Peru: A Troubled Government Scapegoats Venezuelan Migrants

Ignoring the commitments made in the last Summit of the Americas, the Castillo administration expanded the reasons for deporting Venezuelans. Which are the implications for Latin America?

Photo: Ernesto Benavides/AFP/Getty

On August 10th, amid a political crisis for President Pedro Castillo, the Peruvian Executive Office and Congress approved a co-sponsored bill that permits the deportation of undocumented migrants and migrants who have not completed the full COVID-19 vaccination schedule. The majority of those affected by these new laws are Venezuelans, who are close to one million and make the largest share of undocumented migrants in Peru.

This new law comes in the wake of the third impeachment attempt Castillo faces, who is also the subject of six criminal investigations, in a context of increasingly low approval rates for both the President and Congress. This restrictive legislation was passed only two months after the signing of the Los Angeles Declaration, where 20 governments in the region, including Peru, agreed to host more migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers and expand legal pathways to integration.

In our research and analysis of social media data in Latin America, we contextualize this reversal in light of regional trends by documenting how in multiple instances of political turmoil, migrants are used as scapegoats by political leaders and host citizens. The strategic use of migrants as policy bargaining chips for both global and domestic publics has implications for ambitious inclusion policies in the region that will likely span multiple electoral cycles and other moments of political volatility.

Venezuelan Migration in Peru

Peru is the second largest destination country for Venezuelan migrants, after Colombia. For the most part, Latin American governments had responded to the phenomena of Venezuelan mass migration with integration-oriented migration policies in spite of increasing anti-immigrant sentiment among their citizens. These measures for Venezuelans include free mobility across borders and access to emergency healthcare regardless of documentation, as well as special temporary protected statuses or asylum designations that confer additional rights to employment and education.

In Peru, however, the record for migrant inclusion is mixed. In 2021, the government reinstated a one-year special stay permit for Venezuelans after suspending the program for three years. Peru has also witnessed anti-Venezuelan discourse by politicians during elections and the prior passage of restrictive migration policies. For instance, in 2020, the Minister of the Interior called for a new police force specifically dedicated to crimes committed by migrants. The new law passed this week, the “1350 Migration Law” significantly expands the criteria for deportation, allowing for the expulsion of all irregular and unvaccinated migrants.

While in Europe and North America this is not uncommon, as undocumented migration is grounds itself for deportation, in Latin America such a policy constitutes a break from a regional accord of tolerance and regularization for irregular migrants from Venezuela.

Migrants as Political Tools

In our joint research with the Xenophobia Barometer, we show that anti-immigration policies and political speech have significant consequences on public support for integration. As part of our work, we collected and analyzed tweets from 2019 to 2022 that mention words related to migration in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. We then used text analysis to classify these tweets based on whether the message it contains discusses migration with a positive or negative connotation. We find that there are large spikes in anti-migrant messages that call for deportations, use slurs, and promote misinformation during moments of political instability or unrest, and that these are particularly responsive to political leaders’ speeches and statements.

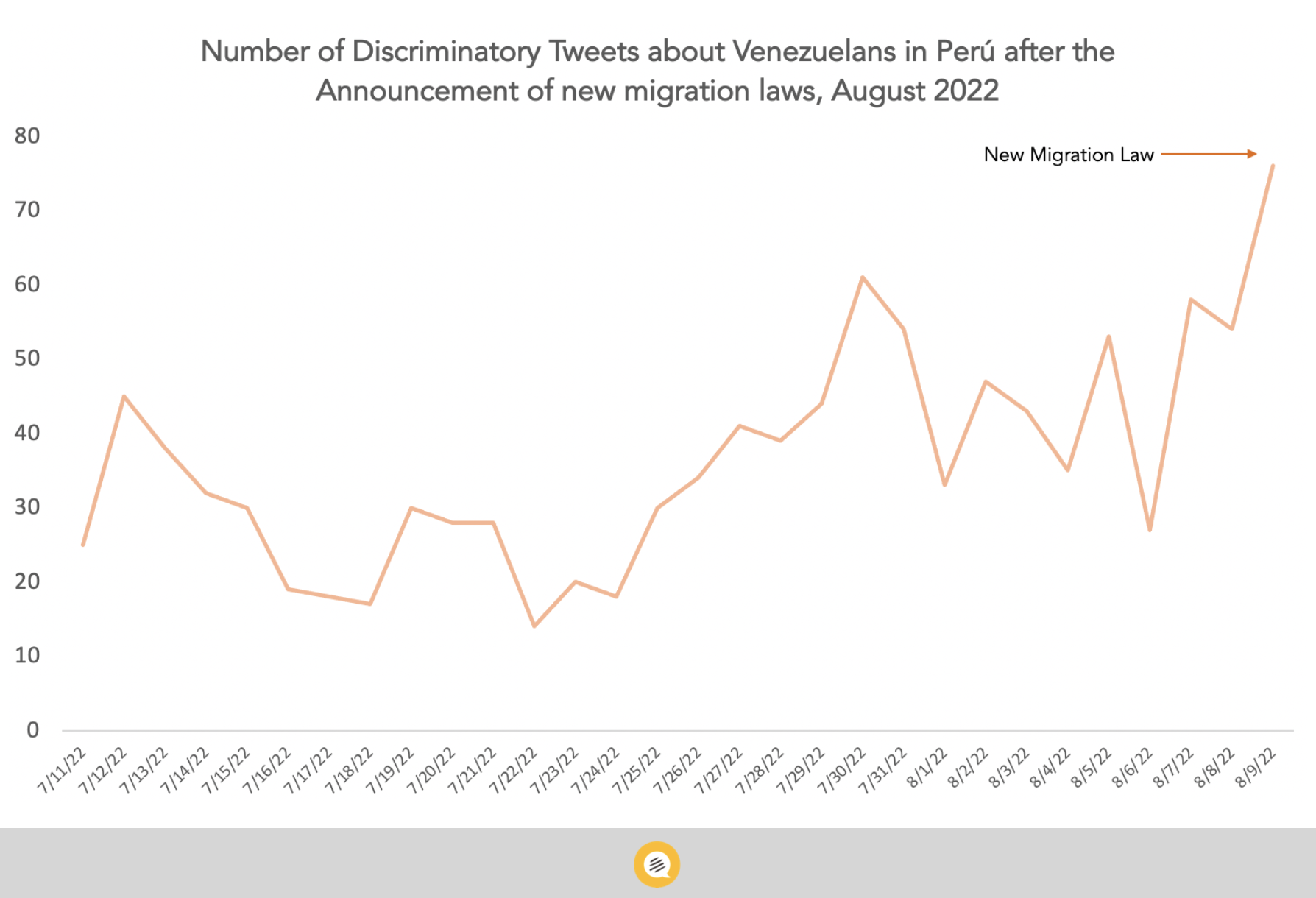

After the new migration law was sanctioned, Peru experienced an ongoing spike of messages with discriminatory content toward Venezuelan migrants on social media. A large part of these messages demands their expulsion. In the graph below, we show that the number of daily anti-Venezuelan posts were increasing by around a third in Peru when the new law was announced.

The days before the law was announced, the population knew about a crime where a Venezuelan citizen was involved, and a TikTok where another Venezuelan was criticizing Peruvian cuisine went viral. Such events help explain why the public speech about expelling Venezuelans was getting louder. We still don’t know whether the new law impacted the subject on Twitter.

This is not the first time this year that Venezuelan migrants have been used to distract from political crises in the region. In April, there was a national truck driver strike in Peru, during which rumors spread on social media accusing migrants of being paid to participate in the protests and of being agents of a communist agenda aimed at destabilizing Latin America. In Ecuador, during the anti-government protests of June 2022, rumors spread on social media saying that Venezuelans are paid agents to incite violence and looting leading to an uptick in anti-immigrant sentiment. While no actions were taken against migrants in these instances, similar accusations made on social media in 2019 led to the discretionary deportations of 59 Venezuelans from Colombia without trial.

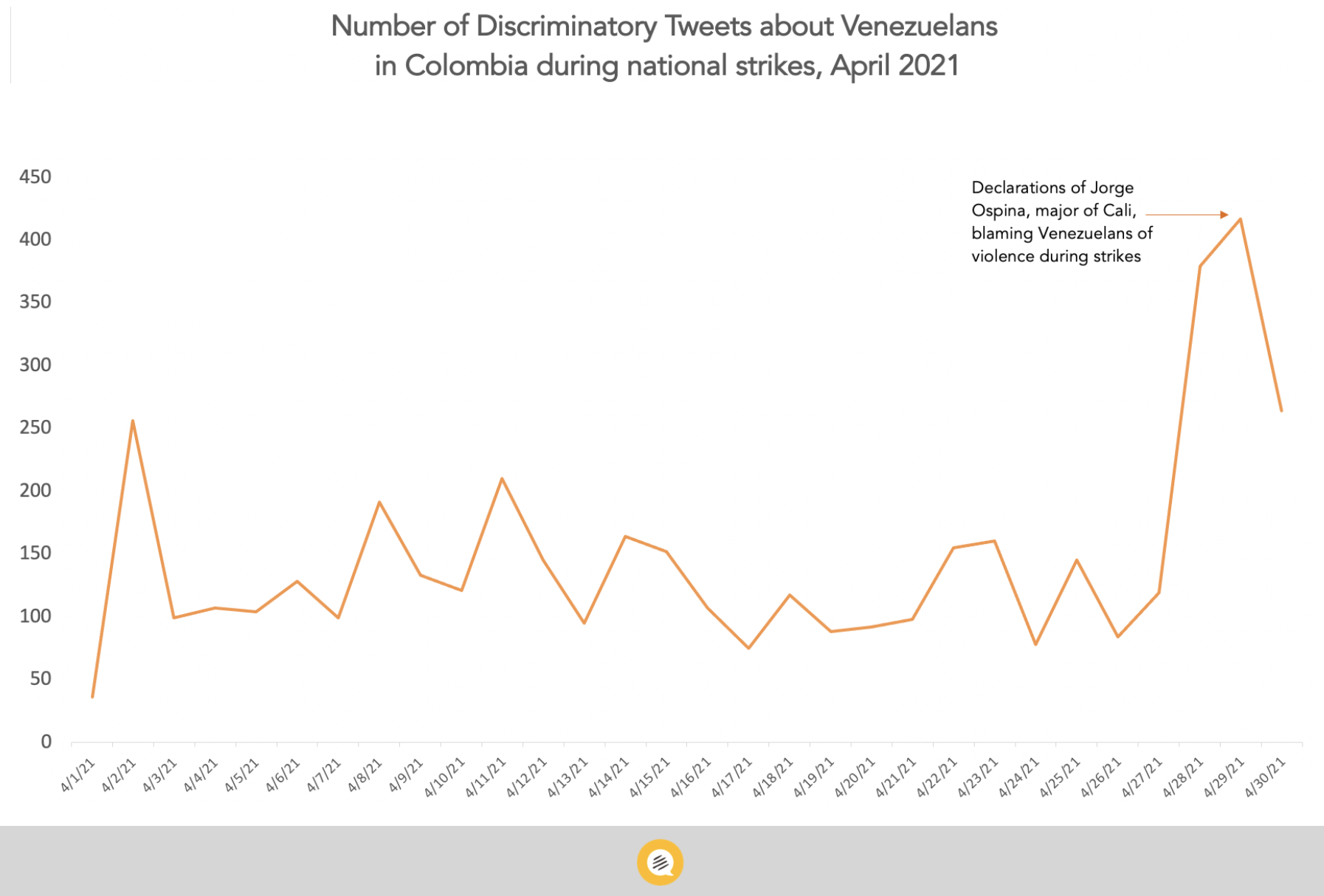

We also find that these peaks of anti-immigrant messages are particularly responsive to cues from political elites. Our graph below shows an increase in discriminatory tweets after the mayor of a regional capital, Cali, blamed Venezuelans for the unrest during national protests against the Colombian government in 2021 and called for their deportation. In fact, a similar pattern took place with the Bogota mayor, Claudia López, and the Constitutional Court quoted our data to ask the mayor to take back her statement.

What’s troubling about these patterns is that the political crises are largely unrelated to matters concerning migration. President Castillo of Peru is facing an institutional crisis and a lack of support from Peruvian citizens, while the protest movements in the three countries were led by citizens and ignited by grievances against their own governments. Blaming Venezuelan migrants provides an easy out for political leaders in times of difficulty.

The scapegoating of migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers during unrest or insecurity is not unique to Latin America. Scholars find that governments take action against migrants because swift action creates the appearance of authority, and that foreigners are expedient targets because they are nonvoters and often lack rights, or the ability to protect their rights. In the U.S., for example, responses to the 9/11 attacks and the pandemic have led to stronger prejudice against immigrants and acts of violence against minorities. Other governments in Eurasia have directly used migrants as political weapons and bargaining chips.

Broader Implications for Migration in Latin America

What Peru’s new law reveals is that the commitment to hosting and integrating migrants in Latin America, the majority of whom are Venezuelans, cannot be taken for granted. Changes in incentives for these governments—whether that be from new constituency bases, emergent security situations, or crises of legitimacy—can alter their political calculations. Long-term political will for migrant integration depends on the continued alignment of pro-migration policies with the strategic political and financial incentives of Latin American governments. This alignment is harder to maintain in the context of political instability and volatility, as has been the case in Peru over the past years.

With the recent events of Peru, the regional protest movements this past year, the new wave of leftist leaders who took office within the last year in Latin America—many of whom promise reforms and claim to represent the politically excluded over the elite—it remains to be seen whether the momentum gained by integrationist agendas will be sustained.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate