¿Y tú qué propones?: 20 Years of Opposition Proposals

Over 20 years of hearing that the Venezuelan opposition doesn't have a counter proposal to chavismo. Tony dives into the past to see whether this is true

Image from Leopoldo´s "La mayoría para qué" campaign

Despite having the tacit or direct support of most of Venezuela’s organized civil society, professional guilds and academies, the Venezuelan opposition—and its mostly ideologically-empty parties—has barely produced an intellectual-politician or writer-politician. There is no modern-day Plan de Barranquilla or a modern-day Rómulo Betancourt writing Venezuela, política y petróleo or a modern-day Rafael Caldera writing a biography of Andrés Bello or books on Christian Democracy and the nationalization of oil (perhaps Henry Ramos Allup and Leópoldo López, with books on liberalism and energy policy, could be spared?). Our opposition doesn’t know how to use commas in its cliché-full communiques, its recent debates have been described as “grotesque” and “lacking arguments” and it’s even losing the communicational battle on TikTok (and let’s not talk about the Unity Platform’s boring-to-death Instagram, the social media Venezuelans use the most to inform themselves on politics according to recent polls by More Consulting). In fact, Acción Democrática’s pre-candidate—representing one of the country’s oldest and most historically influential parties—recently confused xenophobia with both homophobia and misogyny. So, in such a state of intellectual sterility: what were the proposals of the opposition?

El Carmonazo: Reset the Revolution

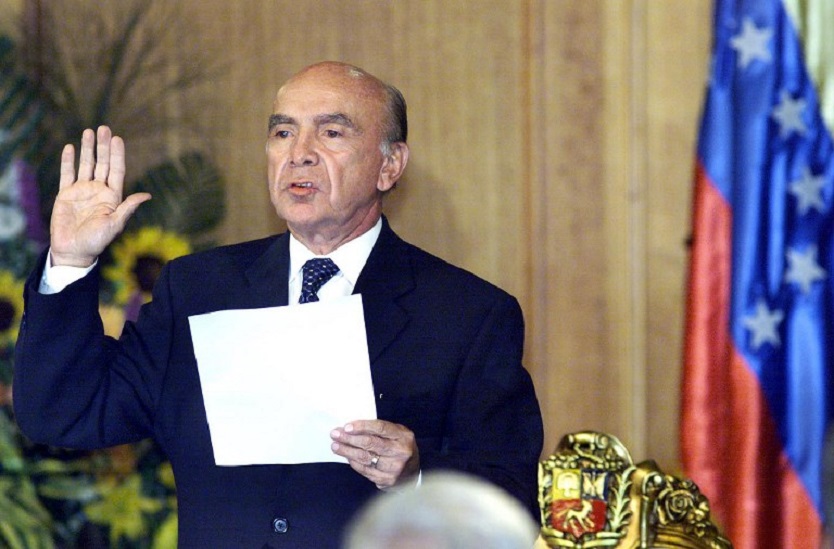

The Carmona oath – April 12th 2002 at the Miraflores Palace

Photo: AFP PHOTO/RODRIGO ARANGUA

The first real approach of the opposition to power—at a moment when it was reacting to Chávez’s push for revolutionary changes—was in early 2002: first when it pushed against Chávez’s 49 law package and then when Pedro Carmona Estanga, the president of Venezuela’s main business guild, took “power” (by being able to hold a press conference in Miraflores) after Chávez was briefly deposed on April 11th.

The Carmona Decree was a reset of the revolution: it illegally named a new gabinet and suspended all National Assembly congressmen, Supreme Tribunal of Justice magistrates, members of the Electoral Council, the Ombudsman and the General Attorney. Most importantly, it called for a new congress with constituent powers to modify the 1999 Constitution and removed the word “Bolivarian” from the country’s name. Carmona’s proposal, if we can call it that, was wiping the hard drive back to 1999.

Rosales: Democratic Chavismo?

When the opposition gave another chance to elections in 2006, Manuel Rosales was chosen as the consensus candidate. As such, his proposal was vague: based on the opposition’s general premise of re-democratizing institutions to ensure their independence, depoliticizing the Armed Forces and respecting private property to attract foreign investment. Rosales also proposed handing school supplies, decentralizing public education and handing college scholarships through his proposed “Arturo Uslar Pietri” program. Interestingly, despite being anti-Chavismo’s candidate against Chávez’s rising authoritarianism, he also proposed fairly authoritarian proposals like a National Council of Justice and Security headed by himself and a National Police supported by a “secret system of investigations and rewards” (Chávez would end up creating a Bolivarian National Police—eventually known for its extrajudicial executions- three years later).

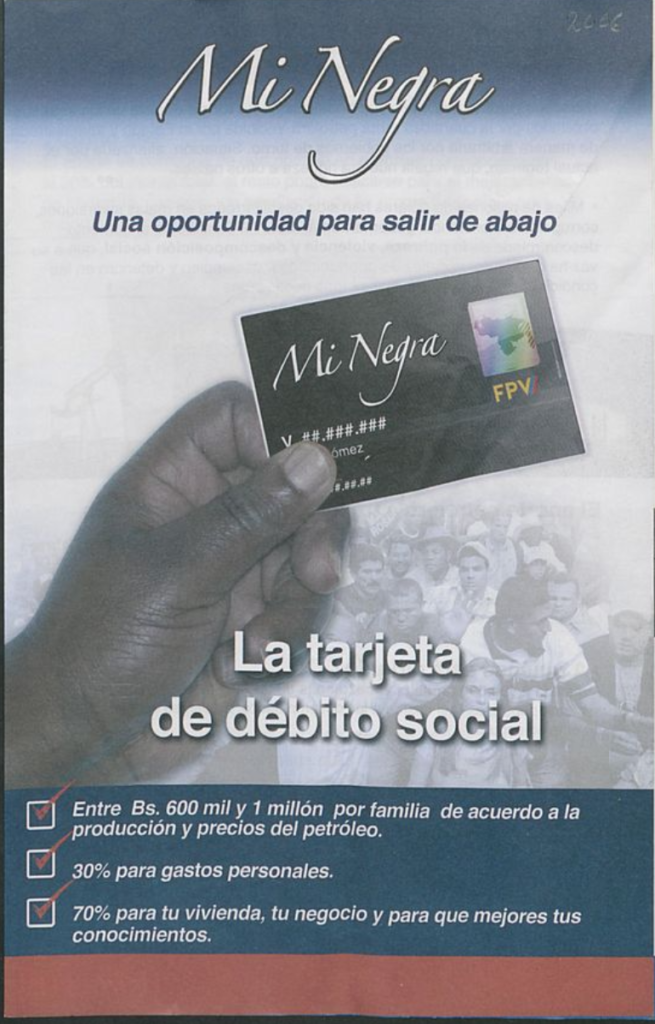

Nevertheless, Rosales’ main proposal was the Mi Negra card: a debit card that would get money directly from Venezuela’s oil revenue, allocating 30% for personal expenses and 70% for basic needs. In fact, the Mi Negra model is probably Rosales’ longest lasting idea. It’s been adapted in a never-ending parade of failed proposals: Henri Falcón’s “tarjeta solidaria” in 2018, a proposal in Juan Guaidó’s 2019 Plan País, Leocenis García’s “El Negro” card in 2021, and Antonio Ecarri’s 2022 “Mi Barril” card. In 2016, Nicolás Maduro even announced a “Tarjeta Misión Socialista” that would allocate funds for poor families.

Mi negra: una oportunidad para salir de abajo

Yellow Lula

Rosales’ approval of the redistributive rentist state would continue with the opposition’s next candidate in 2012 and 2013: Henrique Capriles. A known admirer of Lula Da Silva, Capriles sought to become a pink alternative to Chavismo: while offering the same vague proposals as Rosales, he also announced he would stop and review nationalizations and bring RCTV back—an opposition television channel closed by Chávez in 2007.

Nevertheless, Capriles also promised not to re-privatize the national telecommunications company CANTV (re-nationalized by Chávez in 2007) and based much of his campaign on the promise of keeping Chávez’s misiones by institutionalizing them through a Missions Law. In fact, Capriles—seeking to become a Venezuelan Lula—promised to maintain Chávez’s welfare programs by designing them to be direct cash transfers (like Lula’s Bolsa Familia) and adding them to the country’s ordinary budget. He also proposed educational programs, job credits and aid for the elderly. At the moment, conserving the Bolivarian state that had sustained Chávez’s high popularity levels was the only way to compete with Chavismo.

If Chávez had been defeated in 2006 or 2012, Venezuela perhaps would still have remained in the path of the pink tide: albeit the Lula way—a market economy with a strong welfare state and public-private partnerships. Similarly, while candidates stressed redemocratization and depolarization, their bland approach to the red PDVSA, public institutions and the 1999 Constitution didn’t promise a renunciation of the “Fifth Republic.”

The Unity Objectives

On January 23, 2008 a group of ten parties signed the “National Unity Agreement” that created the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD). The Agreement included ten consensus objectives that have become a common framework for the general opposition ever since. Including: independent republican institutions and respect for the 1999 Constitution, civil and political liberties, regional and municipal decentralization, security from crime, the protection of private property and economic liberties (and a well-managed PDVSA), poverty reduction (and it explicitly mentions depoliticizing the misiones and making them effective), non-ideologized quality education, a foreign policy based on solidarity with other countries from the region and the world, non-politicized and institutionalized Armed Forces and oppositional unity to achieve the ousting of Chavismo.

Seven years later, the coalition—now including more ideologically diverse parties—won the National Assembly with a supermajority. The opposition now seemed fated to take the reins of the country.

2016: The Country That Never Came

“We commit (…) to the activation of Constitutional mechanisms to achieve political change” in the first semester of 2016, Lilian Tintori says in an animated video for the 2015 parliamentary elections campaign. In the video, the MUD promised to achieve “the best Venezuela”—represented as a building surrounded by palm trees and rainbows in a mountain rising besides some ruins named “dictatorship”—either through a recall referendum, Maduro’s resignation, a Constitutional amendment or a Constituent Assembly.

The Venezuelan opposition’s victory in the 2015 parliamentary elections was the closest that it had ever been to power since the Carmonazo. While it continued professing the Unity objectives, the opposition started proposing and approving a series of laws and reforms that gave us a glimpse of what an opposition-run country would have been.

The opposition approved a reform granting more autonomy to the Central Bank of Venezuela and another one trying to limit Maduro’s plans for the Orinoco Mining Arc, abolished political bannings (inhabilitaciones) while politicians are still being prosecuted and reestablished the Caracas Metropolitan District eliminated by Maduro. The Assembly also approved laws ordering “culture of peace” courses in every educational institution, limiting enforced presidential broadcasts (cadenas), granting property rights to Misión Vivienda beneficiaries and even proposed a wage law that would define salaries in dollars. It also rejected Maduro’s Economic Emergency Decree and wrote an economic report promoting the protection of private property, the elimination of currency exchange controls and certain moves towards economic liberalization. Hell, some Mérida congressmen even spoke about returning RCTV to the air.

Many of these proposals signified a return of technocratic governance and the professional classes in public policy, for example by allowing the Assembly to name Central Bank authorities or letting it have a say on concessions to exploit natural gas. Nevertheless, none of these reforms, laws and proposals came to be. Since day one, the Chavista-controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) overturned every law passed by the Assembly. In 2017 it even granted itself the Assembly’s powers, a decision that led to deadly protests for months. By 2019, the TSJ had approved 104 rulings (41 in 2016 alone) limiting or annulling the Assembly’s functions as well as annulling 16 laws. The 2015 Assembly, after years of harassment and persecution, ended up extending its own term limits when the 2020 elections were widely denounced as fraudulent. It now “legislates” over Zoom.

The six months to oust Chavismo became seven years and counting.

Venezuela’s Failed Marshall Plan

The confrontations between the Maduro regime and the National Assembly peaked in January 2019, when the Assembly proclaimed its president—Voluntad Popular’s Juan Guaidó—as interim president of Venezuela after denouncing the 2018 presidential elections as a sham. With the support of more than 60 countries, and seemingly fated to take Miraflores Palace, Guaidó went on to present his “Marshall Plan:” Plan País.

Despite Voluntad Popular’s membership in Socialist International, Guaidó’s plan represented a break with the opposition’s previous redistributive proposals. The opposition’s most complete plan to date, Plan País was a fairly neoliberal vision for Venezuela. The plan proposed privatizing public services (with the state as regulator), allowing foreign investment in the oil industry and foreign companies having a majority of shares in mixed projects with PDVSA, applying for funds from multilateral bodies, eliminating currency exchange and price controls, demilitarizing and decentralizing security forces, remaking the judicial system, federalizing Venezuela, eliminating indefinite presidential reelection and reducing the state. This proposal is bolder than Carlos Andrés Pérez’s Gran Viraje or Rafael Caldera’s Agenda Venezuela and its “apertura económica.”

Surprisingly, the proposal received criticism from the most libertarian opposition pundits. They criticized Plan País for proposing a nutrition program for children and pregnant women as well as handing out temporary direct subsidies and preferential prices for the most vulnerable segments of the population—only while the humanitarian emergency and its immediate consequences lasted.

More importantly, Guaidó’s Plan País represented a rebuttal to Chavismo’s discourse. “For chavismo, privilege always comes cloaked in a powerpoint presentation,” wrote Quico Toro in 2007, “Dismissing all deliberation and all specialist discourse as a way of managing society, chavismo is left to rely on the will of the leader alone.” For example, Chávez fired the National Library’s head of historic cartography and the head of its rare books division because both signed a recall referendum against his rule in 2004. Both were replaced with loyalists with no specialist training for these highly specialized jobs.

Meanwhile, Guaidó’s Plan País was developed by some of Venezuela’s brightest minds like Harvard’s Ricardo Haussman and UCAB’s Luis Pedro España. Guaidó even received proposals from Caracas’ five most respected universities.

But three years later, after years of drifting senselessly away from Miraflores, Guaidó was ousted by congressmen from the 2015 National Assembly. The Plan País website is now offline.

Towards 2024

So, now what?

It’s still early for opposition candidates to present their proposals. Most of the possible pre-candidates are simply repeating the generally liberal Unity objectives and remarking, as usual, that they are not Maduro.

It’s possible that Juan Guaidó, if he actually ends up running in the primaries, will keep his Plan País. Carlos Ocariz, who could become Primero Justicia’s candidate for the primaries, has also talked about “direct democracy” (albeit, describing using oil revenues for direct cash transfers). César Pérez Vivas has proposed a market economy, the elimination of presidential reelection, a bicameral Congress and a new “apertura petrolera.” The comedian Er Conde del Guácharo (Benjamín Rausseo), who could end up running as an outsider and admires the Austrian School, repeats the mantra “a country of owners” and María Corina Machado has her own proposal from 2018: Tierra de Gracia.

It’s a sort of Gran Viraje redux: a vaguely neoliberal vision of “a liberal republic” with a decentralized state that promotes private enterprise, is integrated to global markets and generates wealth not through oil rentism but through capitalist production. More recently, as she starts the engines for her presidential campaign, Machado has been clearer in her proposals than most candidates: she advocates for “a massive, accelerated and absolutely transparent process” of “privatizing everything, including the oil industry”—a bold move in super-statist Venezuela. She’s also proposing a remake “from the base” of the Judicial Power, a return to parliamentary bicameralism, subduing the military to civilian authorities, eliminating presidential reelection, releasing all political prisoners and the end of state-enforced censorship. “Start criticizing the presidenta!” she said.

Be it Rausseo’s country of proprietors, Guaidó’s Plan País, Pérez Vivas’ “10 proposals” or Machado’s Tierra de Gracia, it seems the age of oppositionist Lulismo ended with the massive crisis the country experienced in the mid and late 2010s. Capriles and the opposition’s Brazilian model was a product of the Chávez oil boom—and it died with it, despite the insistence of many. The opposition, now facing a bankrupt country with a non-competitive economy, has seemingly done a neoliberal turn.

And it goes beyond economics: Julio Borges, who claimed in 2009 that Chavismo wasn’t socialism but state capitalism, now blames the São Paulo Forum for the Black Lives Matter protests. Delsa Solórzano, who used to describe herself as a democratic socialist back in 2011, now leads a party that self-defines as “center right.” Leopoldo López, who created a party that joined Socialist International in 2014, recently endorsed Keiko Fujimori and José Antonio Kast. Machado, alongside Eric Zemmour and Marjorie Taylor Greene, was even invited to be a speaker at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Mexico this year (despite a Peruvian speaker’s rebuttal).

Still, candidates need to answer more questions. We know they want political prisoners free, we know they want independent institutions and we know they are not Maduro. But Venezuela has experienced a colossal collapse with few historical precedents in the region. Such a panorama—economically and socially similar to a post-war country—demands bigger answers: If the opposition wins, would Venezuela return to bicameralism? How are we ensuring new judges in the judicial system? What would PDVSA’s role be in a reconstructed oil industry? What will happen with the Orinoco Mining Arc? Are expropriated properties going to be returned to their original owners? Would they privatize CANTV, Corpoelec and Hidrocapital? Is there a plan to attract professionals from the diaspora and tackle Venezuela’s labor deficits? Are we getting a new Constitution? Even symbols are at play. Are we eliminating the word “Bolivarian” from the country’s name? Are we keeping the flag’s eighth star? Will we have a Museum of Memory?

The opposition, demoralized and disappearing into oblivion, needs to make people believe in an alternative if it wants to win. It needs to show a vision of a country that is radically different from the Madurista model—which is now appropriating some of the opposition’s liberalization proposals. Polarization and over-politicization are fading. Anti-politics is on the rise again and the performance of the primary candidates in polls is dismal. To win the hearts of voters in 2024 being anti-Chavista will no longer be enough.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate