The Elastic Families of Venezuela's Forced Migration

Some have been stretched out so much that they’ve broken, others are reuniting abroad, and some others have been replaced by community networks. This is how the family is changing in Venezuela

Photo: Composición de Sofía Jaimes Barreto

It’s January 8th, 2022. A Venezuelan traveler who just landed in Cúcuta from Bogotá, where he arrived from Madrid, reaches the border by taxi. A swarm of young boys surrounds the vehicle as it stops next to the Simón Bolívar International Bridge. They’re skinny, of all sizes and colors, some are wearing shorts and are shirtless. They compete to convince the traveler that they’re not there to rob him but to help him cross the bridge without forgetting the migration pre-registration that Colombia requires to stamp your way out and so the National Guard won’t check the luggage on the other side.

“The police hasn’t been able to handle those kids from your country,” says the Colombian taxi driver as he gets paid for the ride. The word “criminal” gets stuck in his throat. They took over La Parada, they rob and kill themselves, every day. A police operation of about two hundred cops is needed, but then they start with the whole human rights issue and everything stays the same, or worse.

The traveler, a lawyer with experience in human rights, remembers the ancient Venezuelan police practice of forced migration as he gets out of the taxi and three of the boys take his suitcases. “Let’s go and get your passport stamped, it’s this way,” they say with the suitcases already on top of their heads, pushing people away. In front of the railing that protects the immigration office in La Parada, the Colombian policeman tells them “too bad, you can’t go through.” The boss is there and he can’t risk it.

The boys step aside and the traveler goes forward by himself with the suitcases, while they yell instructions from behind the railing: Turn left! It’s the second door! When the traveler drops his luggage on the corner of the hallway that leads to the immigration employees’ cubicles, the boys yell “we’ll look after your suitcases, don’t worry!”

The procedure is quick. “Take your bags!” the guides say. Before they reach the exit, the luggage is once again on their heads. They say that they only want something to eat. The traveler asks them where they’re from. “From La Guaira,” says the quickest one. “From Caracas,” says another. The tall, slim one with red eyes doesn’t say anything. He’s carrying the largest suitcase. The traveler only has 20,000 Colombian pesos. The quick one says it’s 40,000.

The slim one puts both suitcases in a sack and swings them over his shoulder. He’s the chosen one to accompany the traveler to his country. The other one, without a shirt, can’t go. The slim one says that he’s been sentenced by the FAES: “If he crosses over, they kill him.”

The slim one’s name is Henry and he’s local, from San Antonio del Táchira. He says that it’s best to wait until the GNB officers are busy checking other people’s bags, and if they ask, don’t tell them that you’re coming from Bogotá, not to mention Spain, “because they’ll rob you.” That’s how they do it; they go forward when the guards are checking other travelers. A couple of blocks after the bridge, at the Venezuelan bus and taxi stop, Henry says “that’s it, you were lucky.” He takes the bags out of the sack. He mentions the poverty his family lives in and asks for 20,000 more pesos. He insists without being aggressive, with sadness, and hunger. The traveler takes out his last ten thousand pesos. Henry resigns himself, says thanks, gives a few blessings, shakes hands, and leaves.

The traveler remains moved and stunned for a few seconds until he takes out his phone to call his brother, who’s waiting for him in the car to take him home.

…

Those boys, as well as most of the people they offer their services to, are caminantes: people who migrated on foot. Not far from that bridge, in the city of San Cristóbal, researcher Rina Manzuera, from the Observatorio de Investigaciones Sociales en Frontera, has been interviewing caminantes in the last few years. Among them are very few elderly people, for whom those long and dangerous journeys, sometimes only wearing sandals because they don’t have other shoes, are impossible to undertake. Lately, there are more children leaving with their parents, but also more minors coming back, because their parents can’t have them in another country, or because they need to get their papers in order to be able to enroll them in school in the host country.

“We’ve had cases with some adult travelers, that when we ask them what’s their relationship with the child, they say: ‘None, it’s just that we were walking and the mother stayed in Colombia working and she asked me to bring him to Valencia and to hand him over there.’ So, it’s not that the risks for children are decreasing in international migration,” ” Manzuera says.

In Caracas, NGO Aldeas Infantiles SOS began working years ago with UNICEF and Redhnna so that families who were thinking about migrating knew about the risks for the children they were taking with them or leaving behind, as well as the documents they had to process so that those children could connect with the identification, health, and education systems in their new countries. In UCAB’s Centro de Clínica Jurídica, María Fernanda Innecco remembers the increase in the power of attorney requests four years ago, so grandparents could represent the children who have stayed under their guardianship in the communities in southwestern Caracas.

Read Part I of Los Migrados: When You Uproot Your Entire Family Tree

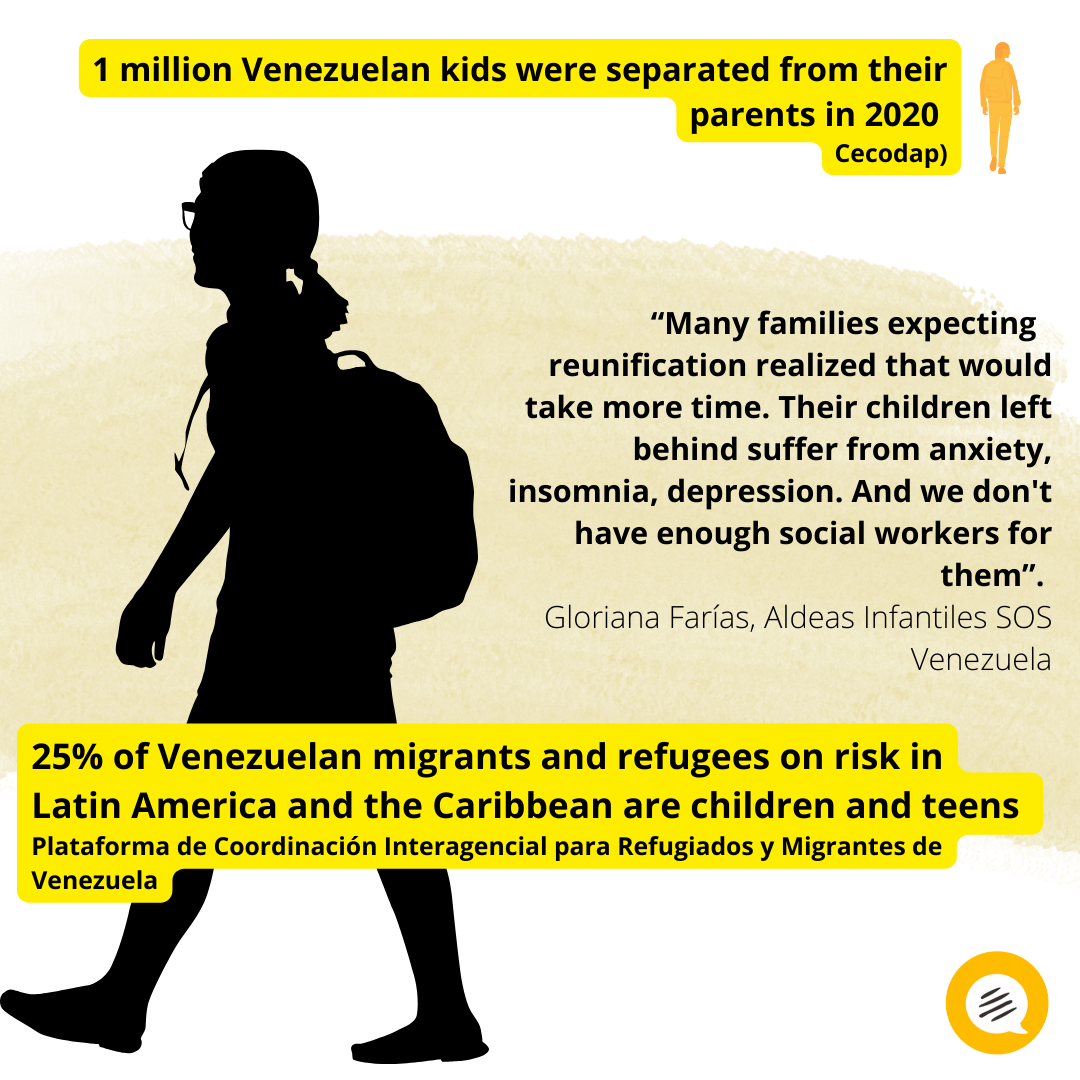

Since then, families have been learning and following the formal steps available today; another sign of maturity in forced migration. But many girls, boys, and teenagers are still in danger: those separated from their parents, and particularly if they were left unaccompanied, with no one to take care of them in Venezuela. Kids that, in some cases, take off on their own to try to rejoin their parents abroad. In Boa Vista, Brazil, there’s a shelter for these unaccompanied minors, where they can stay until they turn eighteen… and then they’re adrift and alone in a foreign country.

Trapped by the tension of finding a source of income outside of Venezuela and being close to their children, some migrant parents see the region bordering Colombia as a place of hope. Rina Manzuera has seen how schools in Táchira—the state that connects with the more crowded border pass to Colombia—have been receiving children from all over Venezuela, who have been staying in the region to be closer to their parents, who work on Colombian soil. In the Venezuelan towns of San Antonio or Ureña, those parents can sometimes visit their children or pick them up to take them away when the time is right, and in the meantime, someone takes care of them. It’s like a halfway stage between having the children emigrate and keeping them in the country, but still with high vulnerability because of the economic instability of their migrant parents and their capacity to protect them. That mother in Colombia who has to send a remittance is at the same time struggling to pay rent and not starve to death. “When you take a look at how they eat that day, many family solidarities which used to bear the social fabric, wane,” Manzuera says.

In the traditional Venezuelan family, everyone has a role to play, Manzuera says, and although there’s poverty in general, there are two or three people who can provide for the group so that the children can stay in school and not work. But with forced migration, the mother may be gone and there are many children being looked after by their older siblings, grandparents, or even neighbors and then the expectation is to get by day by day; those kids’ future development, in the long term, is out of reach for those surrogate parents. According to Manzuera, “one family left their daughters to be cared for by someone in Cúcuta and the girls ended up returning to Venezuela because they were sexually exploited in Cúcuta.”

Carlos Rodríguez, a researcher for UCAB’s Centro de Derechos Humanos, says that families began to disintegrate in 2016 because a member of the household decided to emigrate. “We saw siblings separated: the youngest stayed, the oldest left so that he could help the parents in the other country. Or teenagers between the ages of 12 and 18 years old leave on their own to send money to their families in Venezuela. There are also reports of entire families who leave and lose their children on the migration trail; because they stay behind, they’re recruited by armed groups or kidnapped. In Colombia, on the Pamplona route, if a family of caminantes is offered a ride but they don’t all fit in, they send their children ahead and tell them ‘wait for me in whatever-place’ and the child gets lost or is a victim of abuse.”

…

It’s been said many times before and it’s still thought to be true: the Venezuelan family revolves around a mother and her capacity to solve the survival challenges and the progress of each member of that core. That’s the way it’s been since colonial times, according to Mirla Pérez, from the Centro de Investigaciones Populares: “But this migrant emergency, this moment of rupture in the history of Venezuelan society created by a political movement, generates consequences in that matriarchal family.”

Which consequences? “Forced displacement, in any culture, can be very difficult, but in the case of Venezuelan culture it’s very painful, because the only existing strong link is the cultural relationship between mother and child, and what we’ve seen here is a mass departure of sons and daughters,” says Pérez. The larger portion of migrants is between 19 and 40 years old. The wealth of a family is its children and when they leave the family is left unprotected, defenseless, especially the mother, although the Venezuelan mother is very autonomous.”

The Centro de Investigaciones Populares has documented internal displacement and even depopulation, especially in Zulia. They saw family units where the head of the family was a twelve-year-old boy. But they’ve also seen families that reunite, both in the country and abroad.

A good national census, which we don’t have, could tell us how forced migration has altered the family ways: how many have left and who has taken their place, how that family has changed in numbers compared to what it was before migration. What we do know, as it’s been commented in the Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida (ENCOVI) and what Mirla Pérez also says, is that so many Venezuelans in their productive age have left that Venezuela has lost its demographic dividend, that historic window of opportunity where a nation has a high ratio of young population, whose productive energies have to be harnessed to make the nation leap into development. After being a country with too many children and teenagers at the end of the 20th century, we were reaching that demographic dividend in the 21st century when educated youths abounded, the right moment to make the collective effort to overcome poverty and progress. What we had instead was a collapse in every aspect and the most violent migration in contemporary history that didn’t involve a civil war.

For Alexander Campos, another researcher for the Centro de Investigaciones Populares, demography is essential but it can’t completely describe the magnitude of the transformation that such a sudden and extended migration has caused in Venezuelan society. We’d need a study on the impact on family structures.

Gloriana Farías, of Aldeas Infantiles SOS, believes that there’s been a turnaround in these structures, with so many grandparents or older brothers having to take on the role of raising the smaller ones, for which they aren’t prepared. Young people who can’t study anymore because they have to take care of their siblings, and grandparents whose ailments from old age, the shortages and a tight budget in retirement have to now add the hard task of raising a child. Mirla Pérez thinks that the Venezuelan popular family “has had to reconfigure itself.” Campos says that the mass migration phenomena don’t usually change the family structure, and they shouldn’t in a country where the experience in internal migration from the fields to the cities, present in generations of living Venezuelans, created tiered migration methods: a man or a woman or a couple would leave first to where there was work, leaving the kids behind with grandmothers, and the children would join them, and sometimes those grandmothers too. Unlike European migration to Venezuela in the 1940s, mostly led by men, the domestically migrating Venezuelan family that has the mother as the center, would stretch out as it moved around the country, but it didn’t break, because grandmothers would substitute the mother whenever it was needed.

Today, however, this tradition of the surrogate mother during migration periods, which helped so much during the demographic transformation in the 20th century, has found the limits of its reach; because this Venezuelan migration in the middle of a brutal economic crisis left many children in the hands of their grandparents, who don’t have the material capacity or physical health to protect them adequately.

The good thing is that right now, according to what Campos and his team have observed in the communities, is that a new chapter in our history is beginning. “The migration wave of 2014 to 2018, which was made up mostly of poor people, from popular areas, was a migration of isolated subjects, alone,” the researcher says. “Once that migration has occurred, what we’re seeing right now in 2021 and 2022, is that families are being rebuilt.”

Read Part II of Los Migrados: How Violence Separates or Displaces Venezuelan Families

During the pause of the migration flow to other countries imposed by the pandemic, thousands of migrants had to return to those Venezuelan towns in the east and west, where you would see many children under the care of their grandparents who couldn’t afford to provide for them. As borders and regional economies have started to reactivate, and with them the migration, those migrants who had returned are leaving again, but now they’re taking their children with them, and if they can, the elderly too. Struggling families which had stretched thin in 2018 are reuniting, not inside the country, but in a second phase of the forced migration, in which there’s more experience about what’s going on outside, where to go and how to go, there are more people abroad who can help with the arrival, and therefore, a better chance to take the children, the elderly, and even the dogs.

“There are families reuniting abroad,” Campos says, “and those who’re staying in the country, do so with the hope of being together again because migrants never meant to leave their families alone forever.”

…

Without demographic studies that can provide us with numbers, but having focal groups which generate a large number of stories, the Centro de Investigaciones Populares is following communities in Lara, Carabobo, Táchira, Falcón, Sucre, Zulia, and Bolívar. They’ve seen that returning migrants are welcomed back with joy or understanding when they’ve been expelled from their destination because they couldn’t legalize their status, but in reality, most of those who have returned have tried emigrating again or plan to do so as soon as they can. Not only do those who return realize that there aren’t conditions to stay in Venezuela, but their parents and grandparents have understood in several cases that things won’t improve in the country and they’re more willing to handle the cost and take the risk of emigrating too: “They’d rather spend the last years of their life with their family together abroad than living the last years of their life alone because they’re realizing that their family members are less willing to return, With time, Venezuelan migration will become more of a family affair and we’ll see fewer children left behind,” Campos explains.

The emergence of this reuniting pattern, usual in other diasporas and distinguishable even in histories of migration into Venezuela from families rejoining from Palermo, Madeira, or Tenerife, isn’t the only finding by the Centro de Investigaciones Populares. “I understand that this family separation can cause a lot of fear among those who are worried about society, because if we make a lineal projection, it’s a catastrophe, the complete social disarticulation, everyone going their separate ways. But some very interesting phenomena are happening, which tell not only about the mentality in Venezuelan society, but of how societies look to survive in their hardest moments. And we see that in a social learning we’ve witnessed across the country: neighbors,” says Alexander Campos. According to Mirla Pérez, “culture is filling the gaps that forced migration is leaving behind, but the shadow of the absent family is still there. We’ll have to see what the long-term effects will be.”

Campos talks about how in communities where the 2017 shortages caused an every-man-for-himself type of environment, spontaneous solidarity networks have emerged today, like in a building or a block of houses, where groups of neighbors take on the protection of the most vulnerable, which used to be done by the families of those people when they were in the country. For him, that’s much more valuable than the remittances.

“I don’t know where the myth came from that remittances are the ones supporting Venezuelan society. Our research shows that the families who receive remittances only get around 40 dollars per month, and that decreases if the one who stayed behind is a father and not a mother, to which there’s a larger obligation and she distributes it to the entire family. CLAP bags cover more ground in the popular neighborhoods than remittances. They don’t really last for long either, of course, but it’s better than nothing. In fact, there have been cases where mothers in Venezuela end up sending a few dollars to their unemployed sons abroad.”

In a study between 2015 and 2021, Aracelis Tortolero, from Centro Gumilla, found that remittances don’t come in regularly, they’re sent when possible, and they have to take into account the difficulty to exchange the money or to transfer it in Venezuela, especially before dollarization and more companies entered the market to send packages here from the host countries. Tortolero points out that medicines are also considered remittance. But in economic studies, “remittance” only refers to money sent from abroad.

From her observation post in the middle of the walking travelers’ route, Rina Manzuera doesn’t believe remittances sustain families in Venezuela either. In fact, she’s seen migrants coming back because they can’t even support themselves abroad. “Remittances also have an important symbolic value, the message is that I haven’t forgotten you,” says Mirla Pérez.

…

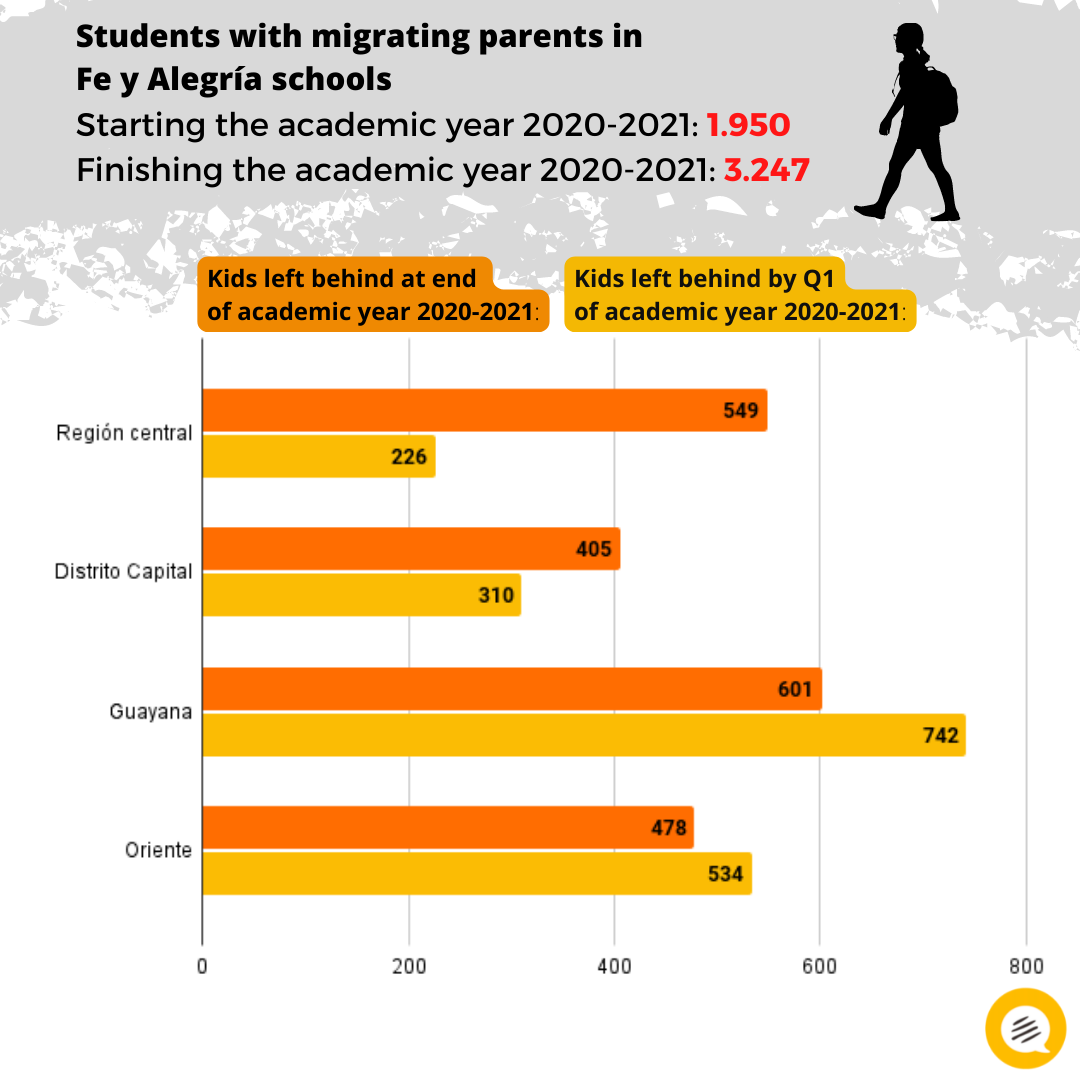

Fe y Alegría operates in 19 out of 23 states in Venezuela, and they’re a good reference to see how many children are being taken care of in the most disadvantaged areas. The national coordinator for citizens of this institution, Yameli Martínez, says that since 2018, and in spite of the return of migrants during the confinement months with the pandemic, they don’t stop seeing how children are left behind to be taken care of by their relatives. And the children with best attendance records, behavior, and school performance, are usually those who’re still with their families or have good caretakers.

Fe y Alegría

Teachers in Fe y Alegría have found out that some of these kids have reunited with their parents abroad, but others are still in Venezuela because their parents don’t want to expose them to the risks of the journey or aren’t financially ready to take them away. Those minors who are left behind can go through changes in their behavior, which then puts them at risk of repeating grades or desertion, or mistreatment and abuse where they live. For Martínez, “those who are perceived as a burden for their caretakers are the most vulnerable and run the risk of not being properly taken care of or protected in their basic needs.” And there are things that aren’t mentioned: “We had a student who, apparently, committed suicide because her parents left the country and they left her with her grandmother.”

…

As well as the source for learning rules of coexistence and role models, a family is a safe space so that each person can build their own self, Rina Manzuera points out. “Then all of that moves on to a larger group, which is society. But if the family isn’t performing their duty, beyond the arepa and coffee that an NGO or the State can also provide, we have a big challenge as Venezuelans: how can we help those families function again. Because a society can’t function if the family doesn’t. That’s the damage this migration is causing. How many grieving families are there? How many have left? That’s Venezuela’s real loss.”

“We went from being a young country to an old country in eight years,” concludes Mirla Pérez. “Europe prepared for that, but Venezuela didn’t, and that will bring consequences. In cultural terms, the family foundation will still be there. The issue lies in the impairment of living conditions and the bare capacity to provide, to work. But there’s still productivity and room to strengthen the traditional social fabric. Our own cultural mechanisms that so far have prevented the entire social fabric to fall apart, will keep working in dire situations.”

You can find a Spanish-language version of this article in Cinco8.

Read Part I of Los Migrados:When You Uproot Your Entire Family Tree

Read Part II of Los Migrados:How Violence Separates or Displaces Venezuelan Families

Los Migrados was made with the support of Factual.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate