Venezuela Is Losing Its Last Glacier. What Does This Mean Exactly?

Global warming is not the sole culprit but the thaw will transform local ecosystems – and its microorganisms

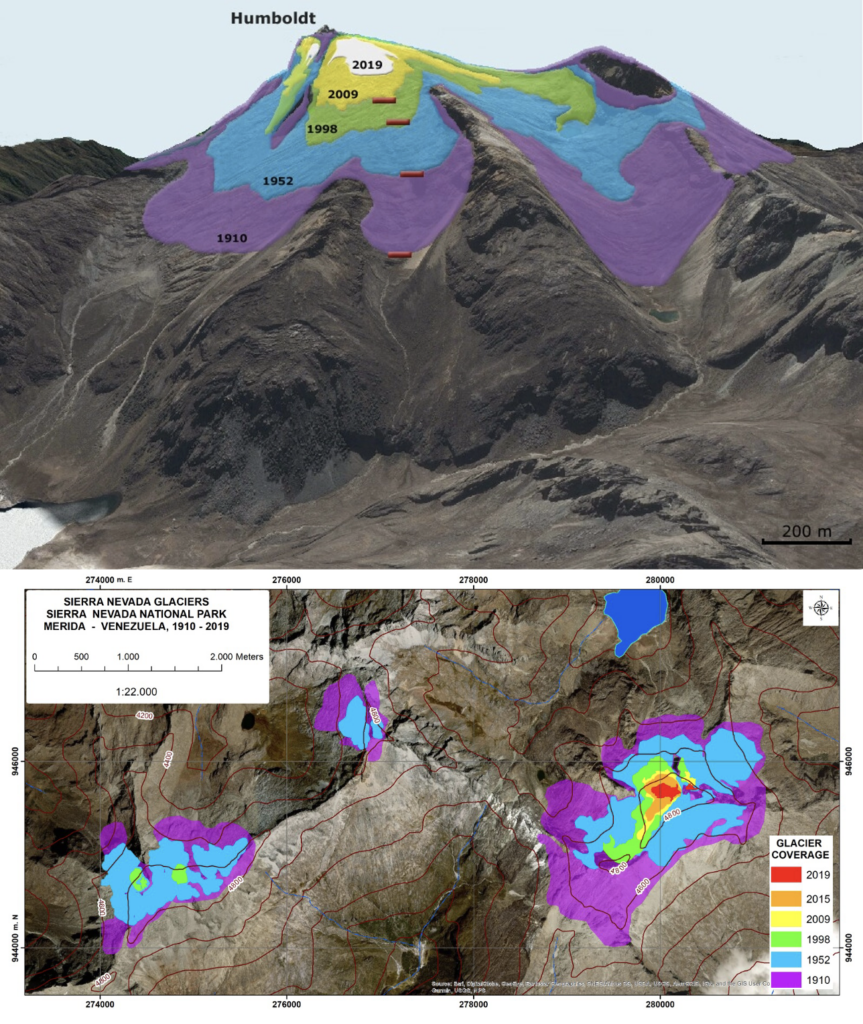

Venezuela's last glaciar La Corona in Pico Humboldt.

In 2019, the funeral of what is considered the first “dead” glacier due to climate change was held in Iceland. Okjokull was a body of ice that, by 2014, had already lost enough vigor to no longer be considered a glacier, and that in 2019 was declared extinct in a commemorative event that sought to promote reflection on global warming.

Iceland, however, still has an abundant number of glaciers. Venezuela, on the other hand, will be the first tropical country to see all of its glaciers disappear. The three highest Venezuelan peaks are Bolívar (located at 4,978 meters above sea level), Humboldt (4,942 meters above sea level) and La Concha (4,922 meters above sea level). Two of them have already run out of glaciers and the disappearance of the one that remains in the third one is unstoppable.

According to information collected by the Venezuelan climatologist and ranking member of the Intergovernmental Group of Experts on Climate Change (IPCC), Rigoberto Andressen, La Concha peak ended losing all of its glaciers – known as Ño León and Coromoto – in 1990. Bolívar Peak, for its part, saw the last remnants of its peaks –Timoncito, Espejo and El Encierro– retreat in 2017, but by 1991 these were already in the process of retreat, according to ecologist Luis Daniel Llambí.

The La Corona glacier currently covers less than 2 hectares, according to Llambí, who has carried out different projects studying glaciers in Mérida. This arduous work has been accompanied by experts such as the ecologist Llambí, the geomorphologist Maximiliano Bezada, the geographer Nerio Ramírez, the physicist Alejandra Melfo and others, who have offered important publications such as Se van los glaciers, by Fundación Polar, and Last Glacier of Venezuela, from National Geographic.

Glacial geology as an answer

Venezuela becoming the first country in the tropics to lose all of its glaciers is a natural fact that is anchored to ancient geological and geomorphological processes. “Glacial history is very complex and climate change cannot be deciphered solely based on the disappearance of a handful of glaciers in a few years,” says Professor Maximiliano Bezada, doctor in Paleoecology. “The advance and retreat of these began at least 12,000 years ago,” he explains, “For example, when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in Mérida, in the 16th century, they found a completely white mountain range. There is evidence that the glaciers advanced up to 4200 meters in altitude. This period is known as the Little Ice Age.”

According to Bezada, in the 9th century, however, the ice retreated drastically in what is known in geology as the Medieval Warm Period. “It is evident that the rise and fall of ice is a natural process that remains dormant and that responds to a whole amalgamation of geographical and astronomical conditions,” he says, “it is not an unprecedented phenomenon.”

For Bezada, the fact that the Humboldt glacier has not yet disappeared is due to a whole set of factors, the explanation of which lies in science. “In glacial geology we use a concept called ‘snow balance line’, which refers to the average limit to which ice can descend in the mountains,” he says. “Currently the balance line is located at 5,400 meters above sea level. That is why in other Andean countries such as Argentina, Peru or Colombia still have well-preserved glaciers.”

The reality pointed out by Bezada is portrayed in specific events, such as the disappearance of the Timoncito glacier, the last remnant of ice from the highest peak in Venezuela. Bolívar Peak is positioned 36 meters above Humboldt Peak, but despite being the highest peak, it ran out of glaciers in 2017, before Humboldt. This is due to the orientation of the peak’s relief under the sun. The Bolívar glaciers were on the south face of the summit, so their exposure to the sun’s rays was much higher than that of the Humboldt glacier, nestled in a natural rocky shelter from solar rays.

In fact, because they are located near ecosystems as biodiverse as humid forests or páramos, tropical glaciers tend to preserve a greater number of microorganisms inside than polar and subpolar glaciers.

Melting, in turn, brings other implications related to hydrography. “The definitive melting of the La Corona glacier will mainly affect the wetland system near the Verde and La Coromoto lagoons,” says Bezada. “Although the Humboldt glacier is not decisive for the subsistence of these two bodies of water, it plays an important role for the wetlands immediately around them, since the runoff from the ice cap injects water into them.”

These wetlands make up the sources of some tributaries to the Chama River basin, which is one of the most important water courses in the state of Merida and the Venezuelan Andes.

New ecological niches

When the environmental conditions of an ecosystem change abruptly, new species appear to develop occupation strategies, colonize those spaces and configure new ecological niches. This is already happening in the areas immediately around the remnant of the La Corona glacier. Experts call this ecological succession and, in this case, it is taking place when the glacier ice retreats to allow the thermal comfort that pioneer life forms need.

Ecological succession can be of different degrees, depending on the number of times it has occurred. But what began to occur on Humboldt Peak and its glacial edge is an unprecedented case of primary succession in which new microorganisms that are also part of the local biodiversity began to proliferate in vertiginous life after the melting of the La Corona glacier.

These microorganisms were encapsulated in the ice for millennia, but their capacity for extreme adaptation allowed them to remain alive in inhospitable conditions by taking advantage of small amounts of nutrients and liquid water present within the ice body.

In fact, because they are located near ecosystems as biodiverse as humid forests or páramos, tropical glaciers tend to preserve a greater number of microorganisms inside than polar and subpolar glaciers.

Dr. Alejandra Melfo has closely worked on primary succession processes in the glacial environment immediately around Humboldt Peak. “What happens when the glacier retreats is that the rock is left bare, with no form of life on it except for some bacteria,” he explains. “The rock is exposed to the possibility of being colonized by new forms of life.”

Melfo describes it as a process in which bacteria and microorganisms that were encapsulated in the ice for a long time arrive first, followed by lichen and other life forms capable of adhering to the rock. Lichen is associated with moss, the collective term for rootless plants capable of populating a rocky surface as long as they have water, even if they are devoid of soil. Melfo catalogs the moss-lichen association as “biocrusts”, a structure that helps weather the rock, retain water and, when it dies, may be incorporated as organic matter to consolidate incipient soil.

For Melfo, it is not clear whether the new ecosystems that will proliferate will be identical to those of the neighboring páramos or how long it will take to reach similar ecological conditions. But it is a fact that this environmental reality stands as a living laboratory that must be studied, especially in a panorama determined by climate change, in which biodiversity is in suspense for new adaptation strategies.

Controversial measures

In December 2023, the Venezuelan government announced an action that, according to the regional government and the Ministry of Ecosocialism (Minec), sought to “minimize the transfer of heat from the rocks to the mass of ice”. The operation consisted of installing a geotextile fiber material –a kind of temperature-regulating blanket– on the edge of the La Corona glacier.

To date, there is no concrete, photographic or informative record regarding the effective execution of the project, beyond a couple of brief press releases and some photographs of the geotextile being transported by helicopter. There were also no public reports detailing the resulting environmental impact or, at least, a logbook validated by experts.

The latest official information on the progress of the operation is from February 2024, when Minec announced that the geotextile material had been successfully transferred to shelters in the high Andean páramo of the Sierra Nevada National Park, and that it would then be transported by land by forest firefighters and park rangers to the edge of the glacier and extended next to it. As of the date of publication of this article, it is not known whether the geotextile fiber is already next to the glacier or not.

This whole series of government announcements made a lot of noise within the scientific and academic community, as well as in the different rescue and mountaineer groups, since they consider it arbitrary to proceed to intervene in the ecosystem abruptly without previously carrying out studies that weigh the possible environmental disturbances that this can bring to ecological niches and biodiversity.

At the beginning of the year, in the heart of the city of Mérida, a collection of signatures was called by environmental activists, university researchers and different social actors to take a stand against the announcement of the implementation of this policy. Likewise, entities such as the College of Geographers or the Merideña Mountaineering Association issued their respective statements, also opposing the measure.

An anonymous source within the government of the state of Mérida told Caracas Chronicles: “All the controversy that arose is due to a political factor. If it had been an NGO or a group of university researchers that made the proposal, it would surely have met with fierce criticism from the government, and the same people you see today criticizing the measure would perhaps be praising it as an innovative action,” this source says. “The truth is that this geotextile fiber hardly releases microplastics and microparticles, very contrary to what some ‘experts’ say. Some of those who criticize do so for very valid reasons and what they demand is environmental oversight, but another group turned the issue into a source of sensationalism. The government says that there will be monitoring of this material and that it will be removed once it fulfills its function. That will have to be seen. The geotextile is made of a thermoplastic polymer that guarantees breathability and can certainly absorb excess heat from irradiation.”

Melfo prefers to limit herself on giving an opinion regarding geotextile policy. “I don’t have enough concrete data on what is being done to give you an objective opinion about the possible reactions of the ecosystem and the glacier itself once this measure is applied,” she says.

For his part, Bezada calls the measure an “absurd, unviable project.” “The geotextile strategy is viable as long as there is seasonality, which is why it has been implemented in Europe, where it has been done mainly to maintain ski slopes located at latitudes above 40° North,” he explains. “But our summits don’t have snowfall remaining due to latitude but to altitude. In the tropics we do not have we do not have winter or summer, and the lowest temperature of the year is relatively similar to the highest. This fact nullifies the effectiveness that the geotextile may have.”In any case, the disappearance of the La Corona glacier has touched fibers associated with cultural roots and environmental awareness throughout the country. “The disappearance of the Humboldt Glacier is, above all, a cultural and historical phenomenon. It will have an impact on tourism, mountaineering and especially on the way we perceive our mountains,” says Melfo. “On the other hand, the most significant impact has to do with the wake-up call that this fact should be for us to reflect about climate change.” Uruguayan singer Jorge Drexler said goodbye to our glaciers in style. Let’s do it too.

Cover photo: José Manuel Romero

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate