Is Venezuela Doing Better?

Given that this question is becoming more frequent and is triggering more intense fights, we took a survey among our circles. What we found taught us a lot about how Venezuelan reality is perceived from the inside and outside

Photo: Sofía Jaimes Barreto

Venezuela changed. We’ve discussed this in several pieces that range from the political, social, and economic points of view. It’s a more assertive sentence than the infamous “Venezuela’s fixed” (Venezuela se arregló) that we see in memes and furious Twitter threads explaining why Venezuela isn’t fixed, or that the sentence is sarcastic, or that it’s government propaganda, or that it isn’t fixed, but that there are opportunities.

However, the perception people have about this change grabs our attention. That’s why we decided to do a simple poll, online, to try and understand some of the staples considered by Venezuelans when they say that the country has improved (or not).

How did we do the survey?

We designed a short Google Forms questionnaire, looking for closed answers only, which we distributed around social media. Since we accepted answers from anyone who wanted to participate (voluntary sampling, as it’s called), we should state clearly that the results don’t represent the opinion of all Venezuelans. The results are, as such, a reflection of the beliefs of a fraction, those who frequent Twitterzuela, Instagram, and readers of Arepita and Caracas Chronicles. A rather relevant sample of our bubble, that, while limited, has yielded interesting results.

How many answers did we get?

Between March 8th and 21st, we received 436 answers from Venezuelans, 322 living in the country (42 years old, on average) and 114 living abroad (37 years old, on average). Around 60% of the polls were answered by men. All the questions in the poll had to be filled, so all participants had to answer the entire questionnaire to have them registered.

Is Venezuela doing better?

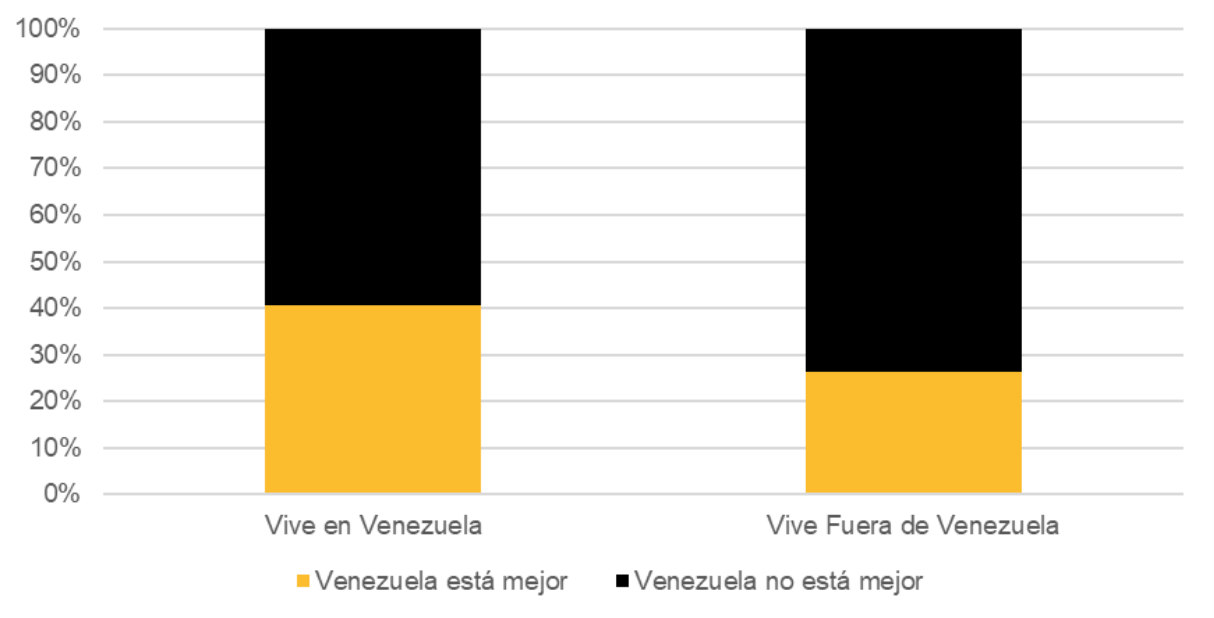

“Is Venezuela doing better?” was the general question we began with. Before going into the minutia, we wanted to know people’s general perception.

On average, both those who live in the country and those who live abroad don’t think Venezuela is better now; this opinion is shared by 59% of the participants living in Venezuela and 74% of those who live abroad. The margin is noticeable.

Among those who think Venezuela has improved, people living in the country are a lot more optimistic (41%) than the diaspora (26%). We should point out: many people who live in another country answered “I don’t know” to several measurements polled, so the number of opinions in those areas was smaller.

Has the situation in Venezuela improved? Not so much, according to Twitterzuela

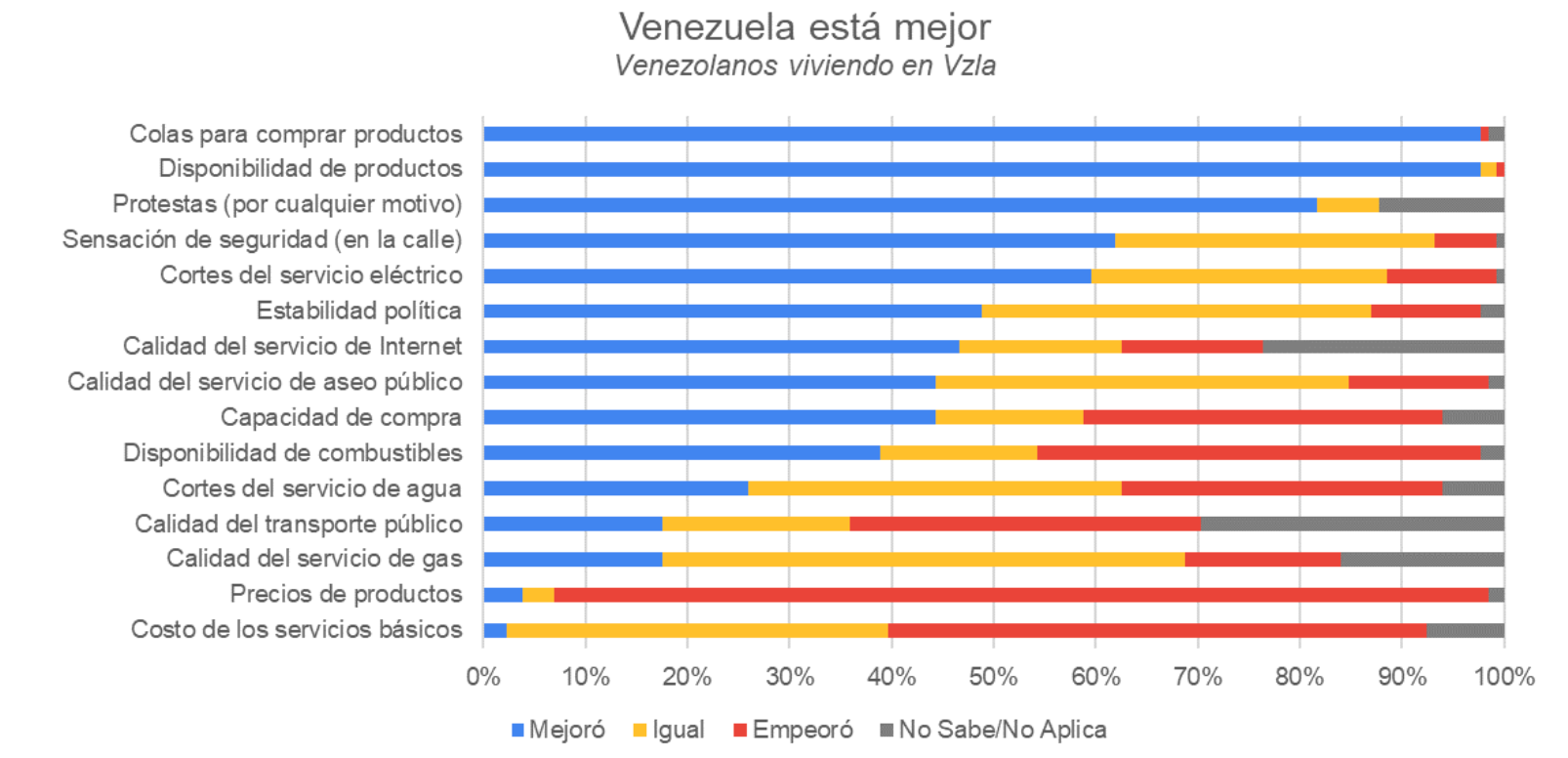

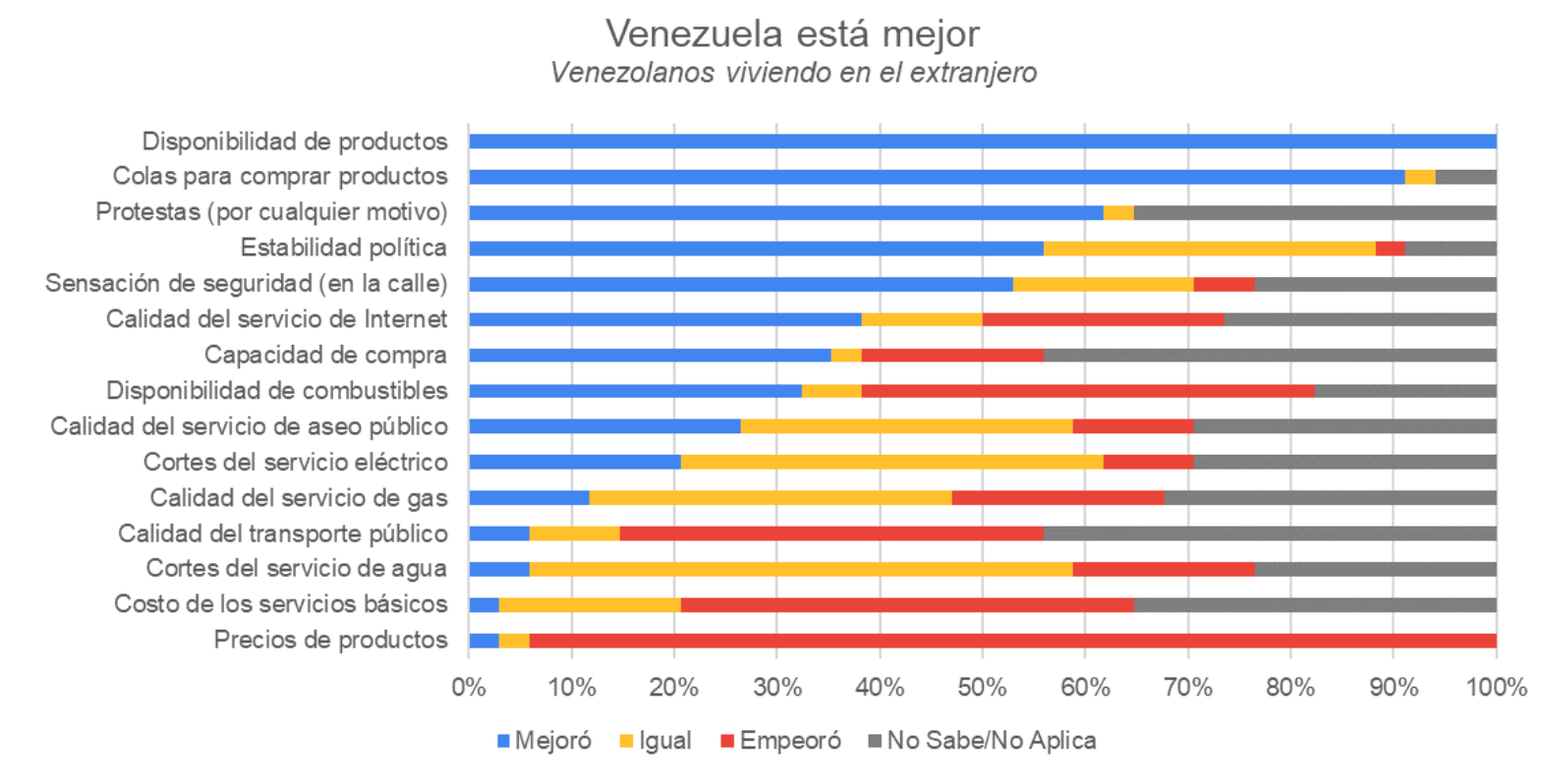

Which measurements seem to drive the thought that “Venezuela is doing better”?

For Venezuelans who feel things are improving in the country, whether they live in the country or not, the first three measurements were the same: decrease in lines to buy products, more availability of those products, fewer protests. It’s not surprising that those who live in Venezuela claim improvements in public services. It stands out, for instance, that those who live in the country feel the electric service has improved significantly, way above those who live abroad.

Venezuelans in Venezuela

Venezuelans abroad

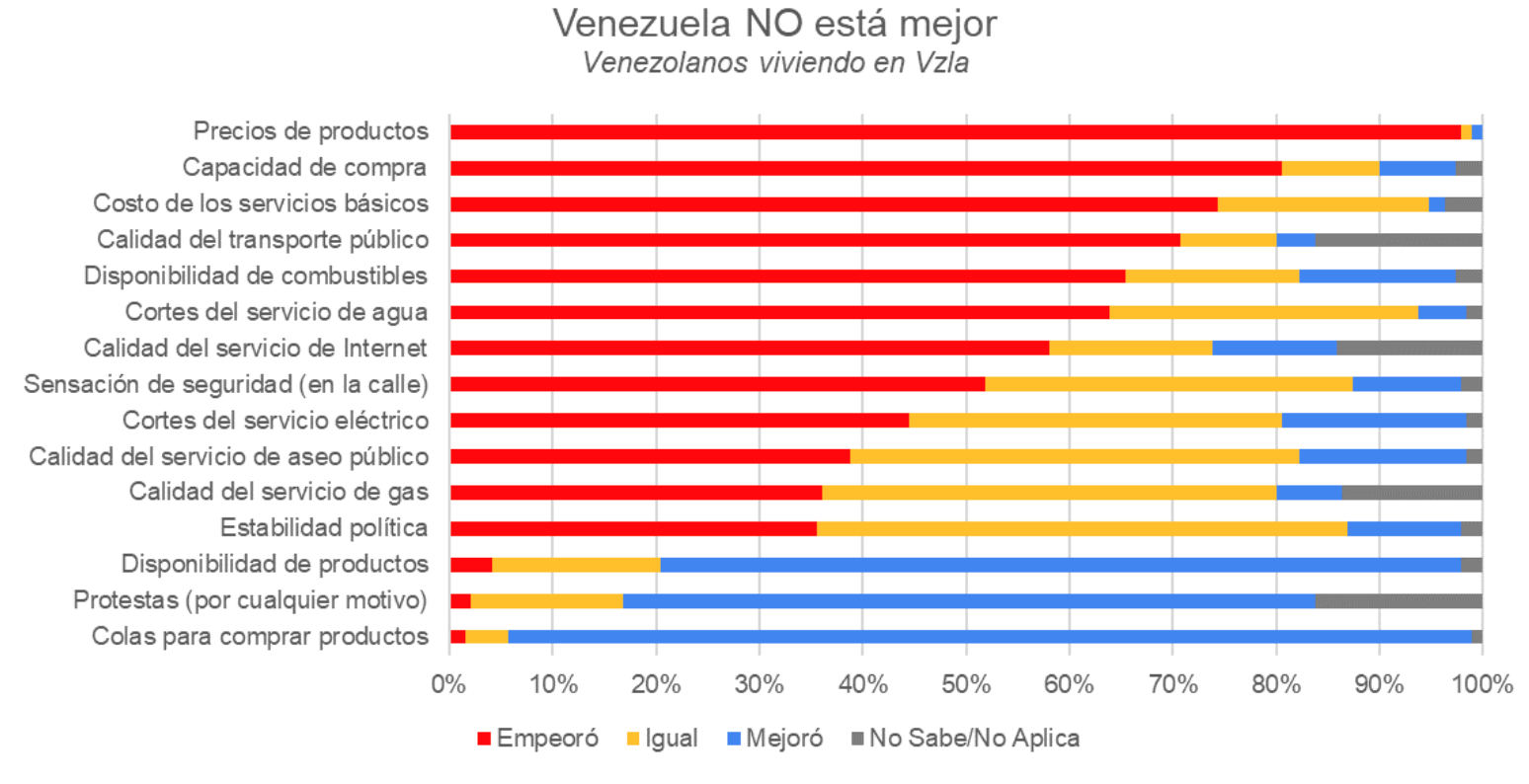

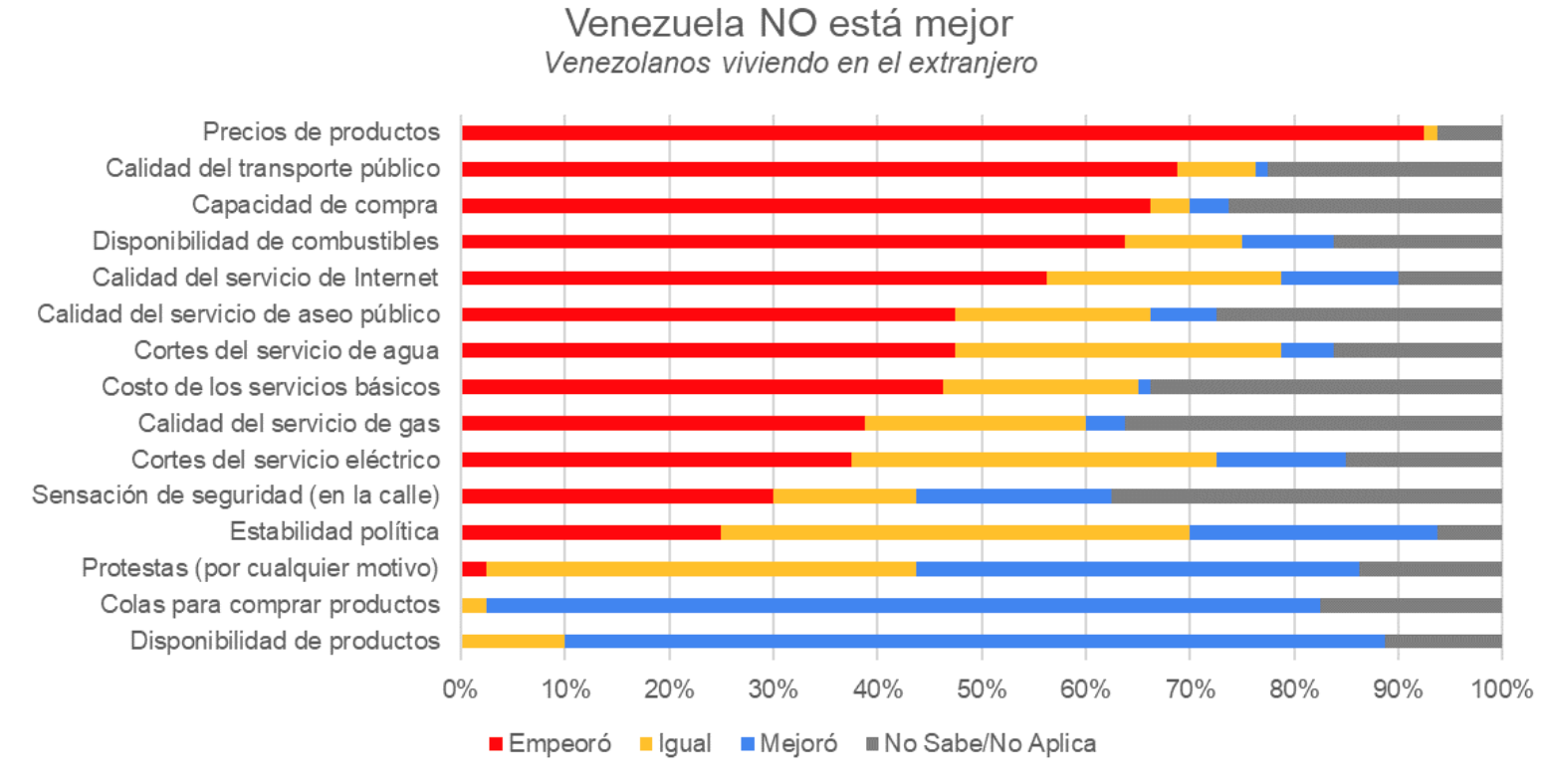

Which measurements seem to drive the thought that “Venezuela hasn’t improved”?

For those who believe the conditions in the country haven’t improved, the measurements which have worsened are linked to the cost of living and purchasing power, followed by the quality of public services. For those who live outside Venezuela, the items that have remained “same” are fewer and they point to a major improvement in the decrease of lines to buy products and greater availability of items on the shelves.

Venezuelans in Venezuela

Venezuelans abroad

What do we think of the results?

Those of us who live in Venezuela have noticed improvements in product availability (the well-known “you now find everything”) and a boom in commercial services. However, there’s another problem now: we can’t afford it.

Regarding services: there’s a feeling of improvement in residential electricity supply, which may be the result of a decrease in productive and commercial activity during the pandemic. Also, after the pronounced shortage of fuel at the beginning of the pandemic, the situation has been normalizing, as long as you can pay international gas prices. Other public services haven’t registered notable improvements, which has opened the field for private service endeavors: transportation services, like Ridery and La Wawa; an important growth in internet service providers; growing number of water tank trucks, among others. On the political front, Venezuelans feel certain stability, because of several elements (whose weight wouldn’t be trivial to measure): internal political exhaustion and diminishing international pressure; social exhaustion because of confinement policies; decrease in the government’s economic intervention; among others.

The Time-Away Effect

If it’s true that distance gives people perspective, it’s also true that with distance people lose grasp of the details. And this is revealing when we look at the answers given by those of us living abroad about the availability of products and services. But broadly, there are also some subjective elements, which can lead a migrant to answer these sorts of questions with a certain passion. Those elements go a bit further than the idea of needing to justify having left, while facing a Venezuela which, come may feel, is being violently marketed to them (as if it were an NFT). That is one way to over-simplify the external view, which ignores the reasons why many people left and why they don’t look back without a second thought. On the other hand, we’re also ignoring what those abroad live through their families back home, the anguish to raise the money to pay for medical expenses, which has gained quite a lot of visibility in social media.

Now, beyond empathy, the reality is that it’s no longer about the difficulty of seeing the present from afar. Beyond the distance, the time factor becomes an influence too. A lot of people left at a time when there simply was no food, a time when people would complete a bowl of soup with water and salt. A time of sheer hunger. Because of this, reactions of those who briefly come back to Venezuela sometimes resemble reviews in a tourist pamphlet, because the contrast to what 2018 was like, for example, is significant. We know that social media amplifies content that generates strong reactions and what we see there hides the perception of those who aren’t on Twitter or Facebook. But just the same, inside the group of us who might think that the general opinion is that Venezuela has improved, the prevailing opinion is that we’re still stuck in the mud. And if we’re talking about perceptions, there are other kinds of realities that aren’t measured and don’t have as much presence on social media.

The Inside-Outside Gap

This small sample that we see in the survey, is the reflection of a larger conversation that we must have: each day, there are more substantial differences in the way the country is understood by those who live in Venezuela and those who live abroad. We’re not saying that one way of understanding it is better than the other, but it’s time we analyze our own public opinion according to those realities.

One of the ways we see these differences in the country’s perception is, precisely, how we determine whether material life conditions have improved or not. As expected, there are nuances that can only be appreciated by those who actually live in Venezuela: from higher water pressure, to what it means to be able to choose between two or more brands of rice. For those living abroad, it’s very difficult to perceive these changes, and it would be unfair to ask them to.

But these differences in the country’s perception might only be an anecdote if they weren’t setting the pace in the way political dynamics are understood. It might be worth it for experts to study the differences that are becoming clearer in terms of how the political dynamics should unravel for those who live in Venezuela and for those who don’t. All the conversations about the caretaker government, taking part in elections, and participating in political negotiations, are influenced by opinions posted on Twitter by those who live in Venezuela and those who live abroad, and the different positions are becoming thornier.

This is why perceptions are more important than they seem. There were several discussions recently, also aired through the limited terrain that is Twitterzuela, focused on the possible numbers for economic recovery for Venezuela in 2022. The most optimistic projection, which for any Venezuelan (in the country or abroad) will sound over the top, projected a 20% growth of the GDP (Credit Suisse). In the discussion, we saw several points of view, by experts like Asdrúbal Oliveros and Francisco Monaldi, where that hypothetical recovery was compared to other less optimistic numbers, but positive still, and numbers before 2012. Assuming that Venezuela managed a sustained, two-digit recovery, it could take around nine years to get to where we were in 2012.

And even if Venezuela did get a two-digit recovery (let alone 20%): what will people perceive? Frankly, we doubt that in a recovery scenario, people—except those of us whose work is to keep this infamous record updated—will be thinking of Venezuela in the ‘90s, for example. Especially those who didn’t live it, particularly the three generations used to seeing everything getting worse, day-by-day, since the ‘80s. How that perception is handled will be very useful for those who know how to use it.

Special thanks to @soyarepita for sharing the survey with its readers.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate