Madurismo’s Most Dangerous Job Claims Another Victim

At a moment of dynastic consolidation, Maduro resorts to a power move against former oil chief Pedro Tellechea. Others before him fell from grace in different circumstances

On July 22, just five days before the presidential election, Colonel Pedro Tellechea Ruiz inaugurated the Nicolás Maduro Moros Audit Room as part of a “zero corruption” plan at the state oil company. PDVSA’s communications, voiced by fiscal audit director Didalco Bolívar Rivas, portrayed Tellechea as the man responsible for running the oil industry with transparency and efficiency, replacing corruption with progress.

By October 21, only hours after the government confirmed Tellechea’s arrest, the state’s narrative about PDVSA’s “star manager” took a sharp turn. Without naming the colonel, Maduro referred to the ongoing purge, which, according to El País, already included 12 detainees.

“I will not rest my arm or soul in the fight against corruption,” Maduro said on television, paraphrasing national hero Simón Bolívar. “We are at war against bureaucracy, corruption, and betrayal.”

“This revolution has had to investigate people who have been a part of it,” Diosdado Cabello said today. “At this point, there can be no innocents. Tellechea put the stability of the oil industry at risk.”

Initially, the Public Prosecutor’s Office didn’t frame Pedro Tellechea’s arrest as part of an anti-corruption offensive, like those that ousted Tareck El Aissami and his allies or Rafael Ramírez, Eulogio del Pino, and Nelson Martínez before him. In just two months, Tellechea went from being demoted to Minister of Industries and National Production, to resigning from this new role due to “health problems,” and, days later, being accused of handing over PDVSA’s automated command to a company linked to U.S. intelligence.

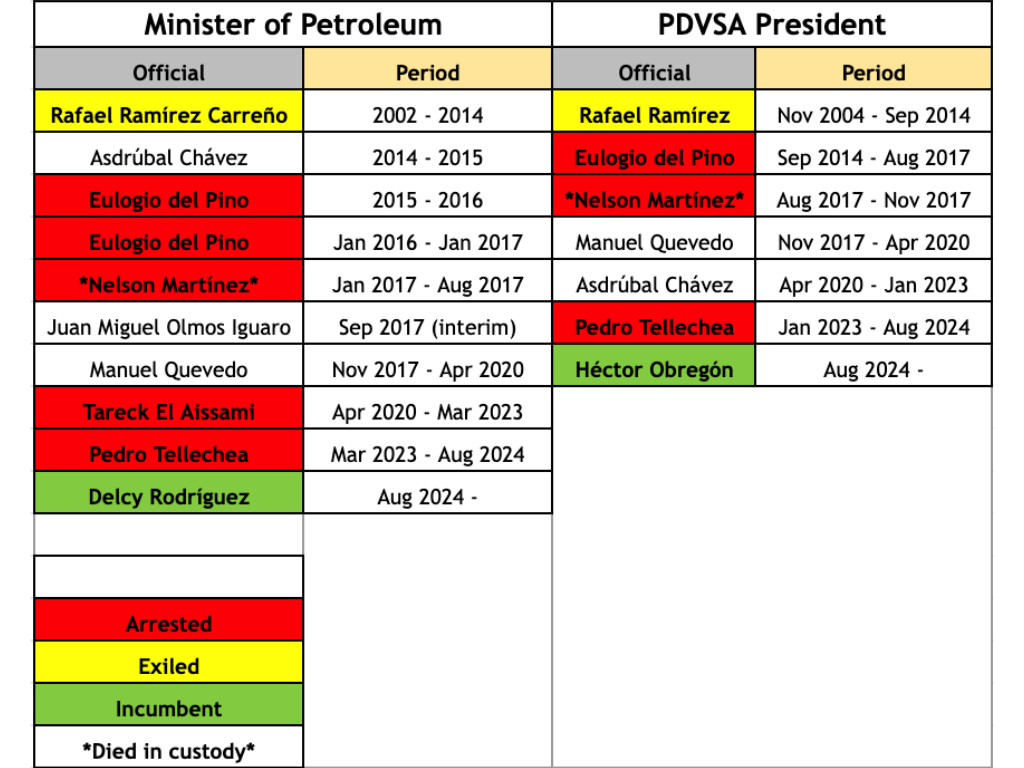

This shakeup within the chavista elite mirrors more closely the removal and arrest of Eulogio del Pino and Nelson Martínez in 2017 than the hunts against Rafael Ramírez or Tareck El Aissami. Yes, four of Tellechea’s predecessors fell from the highest echelons of Madurismo.

We don’t know what compromising material the chavista leadership might have on the colonel, if any at all. What we do know is that, before ascending to the top position, he was trusted with other key companies: the aluminum producer CVG Venalum, the petrochemical firm Pequiven, and Metor, a methanol producer jointly owned with Mitsubishi. He also oversaw Monómeros, Pequiven’s Colombian subsidiary. His tenure in these basic industries didn’t seem salient, but in January 2023, he was appointed Minister of Petroleum and tasked with auditing Tareck El Aissami’s management of PDVSA—his “lifelong brother” and military academy peer.

After the election fraud and post-election repression, Tellechea’s downfall seems to coincide with a realignment within the chavista regime, where Maduro is appeasing key members of his inner circle and high-ranking security officials. Delcy Rodríguez is already running PDVSA—via the Ministry of Petroleum—while retaining her position as Vice President. Diosdado Cabello has taken over the Ministry of the Interior after more than a decade out of government. His cousin, former Army commander, now heads SEBIN, the regime’s intelligence agency. Vladimir Padrino and Domingo Hernández Lares, the Defense Minister and the head of the Armed Forces’ strategic command, have both been reaffirmed. Johan Hernández Lares, Domingo’s brother and former military chief of the Capital Region, now commands the Army. Meanwhile, the brother of Alexander Granko Arteaga, a military intelligence chief linked to crimes against humanity, now controls the issuing body for license plates and driver’s licenses.

Tellechea—who, according to his LinkedIn profile, studied naval operations and public finance—was the figure Maduro used to present a more diligent and serious PDVSA to the United States, as it became necessary to engage with Western oil companies again.

Right after Chevron’s license was issued, Tellechea’s first move was to suspend oil trade and review PDVSA’s invoices from 2020-2023, when El Aissami was responsible for bypassing financial sanctions on PDVSA and ensuring crude reached refineries in the East through partners like China, India, Turkey, and Iran.

Tellechea’s new administration revealed that PDVSA had not collected over 80% of the value of its exports. This led to El Aissami’s purge—a former vice president sanctioned for drug trafficking—and the removal of around 80 collaborators, placing Tellechea firmly in control of the industry. His leadership saw the return of some Western oil companies to Venezuela under the Barbados Agreement, a reduction in public debt, and a roughly 25% increase in production compared to 2022.

Shakeup in PDVSA amidst times of rage

Maduro is navigating the complete collapse of his legitimacy after having to suppress dissent and, perhaps more than ever, lay bare the repressive nature of his regime. Speculating on specific winners and losers here would be risky. However, like in 2017, Maduro seems to be rewarding figures who represent critical support at this moment, signaling that anyone, no matter their reputation, is expendable when survival is at stake.

This shakeup within the chavista elite mirrors more closely the removal and arrest of Eulogio del Pino and Nelson Martínez in 2017 than the hunts against Rafael Ramírez or Tareck El Aissami. Yes, four of Tellechea’s predecessors fell from the highest echelons of Madurismo.

Eulogio del Pino took over PDVSA in September 2014, following a period of industrial collapse and unprecedented looting in modern history. With extensive experience in the company and a master’s in engineering from Stanford University, Del Pino had to manage amid deep debt, plummeting production, and the proliferation of missions and international alliances financed by petrodollars. He didn’t reverse the decline, but that doesn’t seem to be the central reason for his downfall. Production continued to fall when, in March 2017, the Maduro–controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice assumed the powers of the National Assembly to override his opponents—including regarding the creation or modification of joint ventures, a responsibility that constitutionally belongs to the legislative branch, then controlled by the opposition. The National Guard and National Police played leading roles in a traumatic protest cycle that left 43 dead and 3,700 detained, with Maduro more willing than ever to concentrate power and empower those who kept him afloat.

That August, with the Constituent Assembly in place and 50 PDVSA officials already arrested, Del Pino was removed. He was briefly succeeded by Nelson Martínez—a career PDVSA official, chemical engineer, and former president of CITGO—who had been working alongside him from the Ministry of Petroleum all year. Manuel Quevedo, a National Guard general with no experience in anything remotely similar to PDVSA, was appointed to both positions in the company and the ministry. Three months later, Del Pino and Martínez were imprisoned. Nelson Martínez died in custody in December 2018, a year after his arrest. Chief Prosecutor Tarek William Saab accused them of the disappearance of $500 million in crude oil and irregularities in one of the most opaque joint ventures of the chavista era.

In May 2017, with the opposition on the streets and serving as Venezuela’s ambassador to the UN, Rafael Ramírez wrote about the dangers of depoliticizing PDVSA and accused the government of “dismantling the defense mechanisms” of the Bolivarian Revolution. His criticisms of Maduro escalated after he resigned as ambassador, ultimately becoming one of the main dissident chavista enemies of madurismo, alongside other former allies like outcast prosecutor Luisa Ortega Díaz, General Miguel Rodríguez Torres, and former minister Andrés Izarra. The opposition accused Ramírez of diverting $11 billion during his 12-year leadership of the oil industry—when 15 state assistance programs were funded, and he and Chávez managed a National Development Fund worth $140 billion, according to Transparency Venezuela.

Now, Colombian businessman Alex Saab—exchanged last year in a prisoner swap with the United States—will take over Tellechea’s role as Minister of Industries. Delcy Rodríguez had already recently taken over the Ministry of Petroleum, and Héctor Obregón—who was executive vice president during Tellechea’s term—is now leading PDVSA. Among Delcy’s objectives, considered by some businessmen to be the most “capable” and “palatable” figure within the chavista elite, is surpassing the one-million-barrel-per-day mark, with a more totalitarian Maduro and with a question mark above U.S. sanctions policy. She will have to navigate this in the state’s most dangerous post, where recognition and disgrace often come without warning. Good luck, Delcy!

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate