The ENCOVI Shows a Geographically Unequal Venezuela

Food insecurity decreased but remains, inequality is high and poverty hasn't changed much from 2022: the new UCAB survey reveals that the pandemic effect is fading away, but the humanitarian emergency is still there

On March 13th, Andrés Bello Catholic University in Caracas published the 2023 National Survey on Living Conditions (ENCOVI). This year, UCAB rector Arturo Peraza said, the survey is concerned about “structural conditions” of Venezuelan society and is emphasizing public policy proposals “in which Venezuelan society can reach agreements” for collective needs and “structure responses.”

The survey explored poverty, income inequality and food insecurity –as usual– but went more deeply into geographic inequality and the crisis of the educational system.

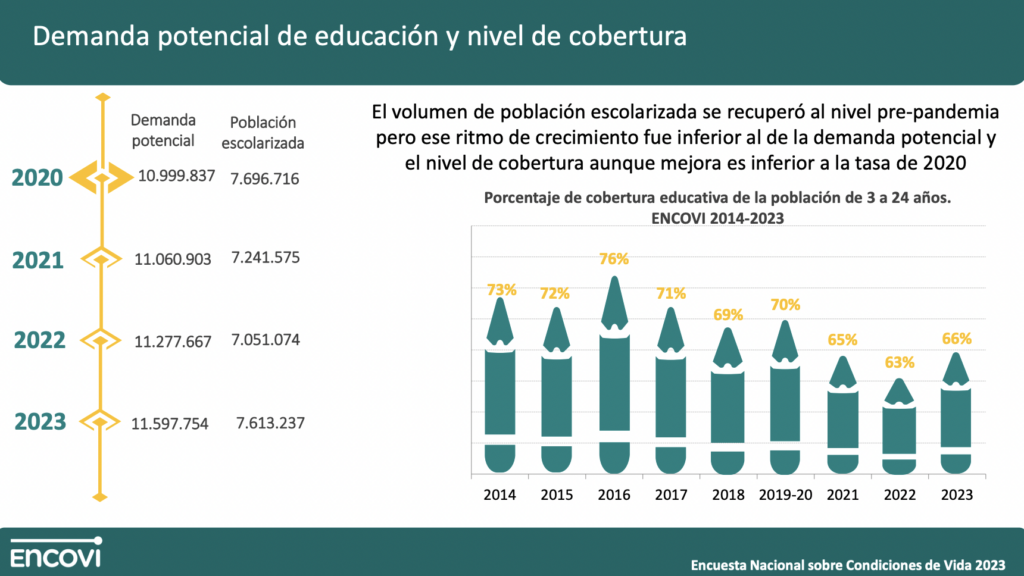

According to the new ENCOVI, in 2023 the volume of the school population recovered to pre-pandemic levels (7.6 million children) but the growth rate was lower than the potential demand. In fact, the coverage percentage is lower than 2020 (70% vs. 66%). Similarly, only 60% of students regularly attend classes with some normality while 40% have irregular attendance for multiple reasons, including lack of food (10%) and teacher strikes (30%).

School meal programs are now covering less people. While 62% of students say they are beneficiaries of school meal programs, only 27% say they have these subsidized nourishment every day –down from 44% in 2022. Similarly, as the economy has worsened, fewer and fewer students have access to private schools: from 34% in 2015 to only 12% in 2023.

Teen moms

Venezuela remains a fecund country. The rate of children per women has risen from 1.97 in 2021 to 2.01 in 2023 – but less than the 2.18 the UN registered in 2019. Nevertheless, an early fecundity persists in Venezuela: 45% of the 15–25-year-old group are mothers. And there is a social gap: the richest quintile has an average of 0.9 children while the poorest has 3.0 on average.

While the ENCOVI registers a drop in mothers aged 15-19 from 27% in 2021 to 14% in 2023, coordinator Anitza Freitez said that these results must be taken “with caution” due to such a sharp drop. The study also found that women who become young mothers attend school less and have fewer years of study.

Looking for the American dream

Xenophobia and economic and political crises in neighboring countries are redirecting migration flows into the United States. For example, the migratory flow to Peru fell from the previous years but increased to the United States.

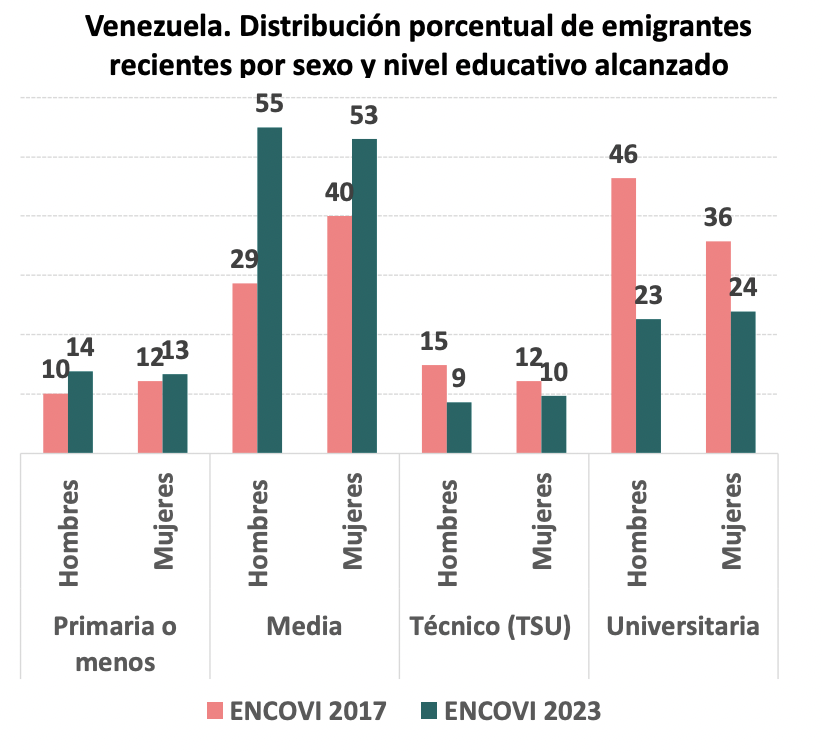

More importantly, the age groups of migrants changed: the group of 30-49 years old now exceeds those that are 15-24 years old, the predominant group until 2021. Also, educational levels have changed. There are now more migrants with secondary education (29% to 55% in men) but fewer with university degrees (from 46% to 23% in men) compared to 2017. Transfers of remittance have also fallen from 64% in 2021 to 56% in 2023.

An unequal country

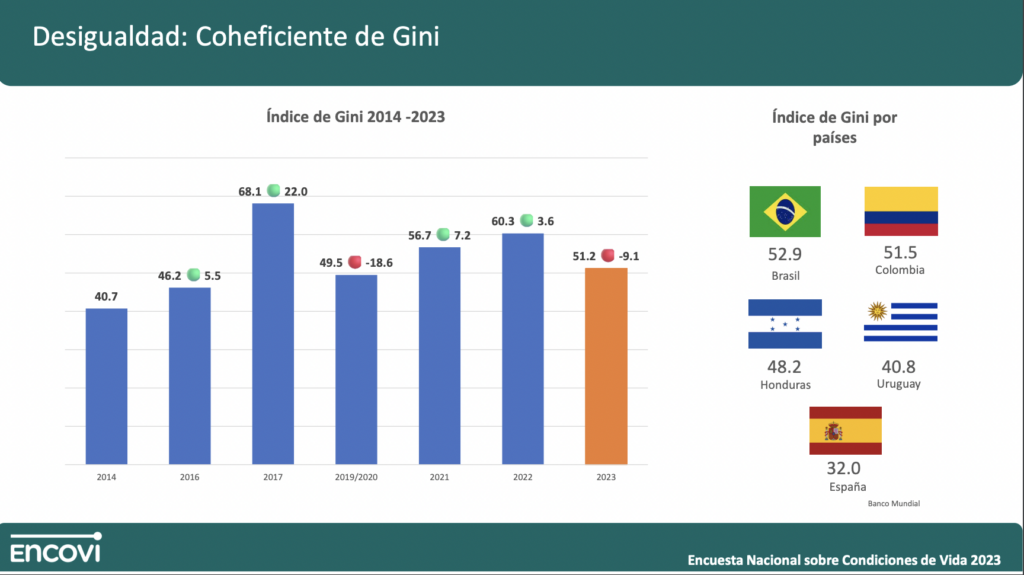

After the fall in income poverty in 2022, the rate has remained almost intact in 2023: 82.8% of households suffer from income poverty. Of the total, 50.5% suffer from extreme income poverty. Yet, inequality –which had risen recently– saw a decrease: although a notable gap in income remains between the richest and poorest deciles, the Gini coefficient –which measures inequality– registered a drop of 9 points since 2022 (from 60.3 to 51.2), now below Colombia and Brazil.

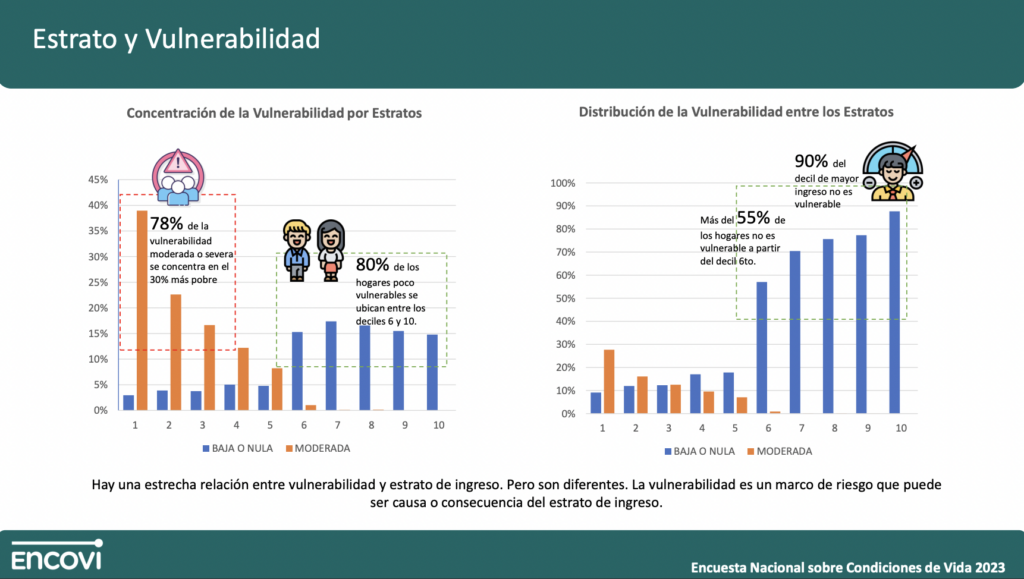

Similarly, vulnerability –an ENCOVI measure that includes health services, health and food, income, education, housing, social protection and employment– has stabilized in 2023 after a decrease in 2022. This opens the door to chronic vulnerability that requires public policies. In fact, 78% of moderate or severe vulnerability occurs in the poorest 30% of the population while 80% of the registries of low or no vulnerability occurs in the five richest deciles. More than 55% of households from the sixth decile onwards do not register vulnerability.

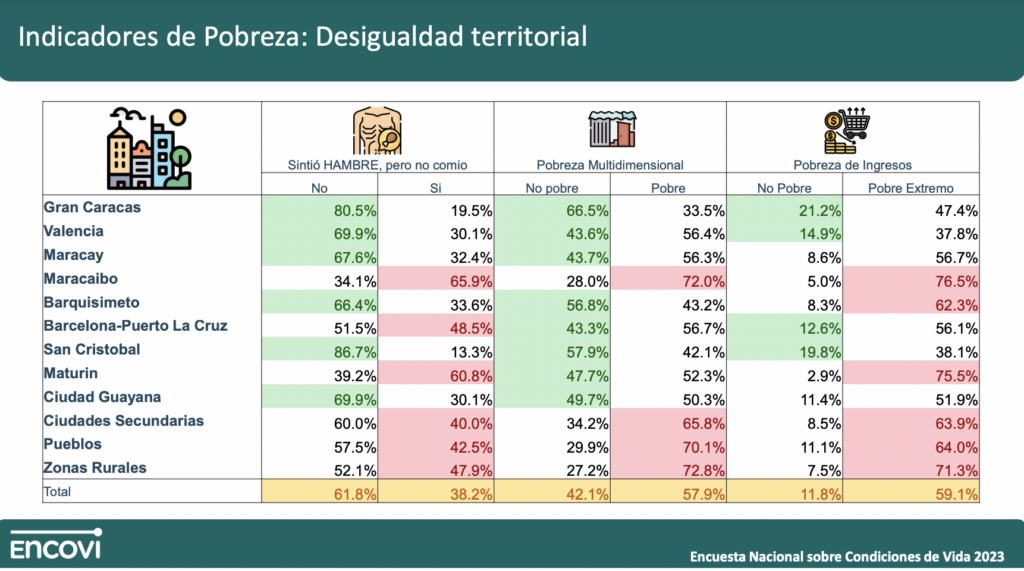

Territorial inequality is also notorious: while only 19.5% of the inhabitants of Greater Caracas say they cannot eat even if they feel hungry, the percentage rises to 65.9% in Maracaibo. Similarly, multidimensional poverty covers 33.5% of Caraqueños and 72% of Marabinos: more than double the rate of Caracas. The same happens with extreme poverty: 47.4% vs. 76.5%.

In fact, while San Cristobal shows indicators even higher than those of Greater Caracas, the former oil hubs are now the most vulnerable areas: Maracaibo, Maturin and Barcelona-Puerto La Cruz.

ENCOVI, for the first time, also measured internal migration. According to the survey, 2.1 million Venezuelans have migrated internally between 2018 and 2023. But only 2% say that they did so because of public services. 80% said they did it for personal reasons. Migration flowed mostly towards Caracas, Miranda and Carabobo but also from Zulia to Mérida and Guárico to Barinas.

No country for working men

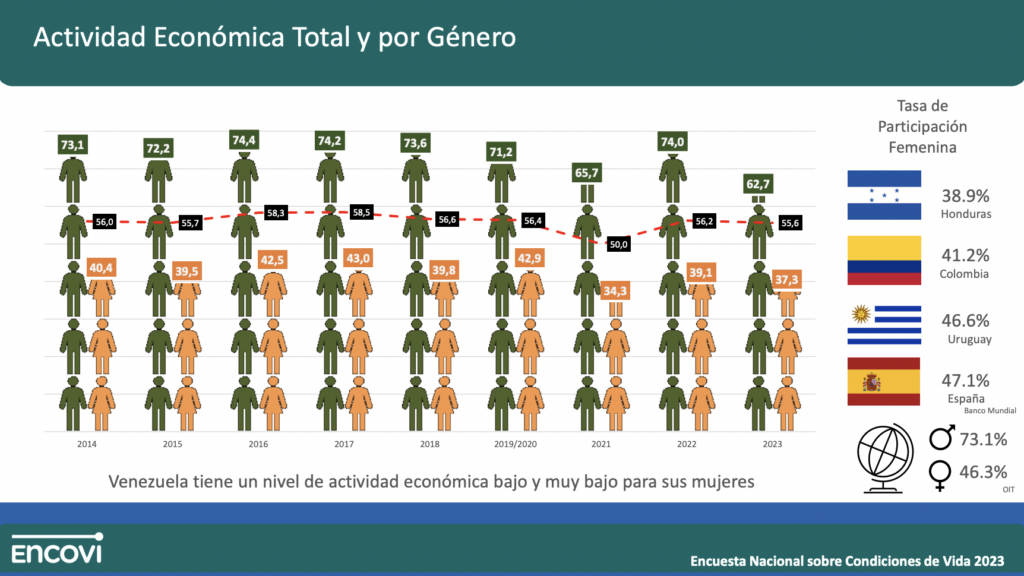

Only 62.7% of men in Venezuela are economically active, lower than the 74% of 2022 (which exceeded 2014 levels) and below the world average. The female rate is 37.3%, lower than the world average and other countries in the region (in Colombia it is 41.2 %)

In fact, only 4.7 out of every 10 people in extreme poverty are in the labor force. A number similar to that of the poorest quintile. Meanwhile, nearly every 7 in 10 people in the richest quintile are part of the labor force.

Similarly, those working in the public sector went from 35.8% of the workforce in 2014 to just 20% in 2023 (below the 20% of the private sector and 48.3% of the “self-employed”). This latter group has grown as the private and public sector workforce decreases.

With such a dire situation, government cash handouts and food bags remain a crucial role. In fact, 79.5% of households have received at least one bonus in the last 12 months, an increase from 71% in 2022. Of those who received one, 44.1% say they receive a bonus monthly. The average value of these bonuses is $19.6 per month. Meanwhile, 7.2 million households (83.1) received CLAP boxes.

Yet, Venezuela is so impoverished that the ENCOVI estimates that 40% of the 2023 oil income would be needed in bonuses so that households can leave extreme poverty.

There are some good news. Food insecurity continues to decline. Only 12% (against 34% in 2020) say they went without eating all day and 32% (down from almost 50% in 2020) felt hungry but did not eat. The only increase since 2022, while important, is of those who “ran out of food” (45.8%). An effect of high prices?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate