Maduro’s Evil Plan to Fragment the Opposition

Maduro’s government divides the opposition by granting legitimacy to anti-PUEDE movements through meager concessions

“The signing of the second partial agreement between the Bolivarian Government that I preside over and the Unitary Platform of one of the oppositions opens a new chapter for Venezuela,” tweeted Maduro soon after the Social Protection Agreement was signed in Mexico by the delegations of Chavismo and the Unitary Platform. A few days later, Maduro described the Unitary Platform as “a group of putschist political parties” that represents “one sector of the opposition that has 28% of the vote and we reached out to them to bring them to the way of democracy.” In his narrative, clearly based on the results of the 2021 municipal and regional elections (when most voters voted for disunited non-Chavista coalitions), the Unitary Platform—which amasses the mainstream opposition parties—is just a minority of extremist pro-American parties within a large sea of ‘oppositions.’

Chavismo’s “oppositions” narrative has been gaining steam since the 2021 regional elections. In fact, just one day after the elections, Jorge Rodríguez—who leads the Chavista delegation in Mexico and the disputed 2020 National Assembly—said that “a new oppositional option that is different from MUD’s extremism is appearing” and asked for Alianza del Lápiz, Fuerza Vecinal and the Alianza Democrática coalition to be included in the Mexico dialogue. The strategy is clear: drown the Unitary Platform with loyal opposition groups and it will be one insignificant voice in a lousy chorus.

In fact, a recent study of electoral patterns by political scientists Maryhen Jiménez, Stefania Vitale, Juan Manuel Trak and Guillermo Tell Aveledo shows why Chavismo is so insistent in highlighting the ‘diversity’ of the oppositions. “As A result of its electoral-authoritarian engineering, it [Chavismo] has managed to impose itself as the primary political force despite its continuous decrease of popular support,” the study says, “the data and indicators presented in this article show us that, effectively, when the opposition has coordinated its actions, even in a context of authoritarian consolidation” it has managed improvements in competition or electoral victories while “when it has been divided in the elections, it has fragmented the vote and facilitated the victories of Chavismo.”

Boosting and promoting multiple loyal oppositions, to the detriment of the Unitary Platform, is Chavismo’s secret weapon for the 2024 presidential elections and its struggle for legitimacy, all in the context of the talks in Mexico and the opportunity they pose to free Maduro of the international sanctions that limit him so.

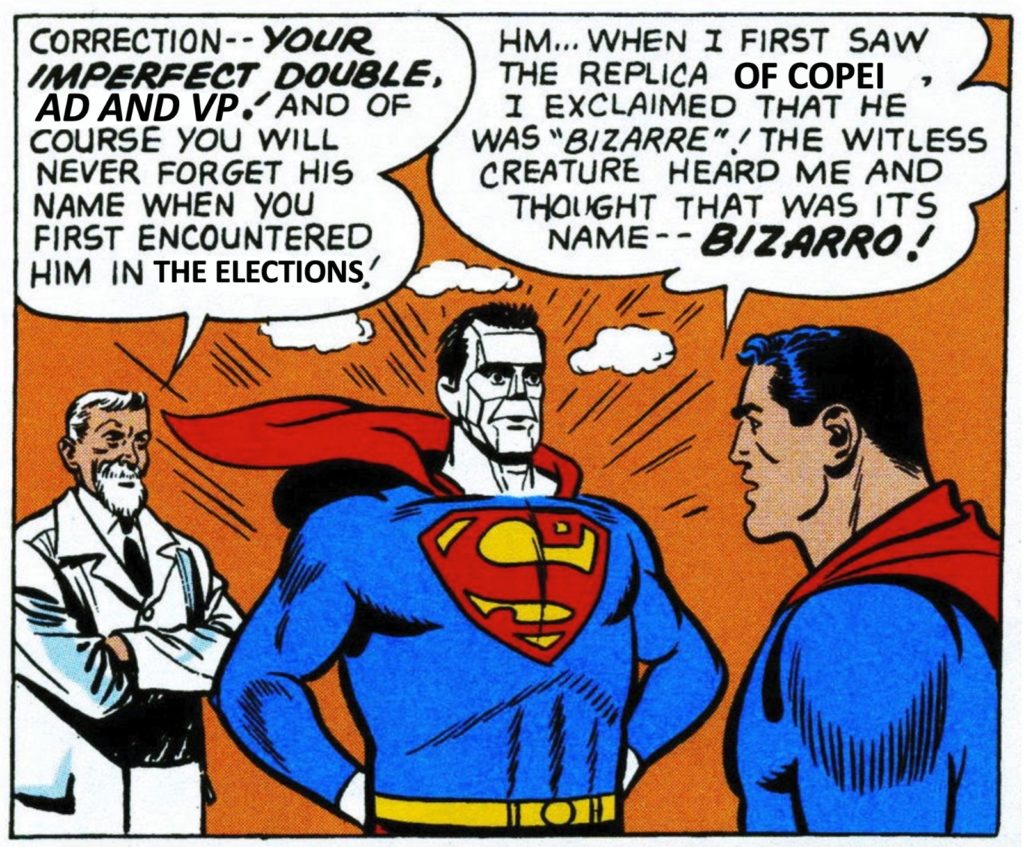

Alianza Democrática’s Bizarro World

Maduro’s attempt to divide voters and create a mirage of democracy relies on the existence of opposition factions that are legitimate or popular enough to pull voters away from the Unitary Platform, but not the leverage to actually pose a threat to Maduro (the Platform has the backing of the United States and influences its sanctions policies). This is where Alianza Democrática, Alianza del Lápiz and Fuerza Vecinal play key roles.

Alianza Democrática is usually seen as a coalition of former opposition congressmen (like Luis Parra and José Brito) accused by the National Assembly of helping Maduro’s crony Alex Saab, the small “loyal opposition” parties of la mesita—Maduro’s first attempt to create a potemkin negotiation table with nominally opposition but friendly parties—and puppet parties created through interventions of opposition parties by the Chavista-controlled Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ): exact dopplegangers of Acción Democrática, Copei, Voluntad Popular and others.

The coalition began during the 2020 parliamentary elections, denounced as fraudulent by much of the opposition (including Alianza del Lápiz) and its international allies. Despite that, Alianza Democrática ran in these elections, seeking to replace the opposition-controlled 2015 National Assembly, after Brito and Parra’s attempt to take it over from Guaidó earlier that year failed.

Thus, the mainstream opposition sometimes describe the coalition as a group of “alacranes” (scorpions), a pejorative term for opposition politicians seen as loyal to Chavismo.

Nevertheless, during the 2021 regional elections, the coalition included other groups like Movimiento Ecológico and Avanzada Progresista. The latter was intervened afterwards by the National Electoral Council (CNE), leading to the ousting of its leader Henri Falcón who then created Futuro: a new pro-Unitary Platform party. In fact, some of these parties actually supported the Platform’s candidate in Barinas—against Alianza’s parallel candidate—when the TSJ ordered a repetition of the elections after the opposition won the governorship.

Since then, the coalition has been thinning out. In its recent communiques, bashing the Unitary Platform’s primaries, it seems to now be composed of AD’s and Copei’s doppelganger, the intervened Alianza Progresista and the parties of Javier Bertucci and Timoteo Zambrano. Brito, who leads a copy of Primero Justicia called Primero Venezuela, met with the Commission of Primaries but said he would only participate if his personal sanctions are lifted.

Such communiques and criticism of the primaries show the real purpose of this group: to fraction the opposition vote and launch parallel candidates to those of the Unitary Platform, be it the repetition of the Barinas elections or the upcoming presidential elections. While the group won almost 15% of the vote in the last elections, it won most of its municipalities with candidates representing the intervened AD and Copei: winning rural voters, through the use of the parties’ cards in the electoral ballot, who remain loyal to the two parties that ruled Venezuela before the Bolivarian Revolution but are unaware that the non-intervened versions of the parties are under the Unitary Platform’s card.

On December 2nd, Maduro had the first of his parallel “peace dialogues” with members of Alianza Democrática: specifically the aforementioned parties from the recent communiques and Primero Venezuela. Besides talks of electoral reform and “unifying views that contribute to the social and economic growth of the country”, not much came out of the meeting. But this was never its intention.

By meeting with the group, and even promising a possible electoral reform that could bring members of Alianza Democrática into the CNE board (diminishing the leverage of opposition-leaning members like Roberto Picón), Maduro is once again propping up the group’s role of hijacking and dividing the opposition but also to play along as “the opposition” in the regime’s democratic theater: for example, Alianza Democrática will be there to supposedly run against Chavismo if unabashedly unfavorable electoral conditions lead to the Unitary Platform walking away from the 2024 presidential elections.

Playing Democracy with Alianza del Lápiz and Fuerza Vecinal

Alianza del Lápiz, a party supposedly based on the thought of Arturo Uslar Pietri and led by Antonio Ecarri, saw a chance to place themselves in the spotlight when Maduro came calling for a public meeting. That meeting took place in Miraflores Palace on December 7th and concluded with Ecarri—who ran for mayor of Caracas in 2021 against both Chavista and Unitary Platform candidates—announcing that he and Maduro had reached several agreements among which was the relaunching of an improved school food program, a call for the CNE to set a date for the 2024 elections and a public rejection of international sanctions.

None of these agreements actually hurt Maduro or his regime, the last one even plays in his favor and against the Unitary Platform, which is why Maduro gladly agreed to these requests as they only throw Lápiz the meekest of bones. In fact, Ecarri has no actual leverage to push for these agreements: they are rather potemkin concessions made by Maduro; facades that make his government look as if it’s pushing for democratization and political peace.

Ecarri plays along because he sees a chance to further his own campaign, one which is based on accusing both Maduro and the Unitary Platform of Venezuela’s collapse. Ecarri is so committed to the role that he even refuses to participate in the Platform’s primary, instead running his own presidential campaign. This serves Maduro’s goals which is why he is seeking to position Lápiz as an important opposition faction. We can expect similar scraps of legitimacy to be thrown their way in the coming months.

The final faction Maduro decided to play with in December is Fuerza Vecinal, a political party which currently governs the state of Nueva Esparta and thirty municipalities, including the opposition’s stronghold in east Caracas, and that styles itself as independent from the Unitary Platform. That independence has given FV a lot of space to work with, allowing them to benefit from the Platform’s reach (like when they ran joint candidacies in 2021) while also positioning themselves as a possible future alternative.

FV was invited by Maduro to a December 16th meeting in Miraflores which was attended by party leaders like David Uzcátegui, Gustavo Duque, and Manuel Ferreira, and which ended with Uzcátegui leading a press conference where he announced the requests they had made to Maduro. While some were mere political platitudes, Fuerza Vecinal requested the release of political prisoners and that the government facilitate displaced Venezuelan’s right to vote in the 2024 election from abroad while also stressing the importance of the Mexico talks. These actions would actually hurt Maduro if he were to grant them, which is why he didn’t nor should we expect him to, at least not in any way which would pose a threat to his 2024 victory. Fuerza Vecinal knows Maduro won’t grant them these requests, but they play along because it consolidates their image as an entity independent from the Unitary Platform and helps to position them as an alternative in the future. FV has mentioned its interest in participating in the Platform’s primary, going along with that plan and accepting the results would not be to Maduro’s liking which is why he’ll seek ways to pit them against each other.

In the end, Maduro doesn’t see either Lápiz or Fuerza Vecinal as actual rivals, but mere pawns in his strategy game to use against his actual foe.

All Oppositions Are Welcome (Except María Corina)

Of course, not all oppositions are useful to Maduro. While center-right politician María Corina Machado has a much higher polling rate than any candidate from the non-Platform groups, and sometimes even more than Unity pre-candidates, Maduro hasn’t sought to create a parallel negotiation table with her party Vente. Besides Machado’s expected refusal (she described negotiations in Mexico with the Unitary Platform as “a blackmail table” and the Social Protection Agreement as “vultures taking care of meat”), her position would be too anti-Chavista and confrontative to actually be useful for Chavismo. Machado’s proposal is truly counterrevolutionary.

In fact, unlike his amicable invitations to other non-Platform groups, Maduro recently attacked Machado on television after she proposed privatizing state assets.

“Machado launched today her campaign and her main promise is to privatize everything (…) the people will avoid the return to power of the surnames and the oligarchy in Venezuela”, he said, “You’ll see the big fat surnames of the Machados, you’ll see them in the streets and in battle.”

Machado’s recent meetings with the Commission of Primaries and with Carlos Ocariz—who could end up being Primero Justicia’s pre-candidate—seems to show closer relations with the Unitary Platform and its primaries. Nevertheless, her influence could be useful to Maduro if she decides not to run: continuing her stance as a pro-abstention voice, critical of the Platform and its leaders, especially in the opposition’s middle-class core. But this won’t depend on Maduro’s approach or a parallel negotiation table but rather on Machado’s own strategy and decisions as the primaries approach. Maduro needs to focus only on amicable groups.

In fact, it’s hard not to notice the order in which Maduro invited the chosen factions over to Miraflores: Alianza Democrática first, Lápiz second, and Fuerza Vecinal third. That’s probably not a coincidence. It seems Maduro has ordered their appearances according to the level of threat they pose to him in the 2024 elections. He knows quite well that Alianza Democrática won’t pose a challenge, he knows Ecarri doesn’t really expect to be president in 2024 and is only building his brand, and he knows that Fuerza Vecinal is better off biding its time by the Unitary Platform’s side for the time being and are unable to do anything that threatens their control of the rich municipalities.

As we draw closer to the Platform’s primary, and 2024 in general, we’re likely to see more of these meetings in parallel to the Mexico talks. We might even see new “concessions” being made by Maduro to his chosen factions in an attempt to lend some legitimacy to their campaigns and we may even begin to hear about new “oppositions” going forward. One thing’s for sure: the rhetoric’s not going anywhere.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate