Mind the Gap

The difference between the official and parallel exchange rates for dollars and bolivars are increasing again. Why is this happening? How will it impact Venezuela?

SAN FRANCISCO, VENEZUELA, 23-08-2022. AUMENTO DEL DOLAR EN COMERCIOS DE SAN FRANCISCO.

I found a sign in Sabana Grande, a commercial area in north Caracas: Four apples, one dollar. As I did not have a one-dollar bill, I took out 40 bolívares in cash – more than one dollar at the official rate of 36.5 bolívares per dollar. “No, boy”, I was told, “here we charge the dollar at 50.” Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine writer, once said that money symbolizes our power to choose. The problem is when you don’t know how to express that power, whether at 36.5, 43.5 or 50 – if you are in Sabana Grande.

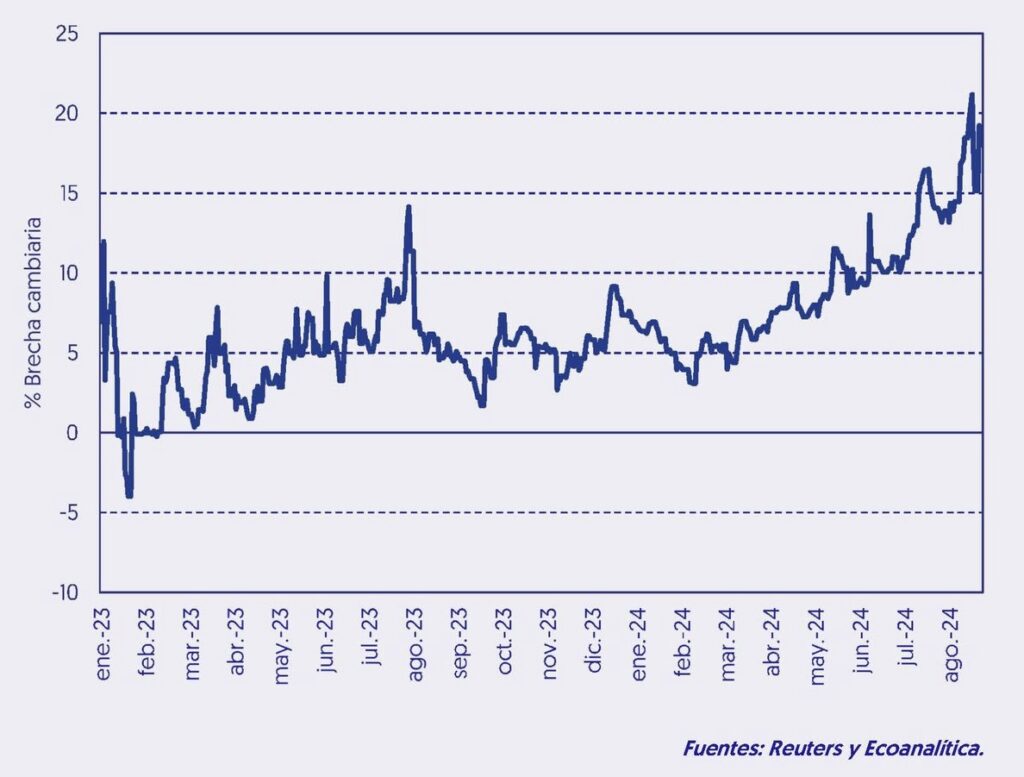

The exchange rate gap is the difference between the official and parallel exchange rates. It occurs when the price fixed by the official entity is not representative of the one determined by the supply and demand of foreign currency, something to which Venezuelans have been historically used to, and which has become relevant again: according to calculations made by Grupo 4,30, the gap went from 6% at the beginning of the year, to an average of just over 16% since the presidential elections, and more recently, up to approximately 20% this week.

In a country like Venezuela, where the dollar is so influential to define the price of many goods and services and to make all sorts of economic decisions, having such dissimilar exchange rates exacerbates uncertainty and hinders economic activity. But since there is a difference between the official and parallel dollars, each rate must be understood separately.

El oficial

The Venezuelan foreign exchange market follows a managed float system: it is configured to be determined by supply and demand of foreign currency administered by the Venezuelan Central Bank (BCV), which ends up having a high participation. Every week, the BCV allocates millions of dollars to increase its supply through interventions, thus offsetting demand pressures, so that the price of the dollar remains stable.

So far in 2024, according to data we have compiled in Grupo 4,30, BCV interventions have totaled more than USD 3.85 billion, and have been financed from revenues obtained from oil exports. The result has been a rate of 36.50 bolívares per dollar. Immovable.

Another reason for such stability has its origin in a more prudent posture of the government, in relation to how it manages its finances. According to Francisco Sanabria Rotondaro, financial analyst and professor at Universidad Metropolitana in Caracas, since fiscal revenues are in bolivars and part of the expenditures are indexed, an increase in the official exchange rate is disadvantageous to the government: Fiscal revenues expressed in dollars decrease; and although expenditures in dollars are the same, a greater amount of bolivars is needed to meet them, thus increasing the amount of money in circulation and generating more inflation.

A stable official exchange rate is in the government’s interest and it has acted accordingly.

In any part of the world, before each election, public spending and monetary liquidity are significantly increased, creating an electoral economic cycle. But in the recent elections, this was half fulfilled: “In the months of June and July, the government made a significant expansion of spending”, accumulating up to that moment an increase of 48%, with respect to the period January-July 2023, according to Asdrúbal Oliveros, director of consulting and research firm Ecoanalítica. Before that, the government had saved its spending increases.

It is not that an electoral economic cycle was not generated, but it was relatively smaller compared to past elections, and caused much less distortions.

El paralelo

The one-million dollar question (or, the 4.3 billion black market bolivares question, if you may) is, then, why there is a parallel rate in the first place.

One answer is that the current exchange system is not one of pure supply and demand, which ends up creating an overvaluation of the bolivar. In theory, this overvaluation would be corrected with an exchange rate of over 100 bolívares per dollar, according to Oliveros.

“To the extent that there is a surplus of bolivars in the system, this is transferred to the demand for foreign currency and puts upward pressure on the exchange rate”, Oliveros explains. But as the official dollar is below this level, distrust is generated and the incentives to negotiate at a more representative price within a parallel market increase.

However, not everything is mistrust, even less so in Venezuela: with a banking sector that is somewhat inaccessible for part of the population when it comes to foreign exchange. In fact, Ecoanalítica estimates that only one third of the foreign currency in circulation is channeled within the financial system. The other two thirds –approximately $4 billion– are in the private custody of Venezuelans or what Oliveros calls the mattress bank.

Since these dollars do not flow into the banking system, spaces for these currencies to be traded at a higher exchange rate than the official one are created. This is not viveza criolla: it is an arbitrage opportunity. But for Sanabria, only less than $1.5 billion ends up being traded at parallel rates – a relatively minor amount.

The Venezuelan economy is also influenced by the dynamics in the Colombian border zone. This year, the peso/dollar exchange rate has increased but, as the official bolivar has been stable, Venezuelan merchants on the border have lost competitiveness. To recover this competitiveness, Sanabria says, they have had to use a higher exchange rate than the official one.

In addition, Venezuela has a non-negligible informal sector, where the Law of One Price is likely being followed: that is, the same good should cost the same regardless of the place where it is observed. According to Sanabria, it is equivalent to acquire a good at the official exchange rate plus VAT, than to acquire it through the informal sector at the parallel exchange rate without VAT. Like the exchange rate gap, the VAT is also 16%.

Thus, when internal factors are combined in the exchange rate cocktail with external and more informal ones, the result is that only a small push is needed for the parallel dollar –and the gap– to increase. That push came in the form of the recent political uncertainty following the July 28th elections.

So… now what?

When you have an unstoppable force and an immovable force, the question arises as to which will break first. But in the case of Venezuela, it is possible that the current gap could be an equilibrium: that is, the unstoppable and the immovable forces go in different directions. No clash. No breakdown. No devaluation. Today’s Venezuela is not that of CADIVI nor that of DICOM.

Despite the growing political uncertainty, it is unlikely that the official exchange rate will be adjusted in the short term as long as the current flow of oil revenues keeps benefiting the BCV. Yet, according to Oliveros, “there is a latent threat that the licenses [granted to foreign oil companies by the U.S.] will be eliminated or revised”. Until this possible threat becomes a reality, Venezuelans will only live with the psychological effects of the exchange rate gap: uncertainty and confusion.

Borges also said that money was a repertoire of possible futures. In Venezuela, those possible futures are all uncertain. They can be at 36.5, at 43.5 or at 50. The problem is that, as each future is far from each other, consumption, savings and investment decisions can be distorted. That day in Sabana Grande I did not buy apples.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate