How the Cocoa Boom May Impact Venezuela

The supply-demand gap took the global price of this fruit to levels not seen in 60 years. Does this mean prosperity for Venezuelan producers?

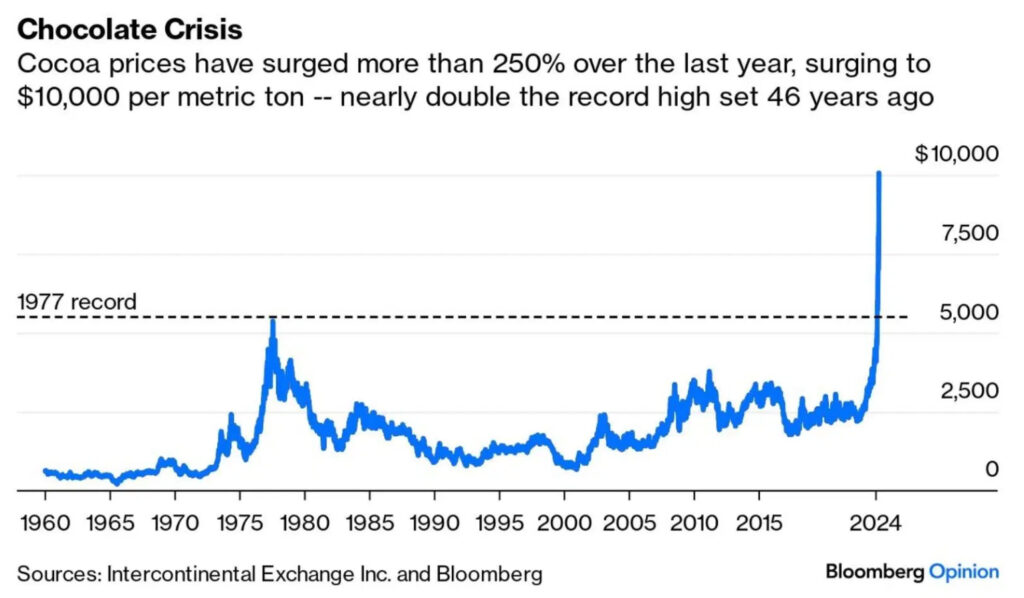

For six decades, cocoa was a cheap product. This defined the ways this economic sector organized itself around the world, and the size of the investment in each region to increase quality and yield. But now, a new appetite for chocolate and climate change merged into a price change so big that is altering the fundamentals of the industry.

According to Bloomberg, global consumption in 2023-2024 will be way over production, something never seen since the early 60s. This is the third deficit year in a row, explains the Venezuelan expert Helen López, director of Madrid’s Escuela de Chocolate. “From January to late March, in the New York exchange, cocoa went from 2,000 to more than 10,000 dollars per ton, which broke a low price phenomenon that lasted during the last 60 years.”

There are several reasons for this. The two main producers, Ivory Coast and Ghana (which yield 70% of cocoa world production) have been unable to meet their production commitments for three years, among other things because of climate change. El Niño and La Niña have increased drought or floods that damage plantations and stimulate plant disease. By the end of March, Ghana announced its harvest would be half the expected: a bit more than 420,000 metric tons, its lowest in 22 years.

The result: some areas are yielding half of their traditional tonnage, while global demand keeps growing with the surge of emerging consumer markets in Asia and the Arab world. “The planet is eating more chocolate,” says López. “In fact, demand has been growing more than 4% a year for a decade.”

So the hike price in the cocoa from Ivory Coast and Ghana reflected in the New York exchange, became a global price hike, and reached Venezuela, where cocoa reached an average of 5,000 dollars a ton. This is equivalent to 5 dollars per kilo of F2 medium quality cocoa, which at the end of 2023 was being sold from 1.50 to 3.50 dollars per kilo.

The sector responded by buying cocoa futures in mass, causing a lack of liquidity that brought the price down dramatically. As the time of writing, the global price of cocoa is subjected to intense instability.

However, as Venezuelan producer Douglas Dager says, the global price hike has little impact in Venezuela, because “our productivity is very, very low. Our plantations belong to low income farmers and the business is not in cocoa production, but in its sale, distribution and processing into products like chocolate, which uses a lot of vegetable fat and little cocoa at the industrial level, and pharma industry.”

So, for Dager, the pressure coming from the increased consumption of cocoa by-products “is going to have a sudden stop” that would stabilize the price on a more honest level, “around 4 dollars per kilo, 4,000 a ton.”

The opportunity within the crisis

Can we think, or dream, that a global cocoa boom means at least a good stimulus to rebuild the Venezuelan cocoa sector?

Does this mean that, just after Chavismo killed our oil industry, we can enjoy a cocoa boom, just like in the 18th century?

Not necessarily.

According to Helen López, and speaking in global terms, the big chocolate factories will bet on the so-called analogs: chocolate versions made with by-products such as cocoa powder and grains from other origins. “We are already seeing on the shelves products with additional flavors, or more creamy and fondant, which respond to the need of replacing cocoa with other ingredients. Small factories risk closing if they are unable to absorb cocoa’s new price. In markets with little maturity, like Venezuela’s, where there are no consumption peaks like Easter, it is more difficult to break the price barrier with products like bombons or tablets.”

In Venezuela, to add any other ingredients to a chocolate product means to deal with expenses and complications that don’t exist in a developed economy like Europe’s. Venezuelan chocolate makers will have to think twice before replacing a tablet with a bonbon or a chocolate pill with less cocoa that integrates additional costs in ingredients, processing and packaging.

For the Guarataro cocoa producer Albe Gorrín, “the huge price hike is an stimulus, an impulse, and a bit of help: the price increased, we have more producers now, and if we want cocoa to be a dynamizing sector of our economy we must understand that the new situation will bring more competition and bonanza for those who know how to use it.”

Gorrín and Dager agree on the need of taking advantage of this opportunity to improve processes and standards in the plantations and in the following stages to protect and transport the fruit or beans without risking their quality, as Ecuador, Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico and the Dominican Republic have already done.

This effort has already started. In general, plantations keep working with practices that cause a minimum environmental impact, and try to be sustainable. Producers are also reforesting with local cocoa trees to preserve their genetics, recover the canopy and improve the environmental equilibrium. There are practices that associate conservation and cocoa production with green tourism, while chocolate makers insist on training producers to guarantee quality on every step after the crop.

“One insists on increasing production”, says Gorrín, but according to the changes in the international norm, which take into account preservation of forest, soil and water bodies. Here, in Guayana, cocoa is useful to fight deforestation caused by irregular mining.”

López adds that having the best genetics is not enough. Higher quality standards must be met. Now that the price became another thing entirely, it might allow investments that had no economic sense to this day.

A law project, another problem

Producing cacao in Venezuela means, for instance, that you can have no profit at all, just by buying gas to get your product to the buyer. And now the National Assembly is discussing a new Ley del Cacao.

This law, according to the draft, expects to “protect and promote cocoa production and connected activities”, but, as it is now, it would involve the government in the production and commercialization chain, while it would reduce reasons to preserve the sensorial quality of Venezuelan cocoa, which is only possible by meeting some technical and sanitary requirements.

Once again, what is a strictly economic and commercial affair is being turned into a political debate. Producer Gorrín knows about some dialog tables, but he hasn’t been invited “because I belong to a certain federation and not PSUV”. He thinks that the State cannot be the ruling entity, the producer, the buyer and the exporter. “One wants to take profit from these new prices to improve production and compete globally, at foreign markets where quality and not political relations matter, and no, we can’t because here the issue is being politicized instead of focusing on production and domestic competition.”

Despite all this, Venezuela exported 300 tons of cocoa from Mérida to Estonia and Indonesia, an achievement that leaves more doubts than joy.

Juana Gómez, from the national association of Venezuelan cocoa producers (ASOPROCAVE), says that farmers “are not charging the new price because of the difficulties to produce. Besides, this new law promises no benefits for us. It fixes prices for the industry and the processing factories, a clear example of the fact that the price is not our problem, but productivity, the lack of greenhouses, the recovery of soils, the financing. It’s good that the law is about cocoa, but it doesn’t consider its producers, the people who grow cocoa. Once again, the government makes its plans and we don’t see how they have to do with us.”

Meanwhile, the final product sector awaits for the impact of the price boom on Venezuelan cocoa. In Miami, the Venezuelan chocolatier Isabel García Nevett, co-owner of a chocolate store that promotes its use of Venezuela-origin cocoa, tells they have already sensed the change in the Venezuelan chocolate they source, but only among many other price hikes in the inflationary context of North America since the pandemic. “We use mostly Venezuelan chocolate. The supply is stable so far, even if the price changes. I don’t know how the market of Venezuelan cocoa will behave in the future, but it’s always paid at a premium price because it’s hard to find.”

In this company, the plan is to keep using Venezuelan cocoa. “It’s an aspect appreciated by some clients, those who come from Venezuela, and those who really know cocoa and chocolate.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate