What Overturning Roe v. Wade Means for Latinas in the U.S.

If the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, this would add to an increasing list of difficulties for women, especially non-white immigrants

Last week, Politico published a leak from the US Supreme Court with massive consequences: an initial draft majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito that showed that they were going to strike down the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the legal resource that guarantees federal constitutional protection to abortion rights, establishing that abortions were constitutionally protected up until about 23 weeks when a fetus could be able to live outside the womb.

The name refers to a landmark lawsuit—Jane Roe was a pseudonym for Norma McCorvey, a 22-year-old unemployed woman who, pregnant with her third child, filed a case challenging Texas’s abortion prohibitions. She sued Henry Wade, who was the District Attorney of Dallas County. Roe vs Wade.

At that moment, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor 7-2. By the time the ruling was announced, McCorvey had given birth to a girl whom she placed for adoption.

What is happening now, simply put, is that a majority of Supreme Court justices (five of the nine), appear to be leaning to vote in favor of lifting the federal protection of abortion challenged by a Mississippi law that band abortion beyond 15 weeks of gestation. Alito, the author of the draft, quoted that Roe v. Wade was “egregiously wrong.” We know the draft is real: its authenticity was confirmed less than 12 hours after the leak was made public.

If Roe v. Wade is overturned, 26 states would pass laws that would ban abortions. 13 of them are states that have “trigger bans” in place, meaning that abortion will almost immediately be banned if Roe is no longer in effect.

The decision is still not final and we will likely not hear back from the Supreme Court until the end of June. But how would this change the situation for Latinas living in the US?

For starters, Latin Americans are one of the most uninsured groups in the country, especially those who do not speak English. According to census data, 1 in 4 Latinos don’t have health insurance coverage. And, even though Latinos make up 16.3% of the U.S. population, 25% of abortion patients in the U.S. are Latinas.

Strictly speaking about the 465,235 Venezuelans living in the US (like myself), 52.2% of them are women between 18 and 34 years (like myself). 236,882, or 50,92%, live in Florida. There, while abortion is not banned completely, the legislature did just pass one of the most restrictive abortion policies in the country.

Starting July 1st, women in Florida cannot legally receive an abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy (the previous one allowed them until week 24). They cannot count on telemedicine either—an alternative that is growing in popularity—because, under this new state law, the prescribing physician must meet with the patient in person at least 24 hours before the treatment. It does not make exceptions for cases of incest, rape, or human trafficking.

According to the Center for Reproductive Rights, if Roe vs Wade gets overturned or weakened, surrounding states like Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas would move to a total prohibition. That means that the closest option for a woman from Florida to have an abortion would be Illinois or Maryland—at least a two-hour flight. And that’s not an option for everybody.

Andreina Granados, a Venezuelan living in Tampa, mother of two, cannot imagine her life as it is now without abortion access. “Abortion saved my life,” she says. She became pregnant when her youngest was five months and while dealing with postpartum depression.

“They say this is an easy choice—it is not. It takes a toll on your mental health. But it was the best for me.”

She worries about a life with fewer rights, “especially after coming here from a country where they take so much from us.”

Latina women seeking abortions face cultural and language barriers, lower wages, little access to health insurance, shaky finance, and, in many cases, problems with their immigration status. In many cases, it also means doing everything alone, if your family doesn’t support the decision, something not entirely uncommon in the traditionally conservative Hispanic community (however, a Pew Research Center survey did found that in 2021, 58 percent of Hispanics in the U.S. believed abortion should be legal).

Gabriela Benazar Acosta, of the office of Communication and Media for Latinos from Planned Parenthood, explains more layers: people without a stable job face even more barriers because there’s no federal law ruling paid time off or sick days, “there’s nothing that guarantees a woman that they can take the time they need (to travel) without it affecting her negatively at work.”

“They’re not gonna end abortions, they’re just gonna put more and more barriers and pain to vulnerable people when they need compassion and support,” she adds. And 59% of the women who get an abortion in this country are already mothers. So, in order to get an out-of-state abortion, a woman needs to get time off work, transportation, and child care.

Whether we want to admit it or not, we are a vulnerable part of the U.S. population. Things can change from one day to the next. A Venezuelan living in Knoxville, Tennessee, sees this potential change as a culmination point on “a series of things that don’t help women at all.”

When asked to participate in this piece, she said she did not want her name to be published. It’s not hard to understand why: she’s right in the Bible Belt. Just this January the Planned Parenthood office in her city was burned down in a fire that the police established was arson.

In a country so vast and full of differences like the U.S., where you live plays an enormous role. In New York, where I live, Governor Kathy Hochul allocated $35 million to abortion providers in anticipation of increased demand if the US Supreme Court strikes down Roe v. Wade. For me and my friends, that’s a relief. “I don’t wanna be pregnant, I don’t wanna be a mom and I do everything in my power to avoid it. But knowing that in case of an emergency I can get one abortion gives me mental peace,” says Sofía Pereda, who adds that, because she lives here, she most likely will always have options. “I don’t wanna have an abortion, nobody wants to have one, but I like having the option of having one in case I need it.”

And what happens at the border?

We don’t know exactly how many Venezuelans are in Texas, and whatever that number is, it’s growing fast: just last December, U.S. Customs and Border Protection stopped 24,819 Venezuelans at the border. What we also know is that, of the 56,358 abortions performed in and out of state for Texans in 2020, 36% (20,348) were for Hispanics.

But that was 2020, which now seems like a distant reality. As of September 1, 2021, abortion is illegal in Texas once a fetal heartbeat can be detected—which can be as early as 6 weeks. It also financially incentivizes private citizens to let officials know if they know of someone getting an abortion. If someone successfully sues, they could receive a bounty of at least $10,000.

Many women from Texas were traveling to Oklahoma to get an abortion after this law was passed, so many that, in April 2022, the La Frontera Fund spent more than $13,000 on travel and accommodation fees. Before this law, they usually spent around $5,000 a year on that category. Oklahoma will fully prohibit abortion if Roe vs Wade is overturned.

Remember the long list of challenges women from Florida have to face? Well, in Texas, you have to add the fact that traveling for those who are undocumented is almost impossible. 100 miles into the state there are Border Patrol checkpoints. And if they cross the border to Mexico they risk not being able to go back to the U.S.

Talking to an activist on the border for this piece wasn’t easy. Big organizations are overwhelmed with requests, and smaller organizations or individual activists declined to speak out of fear of the fines. Although some of them use social media to share information.

Benazar puts it this way: the real consequences of abortion laws are not only women dying from doing an abortion with a hanger, it’s the criminalization of non-white women.

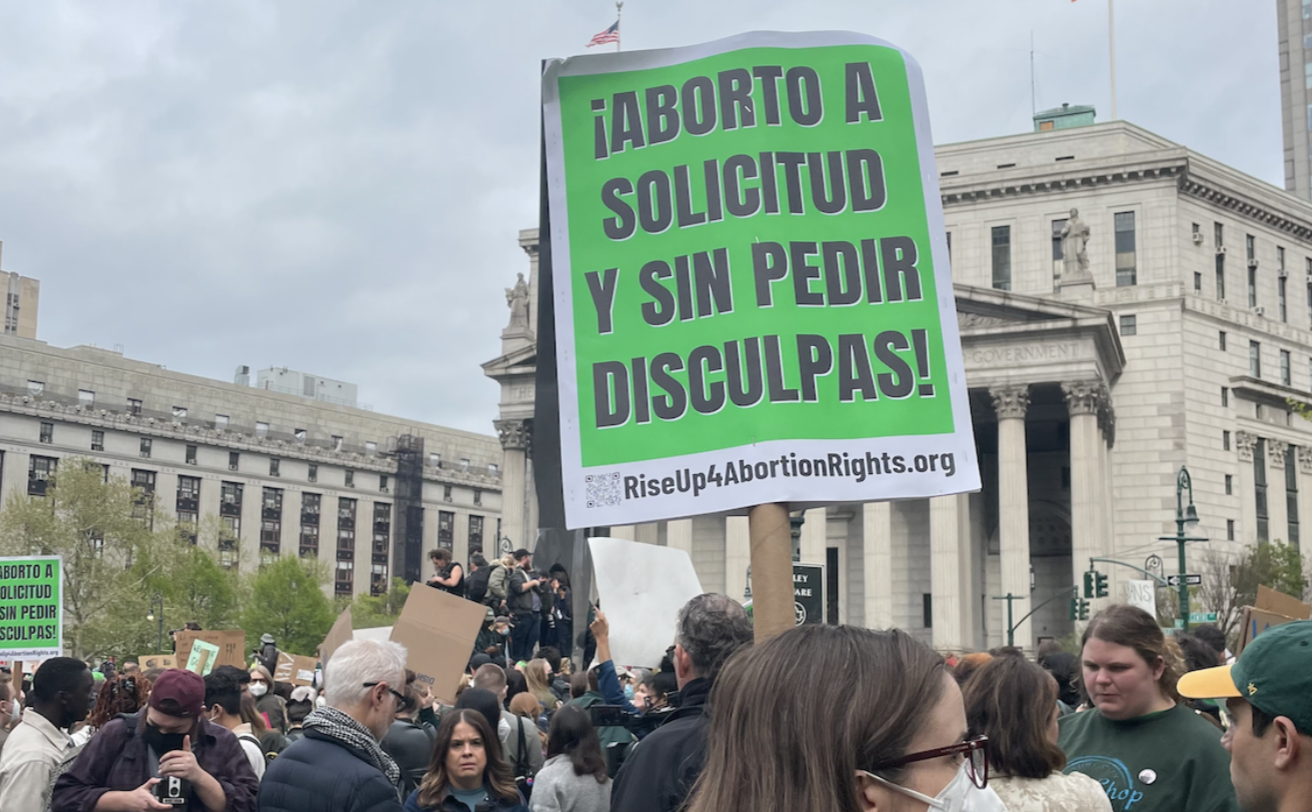

Protest in New York City after the leak was made public

Photo: Mariel Lozada

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate