Adopting Jesús, Epilogue: Becoming Gringozuelan

Final words by the author with a cool conclusion that'll warm your heart

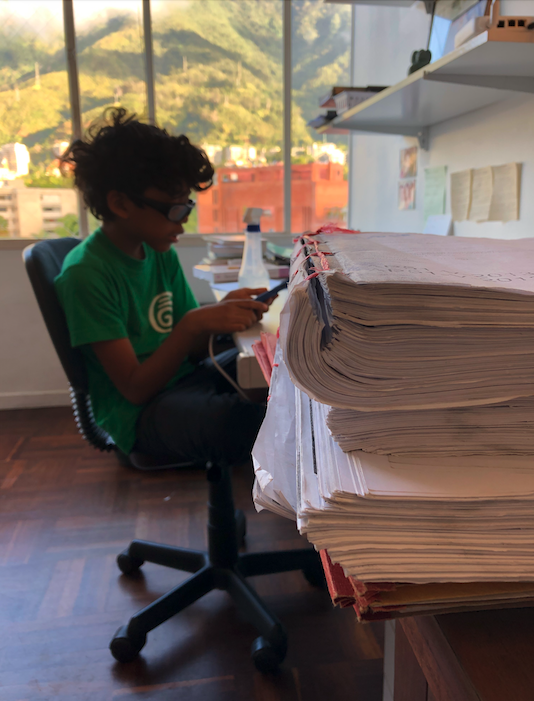

Illustration by Platanohay

As I approached the window of the U.S embassy to inquire about a passport renewal, the official looked confused. It was the olden days, when there was still an embassy in Caracas. After a brief exchange in Spanish, she told me I needed an appointment.

Aquí es con cita previa.

In fact, the embassy’s drop-in center allowed American citizens to arrive without an appointment. But she had made my favorite mistake. She had confused me for a Venezuelan. Glancing at my U.S. passport and unmistakably American last name, she gave me a confused look and passed me along to a consular officer.

Moments like these are part of what I consider a crowning life achievement – moving to Venezuela and managing to get confused for a local. Over the years the catch-phrase “I thought you were Venezuelan” was my favorite thing to hear, second only to “You’re an American? Really?” It’s a middle ground I’ve come to think of as Gringozuelan.

I had the advantage of having both a natural aptitude for languages and a bilingual elementary school education. But language was about more than just communicating with Venezuelans, it was about the experience of speaking in venezolano. It was being able to rattle off phrases like “Que vaina ejasa woong?” or “Estaas tu chiquito.” Or learning the exact voice inflections of “Hace uuuff” “ People would say that I sounded like a cross between a maracucho and portugués.

I couldn’t tell if Venezuelans thought I was foreign or not.

I stumbled into Venezuela after a year in Puerto Rico working with a friend who had spent time in San Antonio de los Altos. I got to Caracas in 2001 with a thick Puerto Rican accent and a plan to spend six months teaching English. I wound up journalism, eventually at Reuters, watched chavismo’s rise, moved to Brazil for three years, then moved back to Caracas with a plan to adopt a kid.

I couldn’t tell if Venezuelans thought I was foreign or not. Some seemed surprised, some people seemed to know off the bat. Some would chat with me for an hour and then after learning my nationality would say “Oh I totally knew that.” (Tarde piaste, pajarito.) In some parts of Latin America I could feel the steely gazes reserved for foreigners. In Caracas nobody looked at me. They might or might not have known I was foreign. They definitely didn’t care. It was one of my favorite things about Venezuela.

Two decades after I started that adventure, I’m seeing the same experience in reverse through my son’s eyes. He’s an American who only recently arrived in his country, and he’s taking it in the way I did when I got to Venezuela. Schools are so big here, he says. The roads are so easy to drive on, he tells me. He’s excited for what he says will be his first summer vacation (in Venezuela they don’t call that, in part because there isn’t really a summer). His teachers tell me he’s curious and inquisitive and makes everyone laugh. He’ll break into the National Anthem on a moment’s notice. He proudly sports his DC United jersey whenever possible. Soon his English will be peppered with teenage slang that his dad will be unable to understand. He, too, is becoming Gringozuelan.

Chapter I: Finding Joy In a Hopeless Place

Chapter II: He Called Me “Papá”

Chapter III: Suing My Son’s Mother

Chapter IV: They Made the Adoption Possible

Chapter V: “He’s my kid. Nobody believes me”

Chapter VI: Immigrating to Lady Liberty

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate