A Custom-Made Anti-Primaries “Opposition”

Chavista-controlled media and institutions are pushing an anti-primaries narrative through nominally opposition figures, coming hands clean and validating their attacks

In July, María Carolina Uzcátegui quit her position as vice president of the National Commission of Primaries, the organization in charge of organizing the opposition’s primaries in October. She cited supposed logistical problems originating from the Commission’s decision to “self-manage” the primaries without the National Electoral Council (CNE) and talked about “interests” hijacking the primaries to turn them into “personal projects.”

But, soon thereafter, what seemed like a political and logistical critique of the primaries became an orchestrated campaign. First, Uzcátegui gave a press conference in September criticizing the technical capabilities of the Commission to organize the primaries and then went on a television and radio tour to air her criticism. Her critics soon resurfaced Uzcátegui’s past flirts with “alternative opposition” parties, including being a parliamentary candidate in 2020 for Unión y Progreso (the party of Eduardo Fernández, a former copeyano who is now rabidly anti-primaries) and being a speaker at a feminist event by Cambiemos, the party of Timoteo Zambrano, who leads the 2020 National Assembly’s committee in charge of writing the controversial anti-NGO law.

Uzcátegui then started to post well-edited videos with epic music, including one criticizing opposition frontrunner María Corina Machado, and even announced her participation in the first episode of a podcast by Globovisión: a former opposition channel bought by Chavista crony Raúl Gorrín, who recently called independent journalists’ “reptiles” and is sought by the United States for corruption. Uzcátegui’s intentions now seemed more malicious.

“Podcast Globovisión’s” first episode, focused on the primaries and hosted by radical-to-Chavista-friendly journalist Kiko Bautista, included other two controversial figures: Indira Urbaneja, a Chavista political analyst who has rabidly opposed the primaries and has even sought to defame some of the Commission’s members, and former San Cristóbal mayor Daniel Ceballos. Nightmare blunt rotation.

The latter, formerly a member of Leopoldo López’s party Voluntad Popular, was arrested in 2014 for his role in that year’s protests. He was transferred to the infamous Helicoide prison and released in 2018. Since then, he did a full change in direction and became a critic of the mainstream opposition, even joining the version of Voluntad Popular created through an intervention by the Chavista-controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ).

It was clear that Chavista-aligned media were pushing an anti-primaries narrative through nominally opposition figures, associated with “systemic opposition” parties—some even linked to judicial interventions. With this strategy, Chavista figures could come hands clean and validate their attacks on the primaries through supposedly intra-opposition criticism.

In fact, some of these visions and affirmations were repeatedly aired and magnified in Chavista hardliner Diosdado Cabello’s TV show El Mazo Dando. Similarly, some of these figures repeated Cabello’s words: for example, soon after Cabello affirmed that there were “massive resignations” in the Commission’s regional boards, María Carolina Uzcátegui repeated the same comments in a radio interview. Yet, according to sources from the Commission, only two out of 120 members had resigned. The Commission also warned of a Chavista attempt to do an “alacrán operation” and hijack the regional juntas by buying off its members.

Errand Boys In The Institutions

But the strategy of creating a custom-made opposition to attack the primaries and sow doubts hasn’t been limited to communication campaigns. Nominally opposition figures have also tried to legally butcher the primaries and its candidates through the courts and the Comptroller’s Office.

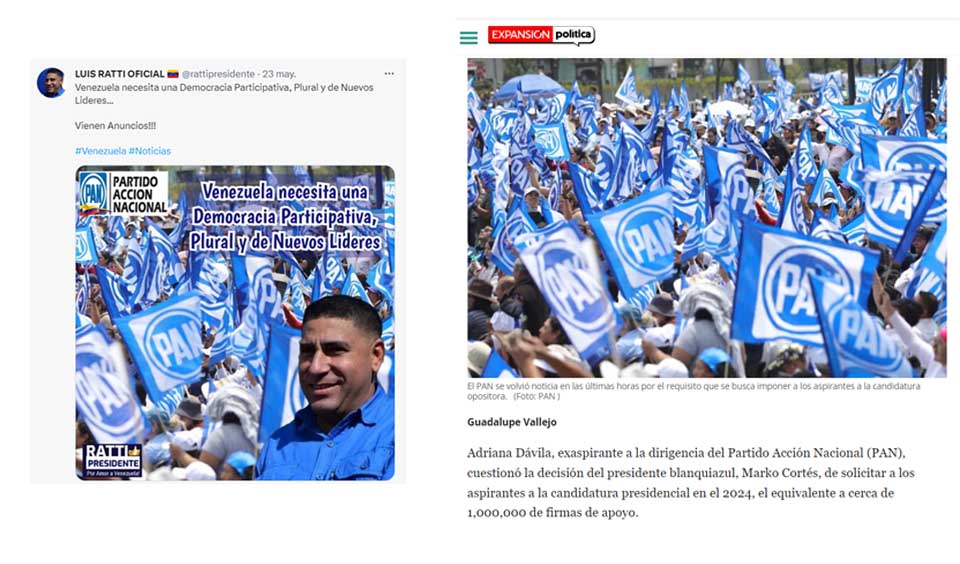

The most notable of these figures is Luis Ratti, who journalist Oscar Medina described as “haughty and loud errand boy invented by Chavismo.” Ratti appeared out of the blue to proclaim himself as an independent opposition candidate, despite his past as president of the Hugo Chávez Bolivarian Front in 2016. The whole theatricality of the stunt is spearheaded by his legally inexistent party: PAN, which blatantly copied the name, logo, and social media content of the homonymous Mexican conservative party.

In May, Ratti rose to political fame when he went to the TSJ to demand a judicial intervention of the primaries and the naming of a new puppet National Commission of Primaries to fight the “kidnapping of the opposition” by people like Machado and Henrique Capriles. Three months later, alleging that a Machado victory would usher in subversive violence, Ratti demanded the candidate’s apprehension and called the primaries’ organizers “a putschist group.” Ratti then went on to ask for bans on running for office for a plethora of candidates, launched a dirty communicational war against Machado and even returned to the TSJ to ask once again for an intervention to end the primaries. Surprisingly, not much happened. Ratti, alone and rambling, went from malign errand boy to loca del muelle de San Blas.

It was clear that Chavista-aligned media were pushing an anti-primaries narrative through nominally opposition figures, associated with “systemic opposition” parties—some even linked to judicial interventions. With this strategy, Chavista figures could come hands clean and validate their attacks on the primaries through supposedly intra-opposition criticism.

His “colleague” Luis Brito, who harshly criticized him, had more success. A former Primero Justicia (PJ) lawmaker involved in the operación alacrán corruption scandal, in which Maduro crony Alex Saab allegedly paid opposition lawmakers to lobby for him, Brito now leads a TSJ-created doppelganger of PJ named Primero Venezuela. Brito went to the Comptroller’s Office to ask for a “clarification” regarding María Corina Machado’s legal status. The Office soon after replied, retroactively extending an expired ban from running for office (inhabilitación), and now blaming Machado of promoting a foreign intervention, crippling the economy through her support of sanctions, and somehow taking the medicine away from 60.000 HIV patients.

Through the stunt, a nominally opposition politician allowed the Chavistas to ban increasingly popular Machado and try to put out her electoral flame without having to get their hands dirty. Meanwhile, Luis Brito leads his own presidential campaign outside the primaries and the mainstream opposition infights due to the Comptroller’s decision.

“Alternative” Candidates

Brito is not the only nominally “opposition” anti-primaries politician running for president outside the primaries. Others, like Antonio Ecarri and comedian Benjamín Rausseo, “Er Conde del Guácharo,” are doing the same. Without daring to run in them, Ecarri has accused the primaries of “excluding” factors outside the G4 group of opposition primaries and has even pushed the conspiracy theory of an electoral arrangement between the primaries’ organizers and the Maduro regime. Yet, even in 2020, Ecarri and his Alianza del Lápiz party were part of the Guaidó-led opposition coalition.

Like Ecarri and Rausseo, there is a rising genre of nominally opposition politicians announcing candidacies outside the primaries: like those of the TSJ-created versions of Acción Democrática and Copei.

Similarly, Er Conde del Guácharo—who allegedly became close to Juan Barreto, a dissident Chavista and former mayor of Caracas during the Chávez heydays—accused the primaries of representing “a sector of the opposition” when he announced he was retiring from them.

Like Ecarri and Rausseo, there is a rising genre of nominally opposition politicians announcing candidacies outside the primaries: like those of the TSJ-created versions of Acción Democrática and Copei.

In the past year, many of these parties and coalitions –including Lápiz and the Alianza Democática coalition, which harbored the intervened AD and Copei as well as the parties that now support Ecarri– were actively pushed by the Maduro regime: for example, through the creation of performative negotiation tables with these sectors or Jorge Rodríguez’s insistence of having them included in the Mexico negotiations. Similarly, the aforementioned Eduardo Fernández –an anti-primaries pundit like others in his new party, which went against the Unitary Platform in most states during the 2021 elections– was the first politician to openly call for a “consensus candidate” and has mentioned the possibility of him being it. Similarly, Fuerza Vecinal is now calling for the suspension of the primaries and for the sectors of the opposition to decide on a joint candidacy.

In fact, some forces within the Unitary Platform seem to be pushing for a consensus candidate outside a primary that has revealed the rejection opposition voters are projecting towards the party establishment. For example, Zulia governor Manuel Rosales isn’t running in the primaries. But he’s revealed recently his “presidential aspirations” aren’t dead (despite suspicions, Henrique Capriles—in his APEX press conference—said he won’t support a Rosales candidacy in 2024). This strategy would seek to halt the collapse of the opposition establishment and push for a “viable” option… defined by party leaderships sweeping aside the electorate’s will.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate