How the Russian Invasion Affects Remittances from Venezuelan Migrants

Hiking prices of gas and food in the countries home to our migrants, where the global inflation is already cutting expenses, will compromise the amounts of economic to send to Venezuela

Photo: HRW

To the dangerous combination of dollar prices increasing in Venezuela and global inflation slugging economic recovery, we must now add the impact that the Russian invasion of Ukraine will cause in a migrant’s capacity to send remittances back home—once the impact of the conflict in items such as gas, power, and food is felt in the coming weeks and months.

Russia is not only a big oil and natural gas exporter, but also—like Ukraine—an important producer of cereal. Extracting these commodities from regular markets will cause an impact on the global supply and, therefore, an increase in their international prices—also consider the worrying inflation the world is experiencing since the final months of 2021.

Recent data from the OECD (which has among its 38 members some of the main destinations of Venezuelan migrants, such as the US, Colombia, Spain, Chile, Italy, and Portugal) says that the consumer prices recorded by the organization were 7.7% higher in February 2022 than in February 2021. This is the highest year-to-year average inflation in those countries since 1991.

Car owners in Canada and the US just saw the price of gas hiking over 4 dollars a gallon while the news from the horrors in Ukraine filled our screens. The pandemic-related supply chain disruptions were already increasing the cost of food.

Europe is obviously more vulnerable, in the short term, to the sudden interruption of gas supply from Russia: “If the price of energy hikes in Europe, we can expect that remittances sent by Venezuelans from Spain, Italy, and Portugal, among others, will be impacted. The same will happen in Latin American countries that import oil, such as Chile and Peru, or even Mexico, which imports gas from the US,” explains economist Manuel Sutherland.

Global migration has many economic impacts; remittances are amongst the most important. And chavista policies have turned Venezuela from a country that sent remittances into one that needs them as part of its national income.

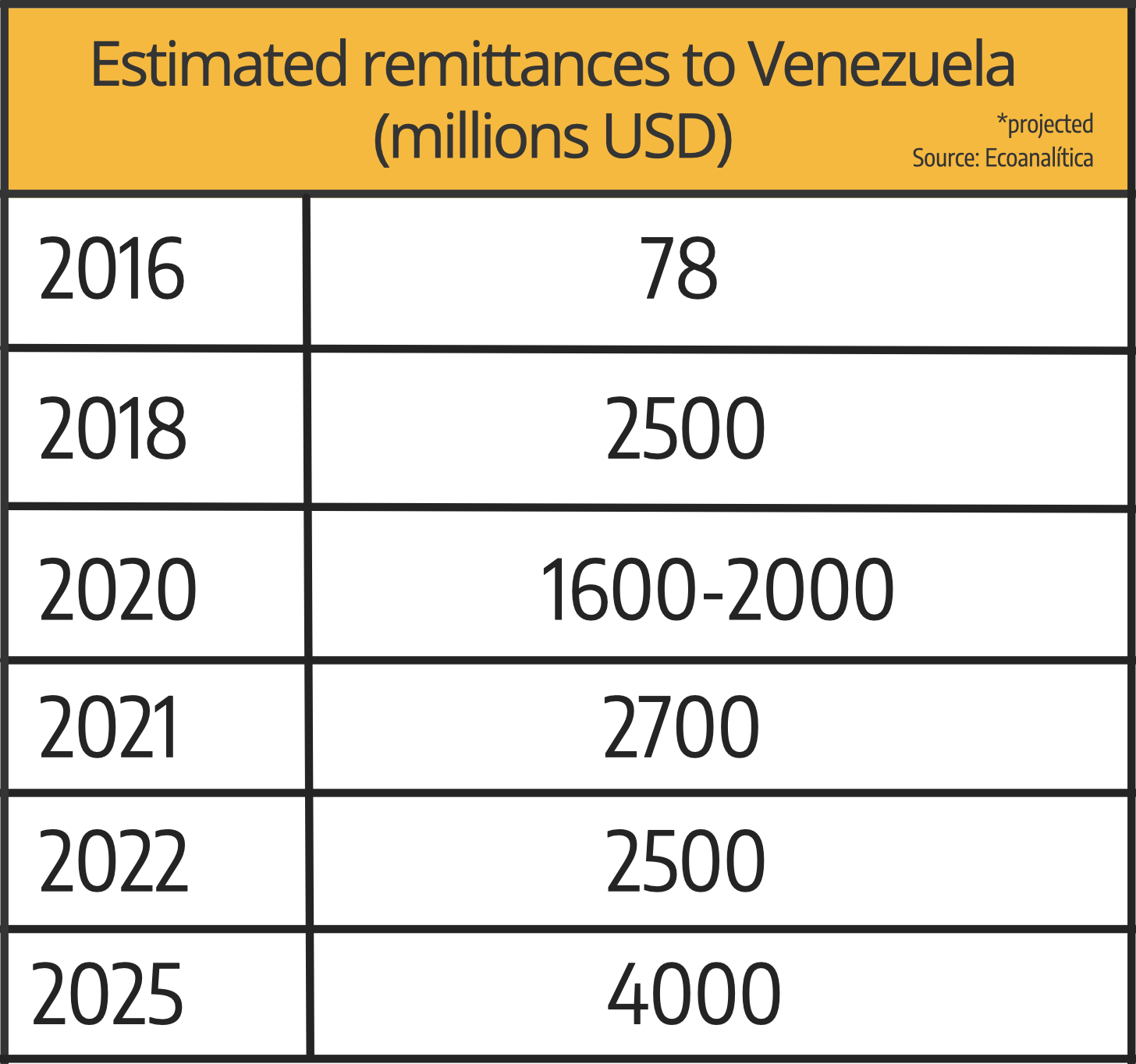

According to the consulting firm Ecoanalítica, remittances in Venezuela went from 78 million dollars in 2016 to 2.5 billion dollars in 2018. They fell in the pandemic and in 2021 were about 2.7 billion dollars (equivalent to 6% of Venezuela’s GDP). Before the war in Ukraine erupted, Ecoanalitica had projected 4 billion dollars for 2025.

Remittances are so important that, according to the World Bank, in low and mid-income countries—excluding China—they amount to more than all direct foreign investment and development aid. Eonomist Michal Rutkowski says remittances must be critical in the design of any economic recovery policy in the world, especially after the pandemic and now the war in Ukraine.

Latin America and the Caribbean would have received 126 billion dollars in remittances in 2021, according to World Bank numbers, which is an increase of 21% over 2020, driven by the migrants desire to protect their families from covid and unemployment (a similar trend was shown by all other regions that receive remittances, with the exception of Asia, where the economic impact of the pandemic was lower). 42% of those remittances went to Mexico, and in countries like El Salvador, Jamaica, and Honduras remittances are up to 20% of the GDP.

In the specific context of Venezuela, we also have sanctions. Before the much-commentated trip to Caracas of an exploratory delegation from the Biden administration, economist Ronald Balza told Caracas Chronicles that Maduro’s public support to Vladimir Putin would diminish the chances of getting some sanctions lifted by the U.S. and its allies: “Venezuela already had big economic problems. Just when we get out of hyperinflation but with a very reduced economy and population, this war will affect our capacity of recovery, even with higher oil prices and a bit more export income. We just have too many problems and need too much international assistance.”

With the current weak oil-producing capacity, the chances of Venezuela resisting a reduction in remittances look thin.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate