Making Cars in Venezuela: From 172,000 Units per Year to One

Ever wonder why a 10-year-old used car could cost ove $20k in Venezuela? Here's part of the answer

Mercedes Benz assembly line, Los Montones, Anzoátegui (08/08/1976)

Photo: Robert Madden / National Geographic

In the August 1976 issue of the National Geographic magazine, an article about the Venezuelan economy shows the picture of two workers installing a frontal grill on a Mercedes Benz W116 sedan. This car was sold at the time at 145,000 bolivars, about $ 34,000 at the exchange rate of 1976 (4,30 Bs / $). That year, 1,487 units of the Mercedes Benz W116, in its 280 and 350 versions, were assembled at the plant in Barcelona, Anzoategui state. However, there was a waiting list in the local Mercedes Benz dealers. That year, a total of 164,608 cars and trucks were assembled in Venezuela.

The car and truck assembly plants had started in the country back in 1944—yes, during WW2—with General Motors Interamericana, set up by General Motors Corporation (GMC), who first established a warehouse in San Martin, Caracas, and opened another plant nearby in 1948. Parts and subassemblies were shipped from the US and Canada.

The first assembled unit in Venezuelan soil was a Chevrolet pickup truck.

In 1950, Chrysler and local entrepreneurs like the Phelps family opened an assembly plant in Los Cortijos (Ensamblaje Venezolano, S.A.), which operated until 1965, when it was relocated to Valencia with different owners and designation.

Expanding a local cluster

The main reason for bringing cars and trucks disassembled in those years was tax discount incentives and local job openings from the receiving country (Venezuela in this case) and additional sales of semi-complete units (and later sale of spare parts and service) from the exporting country (United States in this case).

Later, in the early 1960s, the Venezuelan government invited companies from the US and Europe to set up additional assembly plants, with regulations that included adding local content in the form of components manufactured in Venezuela. The assembly plants were required to help establish these local part manufacturers, with assistance of their supplier chains in the US and Europe. Tires, batteries, windshields and other glass components, upholstery and exhaust systems, among others, were the first lines to be developed in Venezuela. By 1964, the local content percentage, in weight, was around 19%.

Those assembly plants established in the 1960s and 1970s belonged to American Motors, Ford de Venezuela, FIAT, Renault, Mack de Venezuela, Mercedes Benz, and other local subsidiaries of transnational companies. Goodyear and Firestone also built factories to supply tires for those car and truck assembly plants and to replenish the hundreds of thousands of cars and trucks already riding the country’s roads. Other companies produced shock-absorber and suspension parts (coil and leaf springs), differentials, wheels, drum and disk brakes, electrical parts, copper brass and aluminum radiators, air conditioning components, electrical parts such as alternators, starter engines, chassis parts and some sheet metal parts.

It was a proper industrial cluster, and the universities and technical schools started to train a professional class to take advantage of the jobs it created.

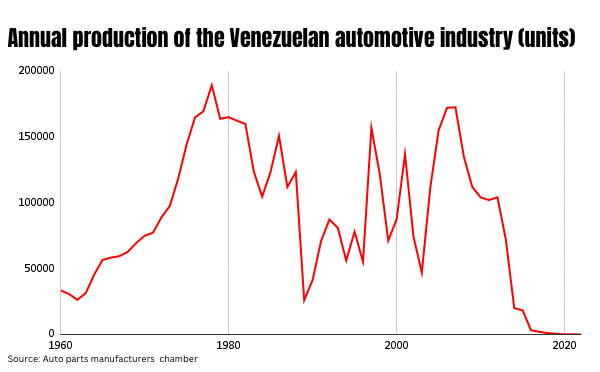

During the 1970s oil boom, local production rose to reach a record in 1978: 180,687 vehicles assembled in one year.

Then the 1983 “Black Friday” came.

Meddling with currency and tariffs

During the Herrera and Lusinchi administrations, the two-tier currency exchange rate system (the infamous Recadi) required the assembly plants and local suppliers which imported components to request subsidized currency to the government.

The subsequent red tape and the bolivar devaluation ended up restricting production and sales. Car and truck prices rose in proportion to the exchange rate, which was no longer 4,30 bs / USD. Production plateaued around 123,000 vehicles per year—peaking 150,637 units in 1986—but in 1989 it dropped drastically, to 25,962 units.

Why? The second Perez administration reduced import tariffs for finished vehicles, and sales of imported cars made a dent in the market. It would not be until 2007, approaching the oil boom of the Chavez era, when sales of locally assembled cars would rise again to a peak of 172,361 units.

Local part manufacturers had some good years between 1986 and 1996, when tax incentives and local raw material discounts (such as primary aluminum) would make them competitive for exporting part of their production to Latin American neighbors. Manufacturer Rualca, for instance, exported aluminum wheels for the 91-94 Chevrolet Blazer and Chrysler Cherokees Jeeps in the USA. Faaca and its joint venture Delfa exported AC units used in the Chevrolet Monza to Brazil between 1988 and 1994, and later Radiadores Infra would export radiators for the Chevrolet Corsas manufactured by General Motors do Brazil in 95-02. Danaven would also export differentials to Jeep in the US.

In 2006 the Venezuelan assembly plants managed to export 24,000 finished vehicles to the Andean Community market.

However, from almost 200,000 in 2007, we went to only eight units assembled in 2021. What happened in the meantime?

Killing an entire industry

This is the part of this story that must be fresh in our minds. Ideology got in the way, both in domestic economic policy and in the local consequences of the chavista governments foreign alliances. The oil-funded consumer boom around 2010 took us from an explosion of (subsidized) local production and a program to democratize access to new vehicles, to the arrival of Chinese and Iranian imported cars, the practice of denouncing international trade agreements such as the Andean Pact, and the eventual disparition of foreign currency after the disastrous outcome of the Cadivi years.

GMV ceased operations in May 2017, after being sued by a dealer for “unfair practices”. Chrysler de Venezuela shut down in March 2018, due to lack of “Raw material.” Toyota de Venezuela still sells vehicles in the country, but after importing them from Japan, Thailand, Brazil, and Argentina. And Mitsubishi, who was assembling vehicles at the same Barcelona plant where Mercedes was in 1976, ceased operations in 2009.

Today, the facilities of what was a mighty industry may not look too bad from the outside. Inside the plants, it’s another story: empty offices, abandoned equipment, silence and dust.

Will the Venezuelan automotive and auto parts industry resurge from its ashes? Just like PDVSA, it would need personnel, functional infrastructure, regulatory protection and massive local and foreign investment, especially from the GM or Ford headquarters, to update the Venezuelan plants to produce the more advance models of today. The bones of that industry are still here. Something to keep in mind just in case.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate