After Venezuela's Credit Crunch, Cashea, a BNPL App, Is Booming

This service is enabling five million Venezuelans to buy now and pay later, fueling consumption across the country

Ever since he saw yellow-clad Cashea promoters in the Tolón shopping mall in east Caracas, Luis Calatayud –a 25-year-old psychologist who lives in Caracas– has been using the app to buy things in the city: a Venezuelan Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) fintech app that allows consumers to make purchases and pay for them in installments with no interest. The app currently allows users to shop in 5,000 stores throughout the country and its makers hope to add 4,000 more before the year ends. In fact, according to CEO Pedro Valenilla, around 20,000 to 25,000 stores belonging to 15,000 companies are on the waitlist to join the app.

Per company estimates, around 1% of the Venezuelan GDP passes through Cashea and its user base surpasses 5 million users – or the equivalent of around the entire population of Costa Rica.

“If something costs $200 dollars and I have the $200 to pay for it, but I don’t want to spend the whole $200, I pay $100 and I keep $100 as cash flow”, Calatayud says. “Then, when I receive more money, I use it and pay my installments. The whole thing is very convenient.” One time, he recalls, he went to buy something and realized he didn’t have enough money in his wallet: “Cashea saved me”, he says, “I didn’t have to leave my purchase at the cashier.”

For him, Cashea has not only allowed young professionals like himself to have a higher purchasing power, but also to acquire the material assets their careers need. “Now you can pay for very expensive things in six, nine or even twelve installments, which I think I’m going to use to buy a new phone”, he says. “I already used Cashea to buy a tablet that I needed for work. When I moved out by myself, I bought through Cashea many of the things [for my apartment] in the EPA store.”

Per company estimates, around 1% of the Venezuelan GDP passes through Cashea and its user base surpasses 5 million users – or the equivalent of around the entire population of Costa Rica.

Through consumers like Calatayud, Cashea has rapidly grown in Venezuela and surpassed its executives’ original expectations. “We thought at one point that we could lose up to five or six dollars for every 100 dollars that passed through Cashea”, CEO Pedro Vallenilla says. “Then we really thought we would start losing three dollars… then less than one.” According to Vallenilla, these very low default rates are “best-in-class numbers” when compared to regional rates. The country has a long tradition of bank access, which puts it in the second place in the region. “Venezuelans are among the best payers in Latin America”, Vallenilla says. “There is a perfect correlation between the quality of the credit product and the default.” As people perceive their gains and access through Cashea as high, they care for their accounts and debts. While Cashea only expels you permanently if you commit fraud, the company charges a $4 fee for every unpaid installment to allow you to keep using the app.

Calatayud, for example, has gone up through the different purchasing-levels the app allows. “You say: ‘damn, you have the ease to receive the product immediately after you make the first payment’ and that also makes you try hard to have your payments up to date”, he says, “because at the end of the day the application trusted you and you trust it. The issue of trust really is very, very big.”

Venezuela’s credit crisis

In fact, Cashea’s high appraisal by Venezuelans is also the result of the country’s lack of consumer credit. Its BNPL offering appears following the country’s credit crash after a decade-long recession and the hyperinflation crisis. “Venezuela reached a point where credit fell from levels of almost sixteen billion dollars in 2014 to two hundred million dollars in 2021, a historic low”, says Asdrúbal Oliveros, director of consulting and research firm Ecoanalítica. “This pulverized not only credit for companies but also consumer credit.”

While credit has recovered since then to two billion dollars, this is mostly focused on companies and is quite insufficient. “There are still important needs for the Venezuelan population”, Oliveros says. “The financing needs for personal credit is around one billion dollars and banks are not even handling 20% of that.” According to Oliveros, the country’s credit portafolio –for the economy’s current size– should be around fifteen billion dollars: twelve for companies, under normal conditions, and three for individuals.

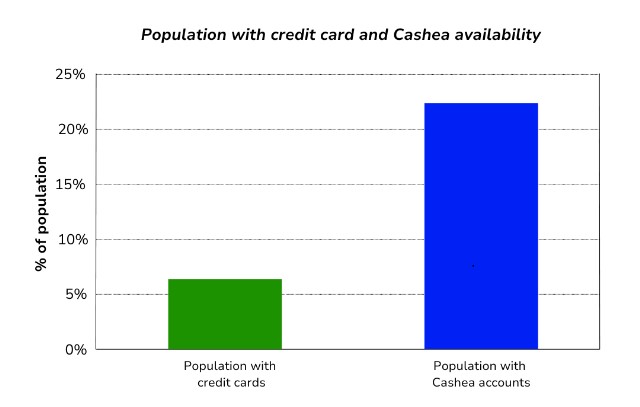

Thus, in credit-strapped Venezuela, Ecoanalítica estimates that only 7% of the population has credit cards while over 20% has a Cashea account. In fact, the firm estimates that during 2023 –when the Venezuelan economy saw a slowdown– stores in the Caracas Metropolitan Area saw a -3,3% growth contraction. Meanwhile, stores that offer Cashea saw a 30% consumer conversion rate. “If you as a store offer financing options, in this case Cashea, it is obvious that the number of buyers increases”, Oliveros says. “It is giving an additional option beyond the day-to-day. Credit helps consumption and sales and that is unfortunately insufficient in Venezuela today.”

The lack of credit has propelled Cashea as an alternative throughout the country. From Caracas, it started operations in Barquisimeto, Maracaibo, and Puerto La Cruz. Then, it jumped to Valencia. By May this year, Cashea was already operating in 12 cities and, after reaching the city of Mérida, it is now covering 15 cities –including Acarigua, Cumaná and Valle La Pascua. The startup expects to expand soon to El Vigía, a small Andean city with less than 170,000 people.

Cashea has skyrocketed to become Venezuela’s most downloaded app both on the Google Store and the Apple Store, reigning over social media apps like Instagram and TikTok.

The rise of Cashea

But Cashea didn’t begin as a giant.

Vallenilla believes the app is “the outcome of experiences that have marked my life”: first, his string as founder and board member of TuDescuentón, a former Venezuelan digital coupon platform. Then, following the pandemic, Vallenilla was “forced to take the first job that was offered to me” and ended up working in consumer debt collection agency Colektia. “It was an industry that I didn’t know anything about and ended up falling in love with it”, he says. “We managed 3,8 billion dollars of consumer credit for Nubank, for Santander, for Itaú, for Falabella” in Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

As Vallenilla’s previous experience with consumer apps mixed with his newfound love for consumer credit, things started to move in his home country: “the dollar began to play aggressively in Venezuela, even as legal tender”, he says, “Then [delivery startup] Yummy did what it did: for the first time, a Venezuelan company raised venture capital.” For Vallenilla, Yummy’s “disrupting” rise around 2021 was “the before and after of startups in Venezuela. They opened the door for companies like Cashea to exist today.”

Vallenilla decided to leave Colektia and join Cashea’s funding team with Ramón Lange, now the company’s COO, who had worked in regional delivery company Rappi for five years and had been exposed to Latin American markets; Argentine-Venezuelan software-savvy tech entrepreneur and now Cashea CTO Nicolás Curat, and Ivy League graduate and former McKinsey manager Arnoldo Gabaldón – the startup’s CFO. And so, with a small budget, Cashea officially began on October 3rd, 2022.

Despite the economic liberalization that allowed for startups like Yummy and Cashea to thrive, the company’s C-suite still had to sail through Venezuela’s labyrinthic regulations. “We were not going to launch Cashea until it could socialize and have the approval of the local regulators”, Vallenilla says. Through the year leading up to the official launch, “we took thousands of documents to explain the business model, so that the regulators [in the Ministry of Finance and SUDEBAN] could understand who was behind the business, what it wanted to do, what the experience was, what our security and information policy was”, Vallenilla says. “After four or five attempts, the regulator understood our model and gave us the approval.”

Trying to build a network effect, the company started with one node, to expand from there. That first node was the Sambil shopping mall in Chacao: a first tryout area, with yellow-clad Cashea promoters. “We said: I’m going to win a shopping mall, then I’m going to win the second shopping mall, then I’m going to win the third shopping mall, and by winning the 20, 50, 60 shopping malls in the country we’re going to win in Venezuela”, he says. The experiment at Sambil was successful. The Tolón and Líder malls followed. And then CCCT.

Cashea has skyrocketed to become Venezuela’s most downloaded app both on the Google Store and the Apple Store, reigning over social media apps like Instagram and TikTok.

Yet, before the Sambil tryout and two weeks before the official launch, Cashea sought first attempts with a few individual shops: Depofit, a sports shop, and optician’s Doctor Lentes – which saw the first commercial transaction. “The day we signed Doctor Lentes, the [store’s] doctor called me and told me a woman named Catherine arrived with her daughter Sofía, and they need glasses but don’t have money to pay them in full, and Sofía can’t go back to school the next day if she doesn’t have the glasses”, Vallenilla says. “What do you think if we do your first transaction?”, the doctor asked. And Sofía became Cashea’s first client. “I said: this was meant to be!”, Vallenilla says. “Today, the first thing people see when they start working with Cashea is Sofía’s story.”

Transnational Cashea?

The company’s growth, like Yummy’s, has since then been funneled by foreign investors. “In our last round [of investment] we have unicorn-founding investors, from venture capital funds from New York, California, Mexico”, Vallenilla says. These include California-based fintech investor NuMundo Ventures, Mexico City-based venture capital firm 99 Startups, unicorn startup Kavak’s Roger Laughlin and Yummy’s Vicente Zavarce’s fund Epakon Capital.

Cashea has recently expanded its scope. While it began focusing on casual purchases, with a 42-days payment deadline and zero interest, it has since expanded to a three-month deadline and has allowed for a wider range of purchases: from supermarkets and pharmacies to motorcycles. Working mothers who haven’t received their biweekly payment now can do grocery shopping before being paid. Thus, in a country where a wide majority is poor and badly-paid, the app has processed more than 5,3 million requests –with an average purchase order of $140– and processes more than a million transactions per month.

While the recent enlargement of the gap between the official and black-market exchange rates for the dollar have affected the monetary stability over which Cashea was founded, Vallenilla says it is not a major problem, yet. “God willing, this can be resolved and resolved soon”.

Cashea hopes to soon expand to frontier markets in the Caribbean and Central America. While the regional venture capital boom of 2021 made Cashea’s leadership unsuccessfully want “to open a second country before the second year”, Vallenilla says, “I am convinced that before the third-year closes, we will have potentially opened our second country and, who knows, maybe our third one.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate