American star.

From Mandela to Venequia

But long before he was Danny Ocean, Daniel was the son of a Venezuelan diplomat from the democratic period. He spent his early childhood in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and six years in Namibia, recently independent from apartheid South Africa. There, the singer says, the rise of Nelson Mandela –who was serving as president in South Africa and carrying out the dismantling of apartheid and was quite popular in Namibia– influenced him, as well as his mother’s culture-oriented upbringing style. In his album Venequia, “a pain that I feel very personally” explains Ocean, he touches on the gray areas of a democratic transition in a pop way: “I’ll exchange you justice for peace, yes, let’s play dumb for the Little Venice,” he says in one of the songs on the album, “Just go away now, please.”

More than ten years after Namibia, Ocean –following the student protests of 2014– headed to Miami and obtained political asylum. His direction was not very clear; he initially hoped to move to Panama. So, he decided to write a song as a Valentine’s Day gift –lacking money for a gift, he says– for the girlfriend he had left in Venezuela. So, he uploaded “Me Rehúso” on his YouTube account, where 200 or 300 views were a success. But the song began to have hundreds more views. And then thousands. “It exploded and splashed everywhere,” says Ocean, who did not have any fanbase nor had he tried to play in bars or music circuits before. On Spotify alone, “Me Rehúso” –it broke a record by becoming the Latin song with the most weeks on Spotify’s Top 50 Global list, with more than 36 weeks— today has more than a billion streams. In fact, at least until 2021, it is the most listened-to song of the last decade on Spotify in Latin America.

“It changed my life, like winning the lottery,” he says. He was now signed to a record label and even had a work visa. “I wasn’t ready for an interview; I hadn’t gotten on a stage.”

For Ocean, the song –which revolves around the promise of a kiss when he reunites with the love he left behind– exemplifies a kind of philosophy of his own: “I like to give the problem and then give it hope with a possible solution,” he explains. But “Me Rehúso” also resonated with a generation affected by political conflict and the resulting migration. “I come from a generation in which many artists were talking” about the political issue, he explains, referring especially to Venezuelan hip-hop from a decade ago.

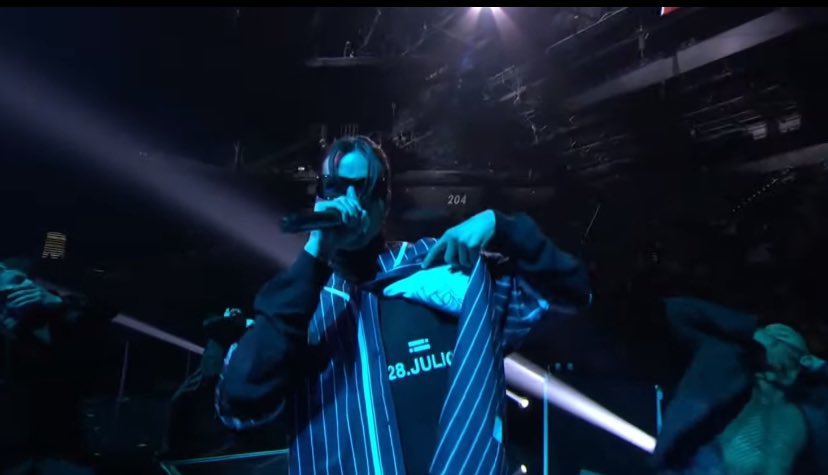

Still, the singer believes that “it is not fair to demand that artists have a position.” For Ocean, many artists only seek to create art, make money, or become famous. Not to influence politically or participate in social movements, to the point that María Corina Machado makes a cameo in one of your songs or you show the elections’ date at your Latin American Music Awards performance in Las Vegas. In addition, Ocean –who does not do concerts in Venezuela as a kind of protest, transforming him so far into a performance exclusive to the diaspora– says that many artists of “the Venezuelan scene” are threatened through social media, fear for their families or even have their passports annulled.

Although he believes that in the Venezuelan music scene there is now “a beautiful moment in which we are all intertwined, together,” citing as an example “Veneka” –the new song by Rawayana and Akapellah– as one that “promotes [Venezuelan] culture outwards,” Ocean considers that there are many challenges for the Venezuelan music industry: from the dispersion of talent due to migration to the lack of “an economic opening” that he considers necessary.

Ocean refuses to define what democracy is for him. But, he says through tears, “I live in Mexico and sometimes I want to have a beer with my friends, with my brothers… [and I can’t because of the separation from exile], this is not right.” Not being able to vent on occasions like other Latin Americans do when they have their families and friends by their sides, he explains, “is not cool.” For him, these impossibilities show a moral dimension of the consequences of the crisis: “It sucks not being able to grow professionally, personally,” says Ocean about the country, “Everything is so broken.” But Venezuela, he assures when asked about his next artistic steps, will be por siempre y para siempre in his songs.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate