Chavismo Can’t Pick A Campaign Message

PSUV’s strangely troubled campaign reveals their readiness –or lack of– for Sunday's elections

If you lived in Venezuela back in 2012 then you definitely remember Hugo Chávez’s last campaign song. I was catchy, and it was everywhere:

“Chávez, Corazón del Pueblo”

The president was facing an uphill battle with cancer and a highly-motivated opposition, rallying behind Henrique Capriles Radonski. But the images of his carnivalesque campaign –the slogans, the songs, the rallies– all remain seared in our memory.

Now, what’s Nicolás Maduro’s 2024 campaign been about? It’s something about a cockfighting rooster, right?

Despite once being the undisputed lords of political communication, the government’s campaign has been messy and uneven both in tone and messaging. The entire endeavour feels incredibly rushed and improvised, despite Chavismo having set the date for the election themselves.

Messy actions

The government has been incapable of pushing a single clear and confident narrative for Maduro’s campaign. Instead, they’ve relied on small, petty and authoritarian actions that have allowed the opposition to slowly build an almost mythological epic.

Everywhere the opposition coalition went, the authorities immediately punished anyone who decided to publicly welcome them. For example, during the start of Edmundo González Urrutia’s campaign back in May, the national tax authority decided to close down the Maracay hotel in which him and María Corina Machado would stay.

These measures, clearly aimed at discouraging people from supporting the opposition along their route, just fired up the government’s detractors. That’s how we ended up getting free but invaluable campaign content like the videos of people asking Machado to come into their businesses, even if it meant the government would punish them for it. Cutting off bridges and roads had a similar effect of defiance from González and Machado, who were given golden opportunities to affirm the campaign’s “Until the End” slogan by simply bypassing these rather simple obstacles. What’s even more interesting is that, just a few days away from the election, this keeps happening, with Machado and González facing even more road closures during their trip to Zulia state.

The road blockages and petty closures don’t project the calculated confidence of a winning side that Maduro’s government usually tries to portray, but rather reek of poorly-thought-out desperation, while pushing a confusing ‘copycat campaign’ that ends up portraying Machado as the one calling the shots. This is more than just starting using flag-coloured hats to devalue them as an opposition symbol, as happened in 2013.

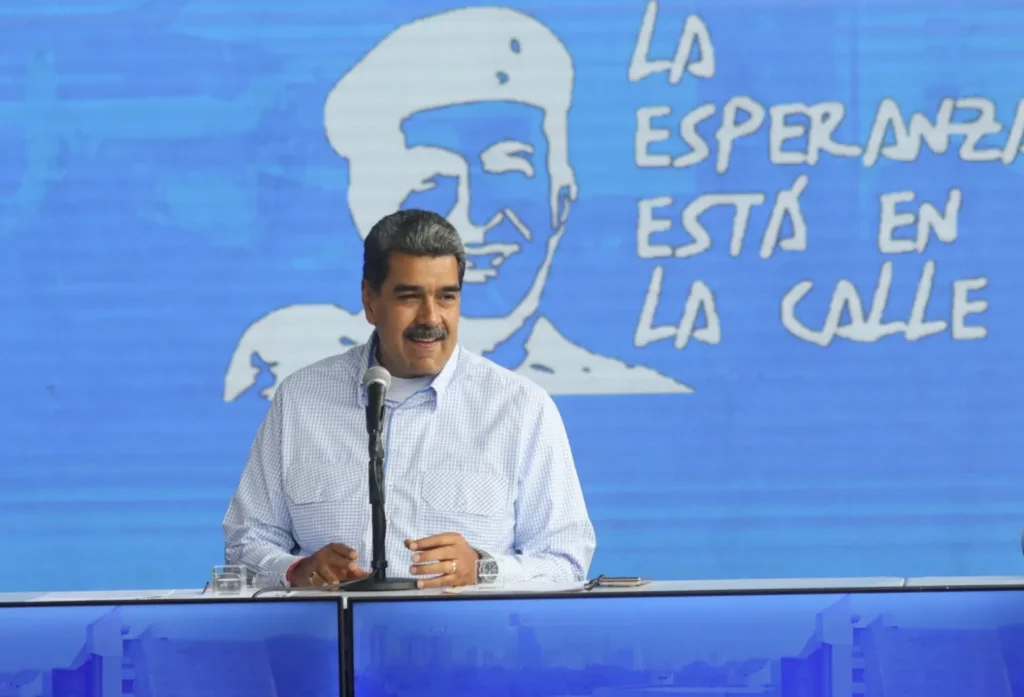

Wherever Machado goes, Diosdado Cabello announces a parallel rally – which sometimes ends in “Chavistas” leaving for Machado’s rally. In the 23 de Enero neighbourhood in Caracas, Cabello even asked the crowd to light up their phones: imitating a classic Machado move –widely viralized days before, after a rally in Apure– that represents the “light” that an opposition victory would usher in Venezuela. Even Cilia Flores seems to be imitating her tumbao and Maduro is showing posters of ‘alternative opposition’ candidates –seemingly to confuse voters– just as Machado tends to show a flyer of González Urrutia in her standalone rallies. In fact, Chavismo has even created Vente-like banners with Maduro over a blue background proclaiming that “Hope is in the streets”.

Messy messaging

On top of crafting the opposition’s media narrative for free and trying to copy it afterwards, Chavismo has had an incredibly hard time deciding on its own identity for the election. This isn’t new: PSUV’s self-image crisis has been going on for a very long time now, as the party struggled to find a voice independent of Chávez and the red livery of the revolutionary era. The last five years, however, have seen many identity missteps for Maduro as he’s tried to balance invoking Chávez for the traditional base while he forges a new nationalism and attempts to sell the public on a new forward-looking capitalism for Venezuela. It’s been quite the challenge and the government hasn’t been the best juggler.

The government’s lack of a clear vision of their movement has left them campaigning with a mix of classic Chavista ideas thrown in with more recent Pax Bodegónica-era slogans. This is how we get billboards on the highway that blame the opposition for 2017-era scarcity alongside yellow and green and pink hearts that read “Futuro” with no mention of PSUV. These ads and billboards co-exist next to large posters of Maduro’s face, his name written in bold lettering and a deep red: the traditional party colour.

In fact, PSUV has a series of odd marketing lines, as if five different agencies were hired to design campaigns and then they just approved all of them and ran them simultaneously. It’s gotten to the point where one has to wonder if any of this is actually helping or if it’s just confusing voters. Perhaps that’s the whole point, to confuse voters and keep them away from the actual opposition candidate. This would be a good idea if the gap between PSUV and the opposition was a lot narrower than what it appears on the polls. Instead, the government can’t really hope to win the election by simply scaring away opposition votes. Rather, it has to motivate its bases.

But the first step towards doing this is deciding on a message that will resonate with voters. Will your campaign be based around hope, unity, faith in a bright future? Or will you run a campaign of fear, by saying “the country will end in a bloodbath if the opposition wins”? The government has seemingly mixed both options. Caracas is now full of PSUV billboards with messages like “faith in our people” or “faith in our workers” next to ads that say “the Right Wing wants to take away public education”.

That second set of billboards and posters doesn’t even have Maduro’s name or the party’s logo on them, they’re just discrediting the opposition. This fear mongering has seeped into a lot of the PSUV’s messaging, which seems to clash with their “hopeful” billboards. Many murals have been painted around the country with messages that read “I choose peace, I choose Nicolás”. The implication is clear: if you don’t vote for Maduro you’re voting for war and violence, for guarimbas. Just like December 2002, during the oil strike.

This message is replicated by allies like Carlos Prosperi, who ran his own campaign in the opposition primary back in October before being co-opted. Similarly, Chavismo published a video ad in which a farmer rejects María Corina –represented by an actress not facing the camera, talking with a likely AI-made voice quite similar to Machado’s– after she tries to expel him from his land to privatize it.

Madurismo, in a certain way like the democratic elites of the 1990s, seems to have stopped knowing how to read Venezuela. It seeks to terrify with land privatizations in a country where its policies resulted in a devastated agricultural sector, opaque ‘strategic alliances’ that informally privatized public assets and internally displaced people. Similarly, Machado is no longer the representative of the wealthy sectors of Caracas. She is a leader who connects emotionally with the inhabitants –the ad’s protagonist– of rural and agricultural Venezuela and rallies crowds in Guanarito, Biscucuy, Mucuchíes or Barinas. It’s almost an anachronistic message from the Chávez heighdays.

The clash between the two messages is significant. But there’s a rainbow of other strange campaign stuff that the government has thrown into the mix. Did you know that Maduro has a rum brand out there for the election and is offering long colourful nails with the rooster logo? Have you seen the Maduro campaign truck with the Super Bigote wrap and that awful #NicoLike hashtag? Did you get to see the Gallo Pinto ad they ran in Times Square? Yes, Times Square in New York City. What even is the point of an ad running in a market without any of your voters? Was it just to show you could do it?

These decisions prove PSUV has lost the communicational plot. The complete lack of cohesion in messaging, tone and actions transmit that they don’t know or understand who they are anymore. And if you don’t know how to speak to your audience, you don’t know who your audience even is.

Not a good sign when you’re trying to win an election.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate