State-Enabled Illicit Trades Represent More Than a Quarter of Venezuela’s Economy

According to a new study by Transparency’s local chapter and Ecoanalítica, illicit economies made up 15,67% of Venezuela’s GDP in 2022. Its profits equal half of those of all exports, ushering a criminal bonanza that includes slavery

On December 10th, around six hours later than expected and almost at dawn, Dominican bachata superstar Romeo Santos began his concert in Caracas. “This is irresponsible and a disrespect to you, the public”, he said on stage, blaming the production company. His fans had waited for hours in La Carlota, a military airbase in east Caracas that is occasionally used for concerts. The next day, General Attorney Tarek W. Saab opened an investigation against production company Panteras Entertainment: he calmy explained that the company was run by Juan Carlos Araujo, an imprisoned businessman and drug trafficker, in complicity with Argenis Guerra – director of the El Rodeo prison outside Caracas.

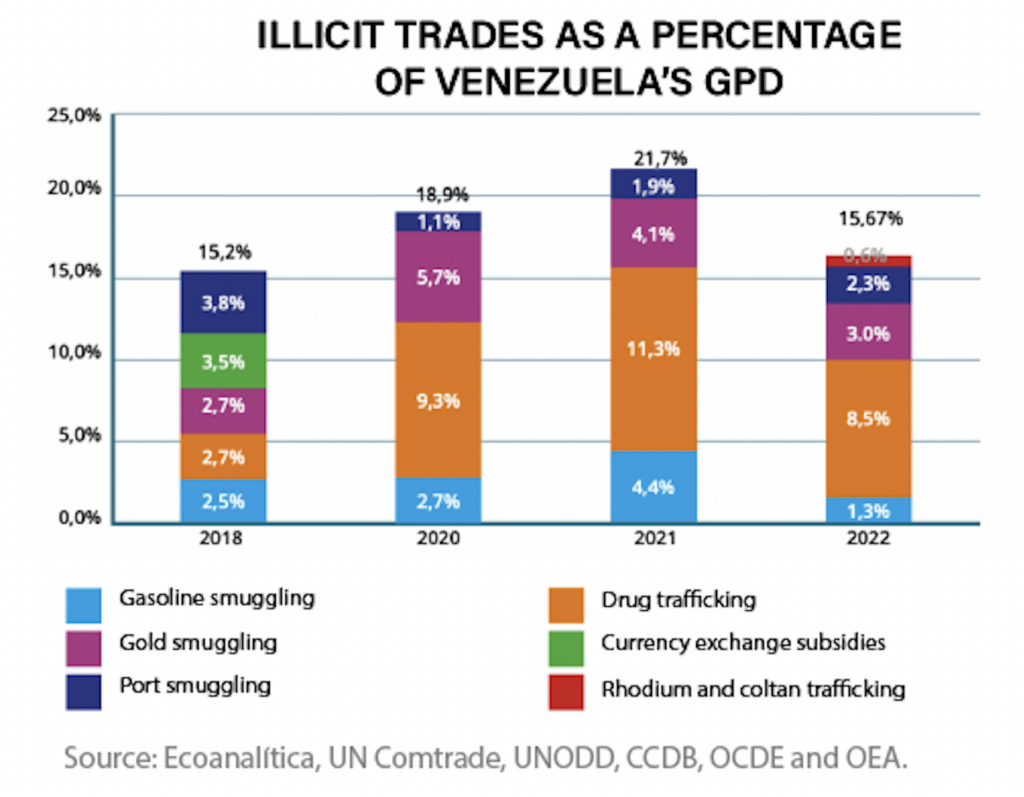

An inmate organizing concerts with international singers in a military airbase shouldn’t be surprising in a country where illicit economies make up 15,67% of the GDP, or $9.4 billion, in 2022, according to a recent study by Transparency International’s local chapter and research and consulting firm Ecoanalítica.

While the lukewarm formal economy has reduced its share of the GDP in comparison to 2021, when the study was first carried out, the amount produced by illicit economies has barely changed. For the new study, the trafficking of gold, rhodium, coltan (all three total $2.1 billion), drugs ($5.1 billion) and fuel ($760 million) was studied as well as port smuggling ($1.3 billion).

The estimates derive from documentary consultation of national and international secondary sources, visits and face-to-face interviews in regions of the country in which these crimes are most registered and information from people who work within state institutions. For drug trafficking estimates, the report used 2022 seizure reports, estimates from the US’ Consolidated Counterdrug Database and an average retail sale price of destination markets for Venezuelan drug exports.

Among the findings, there is a major decrease from 2021 in the rent produced by fuel trafficking and a noticeable increase in the amount of money produced by drug trafficking and port smuggling. While gold trafficking is a bit less profitable than before, production rose 20% due to more formal ventures.

According to Asdrúbal Oliveros, director of Ecoanalítica, the share of illicit economies in Venezuela has grown since 2016 because of the collapse of Venezuela’s hydrocarbons industry. “Oil is the main producer of wealth in the country”, he says, “A whole source of political and economic clientelism derived from it and it obviously collapsed, and it had to search for alternative sources.” According to Oliveros, the “institutional destruction” generated by autocratization in Venezuela and the international sanctions have fed “a parallel structure”. “Nicolás Maduro had to allow access to other sources of income to powerful political, military and paramilitary groups in order to sustain his coalition and avoid a breakdown”, he says.

The impact of illicit trades in Venezuela’s economy should not be minimized. In the study, Ecoanalítica found that profits from illicit trades equal 56,4% of Venezuelan exports of goods, 56,3% of total governmental income and 77,8% of all imports.

The Mafia State

How did illicit economies become this powerful in Venezuela? According to Transparency, there is nowadays a “symbiotic relationship” between criminal actors and state institutions as the interdependence between organized crime and the political and economic system has made borders “tenuous” and a sort “political-bureaucratic-economic-criminal corporation” crystallizes. “The state is silent, the state cooperates, or the state facilitates”, says Mercedes de Freitas, Transparencia Venezuela’s executive director.

For example, de Freitas explains, all sorts of security forces actively participate in gold trafficking in the Orinoco Mining Arc: ranging from the Army and the National Guard, through intelligence agencies DIGECIM and Sebin, to the National Police and both regional and municipal police departments in Bolívar state. But the participation of state actors in the gold trade doesn’t end there: there’s also the Ministry of the Economy, the Ministry of Mining and the Venezuelan Corporation of Mining, which is led by a former minister. “Only those who are close to power have the privilege to exploit gold”, she says.

Recently, for example, investigative journalism site Armando.Info—with the massive leak of documents from the Colombian Prosecutor’s Office, complemented by other reports and dozens of interviews—exposed the internal functioning of the Cartel of the Suns, a drug cartel within the Venezuela Armed Force in which high-ranking officials of the government participate.

In fact, according to Transparency’s report, Venezuelan criminal networks have an elevated level of “criminal resilience”, the capacity to survive despite a change in governmental actors, and can expand to different areas in Venezuela and abroad. Most importantly, these networks are supported by or include “grey agents”, which act from within formal organizations such as State institutions. According to the report, gray agents have coopted the judiciary to favor criminal interests and even state security forces.

But “facilitators are important”, de Freitas says. For example, to create the companies through which the money will be deposited abroad, to organize audits or to find tax havens to create ghost companies. “Gray agents also facilitate laundering money from drug or gold trafficking, through the purchase of real estate, company or bank stocks, casinos or production companies.” All this process implies the participation of law firms and companies related to audits, finances, insurance, real estate and stock trading. Trickle down crime?

The impact of illicit trades in Venezuela’s economy should not be minimized. In the study, Ecoanalítica found that profits from illicit trades equal 56,4% of Venezuelan exports of goods, 56,3% of total governmental income and 77,8% of all imports.

According to the report, the government lacks a real program to control illicit trades. It has been opaque regarding details on its highly-publicized anti-crime operations. It announces crackdown on gangs but never mentions its leaders, and uses generic terms or neologisms when mentioning criminal actors (“Tancol”, for example, for “Colombian armed narco-terrorists”) and blames foreign actors: for example, when Chavista officials were found out to participate in drug trafficking, the General Attorney described it as “the Colombianization of institutional life in Venezuela.”

The New Dynamic of Venezuela’s Gold Fever

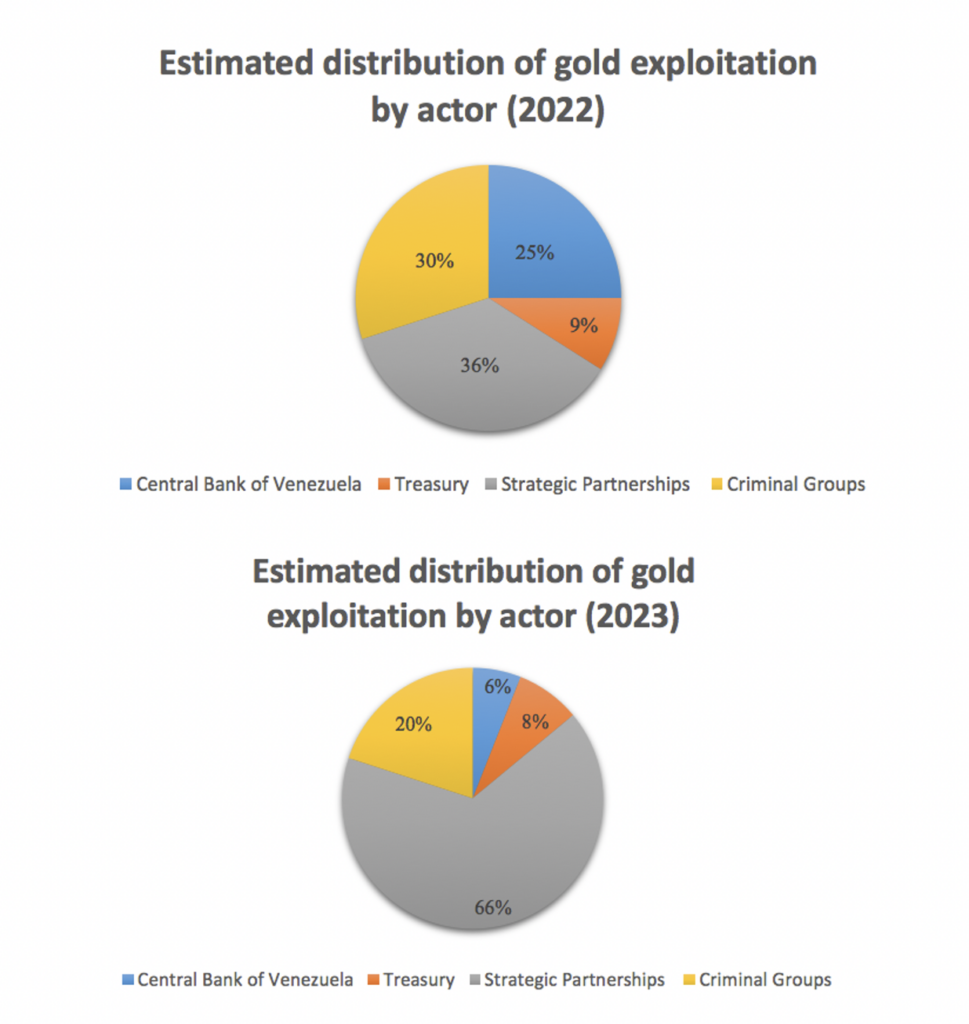

Transparency’s study also shows how the power dynamics in the Orinoco Mining Arc have changed in the last year. According to Oliveros, gold production is “the most significant revenue [for the state] after oil” but it has ushered “an illicit economy that involves [local] communities” in southern Venezuela, generating “the strongest degradation of the illicit economies in Venezuela.” This economic dynamic is defined by three groups: the state through, its companies and the Central Bank of Venezuela; military and paramilitary groups that exploit the mines; and private businessmen and cronies who work with the state through “strategic partnerships”, a recently created legal figure in the gold sector in which private companies or cronies establish business alliances with state-owned companies. Unlike historical joint ventures, which have vanished in the Mining Arc since 2020, the state isn’t necessarily the main shareholder. “In the few documents we have found, the state has a share of only 20%”, de Freitas says.

Nevertheless, the state is making a comeback through the strategic partnerships, which doubled in 2022. According to the report, in 2022 around 25% of Venezuelan gold production was received by the Central Bank of Venezuela (between 9,5 and 11 tons or between $570 million and $660 million), 9% to the National Treasury (around 3,37 and 4,06 tons or $195 million and $243 million), 36% to “strategic alliances” between private companies and the Venezuelan Mining Corporation (around 13,5 and 16,2 tons or between $810 million and $972 million) and 30% went to criminal gangs, guerrillas and other illicit non-state actors (between 11,25 and 13,5 tons or $675 and $810 million).

Nevertheless, the study estimates that in 2023 66% of the revenue from gold production was received by strategic alliances, while 8% went to national bank accounts, 5% to the Central Bank to authorize exports due to its limited purchasing power and 20% to criminal gangs which are losing more ground to military operations. “Gold is no longer in control of the state”, de Freitas says, “for the central government it’s attractive to promote the creation of more strategic alliances to produce more gold.” In fact, the study estimates that gold production in the Mining Arc could have risen from 20% to 30% by the end of 2023, due to the strategic partnerships, which could mean more than 45 tons more per year, and over $3 billion.

According to de Freitas, foreign companies are not operating in the Mining Arc –with the possible exception of an Iranian company. The study also added estimates of coltan and rhodium trafficking, despite the limited information, which could generate at least $750,000 annually and $350 million annually, respectively, to the criminal groups exploiting it in southern Venezuela.

Criminal Balkanization

The study also improved the methodology used to estimate the revenues generated by drug trafficking, as Venezuela is a transit country through which Colombian production is exported internationally. According to the report, drug trafficking in Venezuela generated $5.1 billion in 2022 alone. This illicit economy, the study says, is dominated by national and international cartels as well as Colombian guerrilla groups such as the dissident FARC groups and the ELN. Most of these groups operate in border areas, like Northern Zulia and Guayana. The Mexican Sinaloa cartel, sources assure, operates in the Perijá mountain range, for example. “There’s a town called San Felipe but people call it Sinaloa due to the Mexicans”, one source said. A similar situation happens in the paradisal Paria peninsula in Sucre, where drug cartels have taken over entire towns and areas. “Everything, absolutely everything, is decided by criminal groups”, a security official assured Transparency.

Venezuela’s Slave Economy

The new study also included another profitable illicit economy booming in Venezuela: modern slavery, ranging from human trafficking in Sucre for commercial sexual exploitation in the Caribbean to modern slavery in the Mining Arc. “We are impressed by how human trafficking has increased”, de Freitas says. While the researchers couldn’t estimate its share in the economy, they did find unsettling stories showing its profitability: millions of dollars, for example, for ten underage Venezuelan girls to be exploited by Chinese mobsters in Trinidad and Tobago. In the islands, for example, a Venezuelan baby girl can be sold for $75,000, the study found out.

In fact, the study quotes a monitoring by NGO Mulier, which found that between 2018 and 2022 the number of Venezuelan women saved from trafficking networks rose from 372 to 1,390: an impressive increase, but only a fraction of the actual numbers involved in the whole human trafficking industry. According to de Freitas, Venezuelan women –alongside networks of ketamine trafficking– are being increasingly trafficked to other South American countries.

Entire communities, says the head of Transparency International Venezuela, end up depending on the criminal gangs which provide stability and “the illusion of improvement”: the mining town of Las Claritas, for example, has one of the best hospitals of Bolívar state and the only one with a crematorium. In Semprún and Catatumbo, near the northern Colombian border, growing coca is the only revenue for some communities despite the skin allergy it can cause on coca pickers. Soon, de Freitas says, people start to operate in social, cultural, and labor groups that are distinct from those of formal societies within the rule of law.

“There is labor and child exploitation as well as human trafficking”, Oliveros says, “Illicit economies are creating a paralegal structure outside the state where labor rules, environmental protection, laws protecting children and women and the entire legal framework that protects vulnerable population isn’t being applied in whole areas [of Venezuela].”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate