Delsa Solórzano: “No One Wants CLAP Anymore”

The former primary candidate shares her experience touring the country with María Corina Machado, where she witnessed the collapse of Chavista structures and faced repression up close and personal.

xr:d:DAFveawMeys:24,j:3110141041318316977,t:23100920

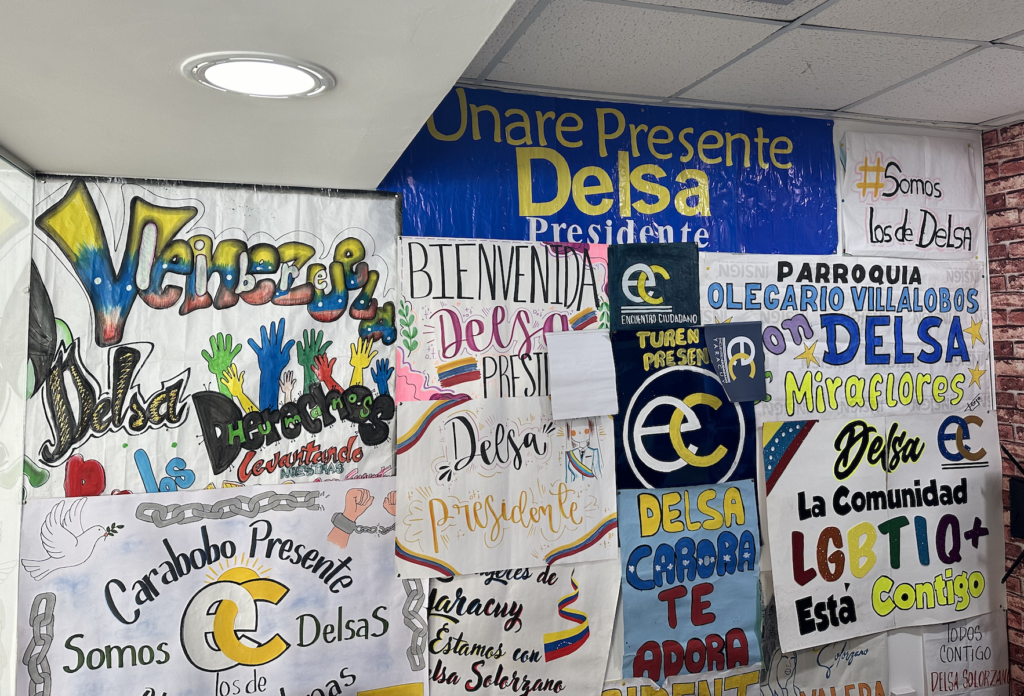

Delsa Solórzano, lawmaker of the National Assembly in 2015 and president of the opposition party Encuentro Ciudadano, has become a regular figure on María Corina Machado’s massive tours across Venezuela. A sort of de facto spokesperson for the Unitary Platform, Solórzano is one of the women catapulted to prominence in national politics after the primaries and the negotiations that defined the candidacy of Edmundo González Urrutia. At her party headquarters, in an office decorated with handmade signs given to her on tours and a map of Venezuela dotted with Polaroids that Solórzano takes to document her tours, she shows off a multicolored cluster of 263 rosaries that she has received since the tour started. Above it, a huge poster hand-painted by residents of Tucupita shows a sun rising over the Orinoco: “Delsa and María Corina – Young Deltans with Edmundo,” it reads, “Libertad Wirinoko anaba eku” (Freedom in the waters of the Orinoco, in Warao language).

“There are turquoise rosaries because the people of Vente made one for María Corina and one for me. People takes off their rosaries, with what it means to them, and give it to you,” he explains. She shows one with the Venezuelan flag colors, handed by a man at a church in Nueva Esparta. “He told me: it will accompany you and we will have freedom,” she says. “And I don’t take it off, it’s with me on every tour.” Solórzano relates how, upon showering after a rally, she finds rosaries on her body: “in my pants, in my underwear, people sometimes throw them at you, put them on you, put them in your pocket, in your bra. It is an impressive thing.” She shows a pair of pink rosaries: “It was a little girl and her mother. They took off their rosaries and put them on me, in Guárico.”

Solórzano, although constantly on the front line, remains impressed by the emotionality that the campaign led by Machado – accompanied by herself and other opposition leaders– for the candidacy of González Urrutia has raised in former Chavista strongholds: “It is a feeling of joy that I think Venezuelans hadn’t felt in years,” he says, “the country smiled again. Those rosaries are the renewal of hope.” In Upata, she says, people waited in the streets from 7 in the morning even though the rally was at 4 in the afternoon. In other places, she says, the border of the towns was blurred by the crowds: in San Juan de los Morros, for example, a woman assured her that she had walked from faraway El Sombrero to attend the rally. But, although she experiences the phenomenon on the frontline, Solórzano –like others in the Comando por Vzla platform – has suffered the repressive onslaught of the government: she has been expelled from hotels and two councilors from her party were de facto dismissed in Delta Amacuro.

“One time, it was one in the morning, we were arriving in Barquisimeto, and saw a checkpoint right at the door of the hotel. And I said: oh man, what’s going to happen here? I entered and there are three national guards in the entrance. “Are they going to let us sleep or not?” I ask. “Only the mounted police are missing inside,” a team guy tells me. There was the SEBIN, the DGCIM, the DIP and a new thing… What’s the name? I can’t remember. “What’s wrong?” I ask. “You can’t touch anyone if you don’t have a court order.” An agent tells me: “I am the authority.” I told him: “No sir, the authority is a judge and the judge has to give me the order. Nobody is going to hand over their IDs here! “Everyone, let’s go upstairs.” We took the keys, and we all went to my room and the National Guard was setting up a riot. I was mothering my boys. Then, a guy dressed in civilian clothes knocked on our door: “You have to leave the hotel, this is a raid.” I said, “Is this a raid? Well, let them raid the hotel down there. But my room is private after I pay for it, you have to bring me a court order.” The guy leaves.

One of the boys had stayed a block earlier, buying fried chicken. He did not see the pod. They knock on the bedroom door again and it was him with two bags of chicken. There was a guard at the elevator. And he tells her: “your boss is angry; she scolded me and didn’t open the door for me.” I open the door; he arrives with the chicken and everyone is like: “We’re all in jail and you’re buying chicken!” We spent about 15 or 20 minutes, imagine the uncertainty. At the end of the day there are two of us adults [on the team], the rest are kids that their moms put under my care. “What do I do? How do I get them out of here? How do I get them not to touch them?”

The National Guard returns and knocks on the door: “this is a raid.” I become a ten-foot guy: “I already told you no, if you don’t bring me an order. And if you have any real chance of doing anything, take me to jail. What do you think? But call first. Call [Nicolás] Maduro, Jorge [Rodríguez], Delcy [Rodríguez], the Caveman [Diosdado Cabello], everyone. If you miss one, you’re the one who’s going to get screwed. Come on, then. Because to touch them, you have to touch me first. I’ll wait for you here, don’t come to my room. After you have called them all and they have all told you that you can take Delsa Solórzano prisoner, give it a try.” He got scared and left. When I see that the man is going down in an elevator, we start running to the unloading elevator to leave from behind. We were leaving, fleeing, escaping. But obviously people always help you: because you couldn’t escape if there wasn’t someone who opened a door for you, if there wasn’t someone who omitted your name or forgot that they saw a strange Arab woman entering certain places. Because that day we went out normally, but I have had to dress up: from putting on a yellow wig, which doesn’t look very good on me, to putting on a burqa. I have had to do everything to get through, because sometimes you need a bed after spending two days in a van.

And have you had confrontations with irregular groups of Chavismo, such as colectivos?

Once we were in La Guaira and I was with a beautiful lady, today she is part of the party; she is a beautiful black woman with yellow hair, an afro. At that time, she was not a member of the party, but she stood next to me. Some colectivos came [to intimidate us] and Daniel [communications director of Encuentro Ciudadano] was fighting, because we take care of each other. And a colectivo comes. I’m very small and if he puts a hand on me he knocks me down. But the old woman approaches with such an energy and tells [the colectivo]: “So and so, I didn’t raise you like that.” I say, “Oh my God, what is this?” And she tells the colectivo: “Do me a favor and go home. Because you may be big, but I’ll hit you with a flip flop anyway. You’re leaving now, don’t screw around.” And the guy: “Mom, they are traitors.” And the lady tells him: “You are leaving. I am with Dersa.” And the guy turned around and left.

Would you say that the PSUV structures are weakened in the regions?

I don’t see the PSUV anywhere. I see a clientelist structure, which is not the same as a political party.

And do you see that clientelist structure weakened?

It is weakened because it was based on “what can I give you?” The CLAP does not arrive, the gas cylinder does not arrive. You go to Altos de Lídice –we did it yesterday– and you see that there is even discrimination in the CLAP bag. The lower part of the barrio gets a type of food. It is always an inedible thing. But this week chicken and mortadella arrived in the most urban part. Chicken and mortadella did not arrive at the top. Rice with worms arrived. I saw it. Nobody told me that. Also something arrived that is like flour and everyone complains about that flour and the grains arrived. No proteins arrived at the top of the barrio. People tell you: “I don’t do anything with that.” There is a woman who told me: “I eat twice a day.” Eating [in that case] is a single arepa, viuda, and in the afternoon any little thing she has. “I could eat three times,” she tells me, “but I’m not going to eat that.” Do you know what people are doing? People receive CLAP to give it to those who have even less. Now something called the exchange is in fashion, they go around like the old clothesman from El Chavo del 8: “Exchange, exchange, exchange.” So if I have a plantain, I will exchange it for something else. The CLAP barter.

You have mentioned that you have also seen the beneficiaries of these clientelist networks, for example, municipal employees, going to you and María Corina Machado’s rallies.

We have seen it. They end up hugging and crying and asking you for a photo. María Corina and I always eat in the same place on the road when we pass by. The bathroom is in the business next door. The owner comes out and says: “I want a photo with her.” I tell him: “of course” and I take off my bracelet, which says, “todo el mundo con Edmundo” and has the logo of the Unity, and I give it to him. The photo is taken. And when I leave, he tells me: “We are going to win, Venezuela needs change. I was a Chavista.”

The number of non-Madurista Chavistas that you find on the street is overwhelming. The people who work in the mayor’s offices. You go to the hospitals where it is assumed that everyone is Chavista and where the one who is going to treat you is the one who depends on CLAP. There the Chavistas go, the “jefe de calles” –who are generally women– touring the hospitals, noting who came, who did not come, who they treated, why they treated them and how they treated them. But when you leave the hospital, the people there –who spend five, six, seven days waiting to be treated– tell you stories and tell you what they have suffered. I tell them: “I don’t greet you right away because I’m afraid that they will take away your CLAP.” And they say: “Why are they going to take away my CLAP if that shit is of no use? If they take it away from me, I don’t care.” People no longer want CLAP. We are experiencing that everywhere we go.

We have photos of people with their 4F caps, with their PSUV t-shirts, who are in the rallies [of María Corina Machado], listening to the speech, supporting what is said, asking God, hopeful again. That’s when you understand the concept of “spiritual struggle” that honestly, I never understood much because regardless of how religious I may be, this is an electoral struggle against a criminal dictatorship.

And have you seen these sympathies in the military sector, in the checkpoints, for example?

Impressive things happen in the checkpoints. We have seen in dozens of checkpoints, dozens, that they make you the military salute: the guys stand from side to side and stand. They salute María Corina. I have seen it. It’s not something I was told. This is happening in every corner of the country, look we have traveled the country from end to end. There is no corner we haven’t gone to. I toured the country at least four times last year and that was already happening. Today that there is unity, that there is a candidate, that there is a party card, that there is a date… change is in the street. There [in the Encuentro Ciudadano office] are the people from Caracas and Miranda auditing [the table witnesses]. And they are receiving threats. The colectivos tell them: “if you are going to be a witness… poor family of yours.” And the answer is: “Yes, it doesn’t matter: overall, what are you going to take from me? My skateboard?”.

Once we arrived at a checkpoint in Delta Amacuro. They had told us: “you are not passing by.” I told him: “Oh, love, yes I am going to keep going.” The soldier says: “Maduro has an event on the next street.” And I tell him: “Ok, no one is going. Better. Because when it’s over, they leave for our rally.” He answers: “Diosdado said.” Then we stop at the entrance of a place and a soldier tells us: “Park to your right.” I park. Then, thirty meters later, they stop me again and say, “park to the right.” And I tell him: “My love, how far to the right am I going to go? If the only thing to the right is your station.” And the guy tells me “to the right, because the left died.”

Look, in Bolívar a checkpoint stops us and there is a female official. They lower the glass, and she doesn’t see me. And she asks the driver for 20 dollars. I show my face and that’s when she realizes that I’m in the car. Look, when that woman saw me, I felt the colors drain from her face. She was terrified. I tell her: “You’re asking for money, really? Don’t you know that that is a crime?” She tells me: “Delsa, don’t record me. I have been standing here for two days because I don’t have watch relief, what I have is hunger.” I took out the package of bread with Diablitos that I had in the truck and gave it to him. Always after they leave you, they tell you: “change this, don’t let yourself be screwed” or they tell you “Women don’t let themselves be screwed, it’s different.” I think it also has a lot to do with the fact that we are women and people trust us more for some reason and it has to do with the need to give our children the country they don’t have today. I think there is a connection with that.

Speaking of female leadership, how has that duo with María Corina Machado worked on tours?

Great! Obviously, it’s not easy. There are two people from the tour team, María Teresa Clavijo –Aragua coordinator– and another girl from the team and well, we put her in stage between them and me. If you bend down to say hello, if you are careless, they will pull you. You need someone to grab you by the pants. It happens to me and I’m not María Corina. We accompany each other so that things go well. When you admire the person you are working with and with whom you are fighting, things flow better.

Also, for women this is so difficult. Hearing all your life how they’ve called us… “that little woman”, “the crazy one”, “oh, they are women”, “you woke up in a bad mood, you have your period”. You hear that all your life. I have chosen that, every time I am going to start a mess, I say “let it be known that I don’t have my period today.” It is complicated and knowing that today that the country for the first time realized that we are human beings and that we are equally capable of leading, you feel that you have achieved it. And that we are opening the way for the girls who come behind, so that they do not have it as difficult as we had.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate