The Iconic Painting by Arturo Michelena We Lost (and Recovered) in the U.S.

Many of us admired the copy of ‘The Sick Child’ at the National Art Gallery of Venezuela. Axel Stein managed to reconstruct the complete history of this work, in Venezuelan hands in the U.S.

This is the original Sick Child by Arturo Michelena

Axel Stein, a curator and Venezuelan art consultant who headed Sotheby’s Department of Latin American Art, didn’t expect that a curious fact from the catalog of the exhibition Genius and glory of Arturo Michelena, 1863-1898 on the Centenary of his death (Gallery of National Art in 1998) would take him on a journey.

Reading the text by Venezuelan researchers Rafael Romero and Juan Ignacio Parra Schlageter, who were in charge of the exhibition, Stein discovered that The Sick Child (1886), by the painter Arturo Michelena, exhibited for many years at the Galería de Arte Nacional in Caracas, was a copy made by the same artist. The original piece had disappeared a century ago.

This is the copy that is in Venezuela, much darker than the original

The original was painted during Michelena’s time in Paris. At only 22 years old, the painter born in Valencia, Venezuela won a scholarship created by the government of Joaquín Crespo in 1883 to commemorate the centenary of the birth of Simón Bolívar. This opportunity allowed him to study fine arts in Paris. Two years later, on March 6, 1885, he embarked on the ship Ville de Paris with renowned painter Martín Tovar y Tovar, who had just finished the famous battle scenes at the Elliptical Hall of the Legislative Palace and was returning to Paris, where he became the protégé of Venezuelans Bernardo and Ana María Tarbes, and enrolled in the prestigious Academie Julian, where another genius of Venezuelan arts, Cristóbal Rojas, was already studying.

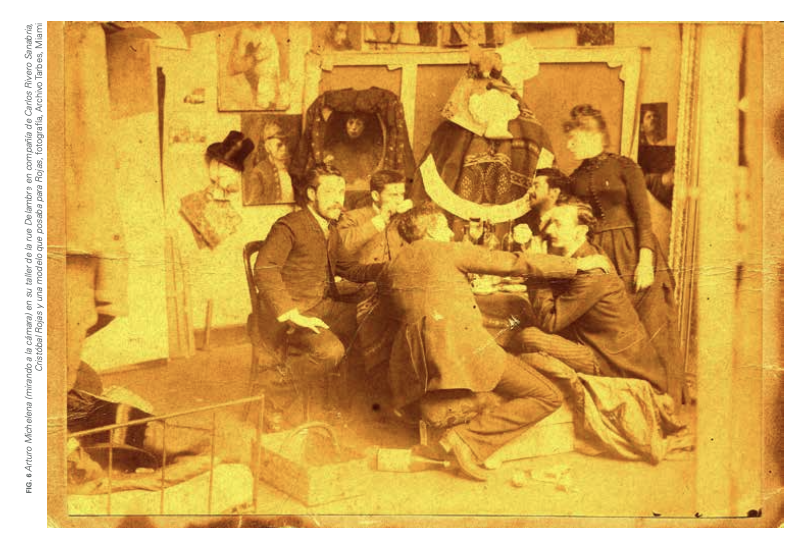

This photograph, owned by the Tarbes Archive, shows Michelena (left) in Paris with Rojas and other artists

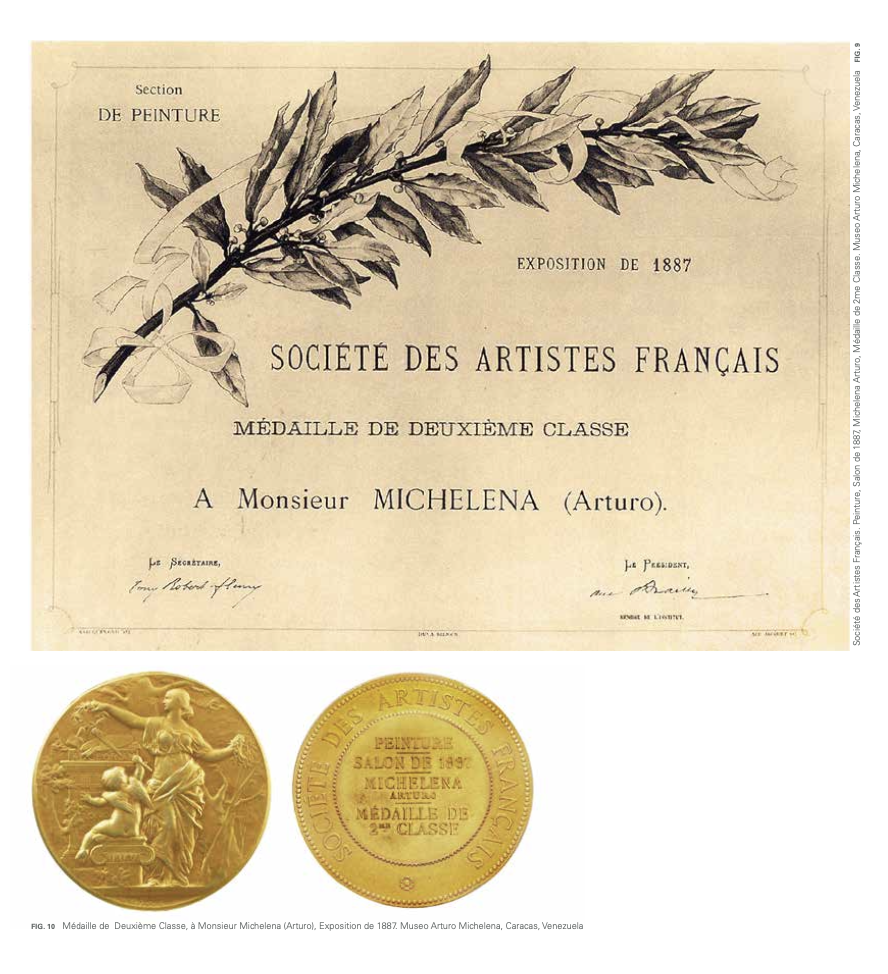

French portraitist Jean-Paul Laurens, who mentored Michelena’s work at the Academie, quickly discovered the young man’s talent. In 1887, Laurens proposed that Michelena should exhibit at the Salon of French Artists. Michelena sent the Enfant malade and La visite electorale (The electoral visit). The Salon awarded him the Médaille d’Or in second class.

Both paintings are from a period when “some Venezuelan artists had a good presence in Europe at the end of the 19th century,” says Stein. At that time, Cristóbal Rojas shared an apartment and studio with Arturo Michelena. Emilio Boggio Dupuy, a neo-impressionist from La Guaira who was friends with Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, also arrived in the city when he was very young and developed his artistic career there. Tovar y Tovar, “Guzmán Blanco’s favorite artist,” was also in town and “was well known,” says Stein. But Guzmán Blanco would revoke Michelena’s scholarship at some point, apparently because he wanted the artist to be in Rome and not Paris.

Two years after that Official Salon in which Michelena participated, the Universal Exposition in Paris was organized to celebrate the centenary of the French Revolution. At that event, where the industrial and scientific achievements of the “enlightened world” like the Galerie des Machines made of glass and iron, the Palace of Fine Arts with its glass and ceramic roof, and the newly opened Eiffel Tower were presented to amazed crowds, Michelena would exhibit his well-known Charlotte Corday On The Way to The Scaffold, along with The Sick Child and The Electoral Visit.

The diploma and the medal awarded to Michelena in Paris

At the Universal Exposition, Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor bought L’ Enfant Malade. She was a New York socialite of the Gilded Age, wife of William Backhouse Astor, a member of the prominent American business family. Thus, the work would end up hanging with a dozen academic paintings in the enormous room of the outlandish French Renaissance-style mansion that the Astors had built between 65th Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

A few years later, at just 35 years old, Michelena died of tuberculosis in Caracas. And this is what was known in Venezuela, thanks to art critic Juan Röhl’s investigations tracing The Sick Child from the Parisian studio where it was made to its arrival in New York through the defunct Vincent Astor Foundation.

Axel Stein would later discover more.

An Original Michelena in the U.S.

Caroline passed away in 1908 and her son, John Jacob Astor IV, died shortly after on the Titanic. Vincent Astor—eldest son of John Jacob—had to take over the family at 21 years old. As a consequence of the succession, The Sick Child was auctioned through the American Art Association (AAA): the most important auction house in New York at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

In 1938, gallerists Otto Bernet and Hiram Parke bought almost all the shares of the AAA before it disappeared. And then, in 1964, the English house Sotheby’s—the oldest auctioneer in the world—bought Parke-Bernet with the intention of entering the United States market.

Axel Stein followed the trail of the Astors more than a century later, to reconstruct the entire trajectory of Michelena’s painting. He first found an old photo of the Astors’ hall with The Sick Child hanging among dozens of academic works at the Museum of the City of New York. Stein assumed that the supporting documents for the Astor sale would be at the Sotheby’s archives. “Fortunately, nobody throws anything away in the United States,” says Stein. “Venezuelans throw everything away, which is terrible. Because what now seems to us to be unimportant, tomorrow can be very valuable for a researcher.”

To access documents from past auctions, Stein contacted Elizabeth Gorayeb, a researcher at Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art Department. A month or two later, he received a box containing the documents from the auction on June 21st, 1926. The catalog described Arturo Michelena as an Italian artist and titled The Sick Child as The Doctor. The surname Burns was written over the catalog next to a sale price: $400 (or a little over $6,200 today), one of the highest at the auction. Now Stein knew the painting had been sold and for how much, but not to whom. When he searched the internet for Mr. Burns, the search turned up “like 500,000 Burns,” he explains. Tracking down the surname, then, was not the way to go.

With the help of acquaintances in Sotheby’s Old Master Painting Department, Stein came up with the name of Owen Burns, a late 19th and early 20th-century builder who came to own much of the city of Sarasota, in Florida. Owen Burns, Stein found out, was a collector of antique art, a buying agent for John Ringling, the owner of a circus monopoly (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus) and also a collector of antique art. In fact, Ringling built the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota.

Stein called Burns’s descendants’ lawyer, who “had absolutely no idea of a painting purchased by Mr. Owen Burns.” The Venezuelan curator then thought that the story ended there: “If no one has any idea about this painting, where am I going to look for it?” he said to himself. But two or three weeks later, he received a call from Aaron de Groft, director of the museum in Sarasota: there was a painting, without a file or record, in their deposits. Burns’s descendants, very old then, remembered seeing The Sick Child in the Burns home until 1937, when it was given to the Sarasota Library for permanent display.

The library then loaned the painting to the local chapter of the National Society of the United States Daughters of 1812 and Stein suspected that the society had kept the painting in the vaults of the city museum, to comply with the order given to public collections to safeguard works of art in case of invasion or bombardment when the United States entered World War II in 1941.

Accompanied by Burns’s heirs, a century after the Universal Exposition, Stein went to the deposits of the Floridian museum to “recognize the Child.” And there, in early 2004, he finally found it with the words Médaille d’Or still written in chalk on the back, and in all its fantastic detail: the torn posters on the wall of a house as if about to collapse, the mark of a hand on the cold window.

One of the things that surprised him the most was that the original work is significantly larger than the GAN copy, which measures 80 x 85 cms. The one Stein found in Sarasota is 8 by 10 feet. After the discovery, the original was sent to the Simon Parkes workshops in New York for restoration, as the black bitumen in the painting had cracked and the varnish had darkened.

Stein thought that the Venezuelan State, given the unprecedented boom in oil prices, would be interested in purchasing the original painting. “The government was drunk on money,” he says. So Stein’s partner in Caracas, Diana Boccardo, contacted Farruco Sesto, the newly appointed Minister of Culture, to inform him of the finding. But, says Stein, “the minister’s response was: ‘there are too many old paintings in the National Art Gallery, no other is needed.’” Stein was astonished. Shortly after, Sesto would eliminate the autonomy of the museums as part of his process of “institutional refunding”.

The Sick Child was then auctioned off in November 2004 and purchased by a well-known Venezuelan business family for $1,450,000. “To this day, it’s the Venezuelan painting that has achieved the highest price at an auction,” says Stein. “More than Cruz-Diez, more than Soto, more than anyone.”

The Missing Sister Painting

The second piece with which Michelena participated in the 1889 Universal Exposition was yet to be found: The Electoral Visit, the canvas that accompanied The Sick Child. But its current appearance was not known, only an engraved copy considered lost and reproduced in a 1973 book by the art critic Juan Calzadilla was known in Venezuela.

A month after the auction of The Sick Child, Stein received an email from Didier Brunschwig, the president of a Swiss business group that included department store Le Lido, formerly known as Au Bon Marché, which was founded in 1872 by his great-great-grandfather, in Vevey, Switzerland.

Brunschwig, who had found out about the auction of The Sick Child, explained that the painting was hanging on the central staircase of the store in “immaculate” conditions. No one in the family remembered where it came from and they now suspected it had been bought in Paris from a previous owner.

This is how on May 24th, 2005, The Electoral Visit was auctioned in New York and bought by the same Venezuelan family that purchased The Sick Child. At this moment, the two paintings are together again, after being purchased by different people at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889.

This is “An Electoral Visit,” that reunites with its sister painting after the 1889 Expo

A couple of months ago, The Electoral Visit and The Sick Child were exhibited to the public for the first time together with works by Armando Reverón and Héctor Poleo in the exhibition Michelena. Reverón. Poleo. Seven Master Paintings, curated by Stein, at the Ascaso Gallery in Miami.

The original Sick Child hasn’t been to Venezuela yet. It went from Paris to New York, from there to Sarasota, and in 2004 it went back to New York, where it is now. “Neither of the two Michelena paintings at the Universal Exposition have been on Venezuelan soil,” says Stein. “The interest of the person who has it is to return it to the country. But not yet.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate