How Venezuelan Preschools Turned into a Problem

Social and economic collapse, in addition to the lockdowns, have made early schooling another source of trauma and inequality

Photo: La Razón

The promise of early childhood education has been one of prosperity and equality. Time and time again, studies have shown that high-quality early childhood education can provide underprivileged children with the habits and opportunities that they need to get through school and overcome poverty. This was the very promise that inspired Venezuelan policymakers to implement a universal childhood education program in 1970, one of the first early childhood programs in the region. While the early childhood program’s expansion has been undermined at times by quality problems and lack of funding, the fuel crisis, low wages and supply problems have all but destroyed the program’s ability to fulfill its promise of equality and education for all.

“Teaching used to be my dream, but now I wake up every day and reexamine my choices,” says Ana, her voice echoing against the emptiness of the rooms where we stood.

Ana, whose name has been changed to preserve anonymity, heads a public preschool in the outskirts of Caracas that has been struggling to stay afloat throughout the crisis. The preschool, the only one of its kind in this rather rural area, usually serves 80 children ages two to six.

My visit to the school coincided with the government’s decision in April 2021 to maintain a “radical lockdown” system as the result of an increase in cases. As we walked through the school, I took note of the colorless walls and empty shelves and Ana responded by assuring that the lockdown had enabled the school’s further abandonment. The government, whose competency it is to maintain this preschool, had provided no guidance to teachers with regards to how to handle schooling during the pandemic, leaving issues of maintenance, security and educational provision at bay. “I’ve been coming back here every so often, doing administrative work so that I can maintain things as they are and also to signal to others that someone is here so they keep out, but there are some things I can’t really fix.”

While Ana’s strategy had been successful at avoiding theft and preserving a somewhat adequate infrastructure, the emptiness of the rooms reeked of abandonment rather than simplicity. And in fact, limited resources had been affecting the school’s functioning even before the lockdowns. In early 2020, concerns about the rising cost of transportation and food coupled with stagnant wages had already begun to affect the school. Staffing concerns were affecting the school’s ability to enroll more students. “I had to turn away a few parents who wanted to enroll their children in preschool last year because I was short on staff and I must respect a strict student-teacher ratio.” Additionally, while the lockdowns meant that the school’s infrastructure and stocking issues would be completely ignored, it also served as a temporary solution to the imminent wave of teacher desertion and absenteeism crisis that was about to emerge as a result of the economic situation.

“The lockdowns that made classes virtual allowed teachers to save money on transportation and enabled them to supplement their income through side gigs,” says Ana. So while the lockdowns were harsh on teachers and students alike they were also the only thing stopping a complete collapse of the educational system. Thus, when the Maduro regime announced in September that schools would return to in-person instruction, Ana joined other teachers in denouncing the infeasibility of this measure. However, many of the complaints about infrastructure, school supplies and staffing issues were ignored when Maduro declared that October 25th would be the first day of in-person school in 19 months.

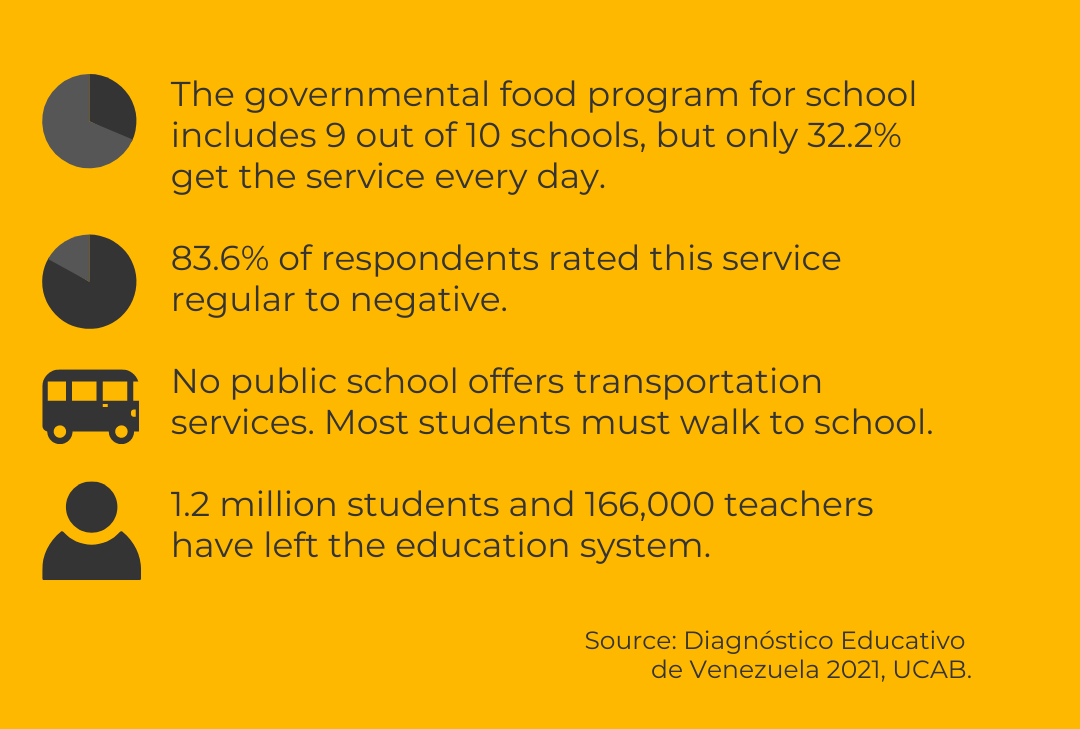

With the ongoing gas crisis and the rising cost of living, Ana reports that she had to reduce enrollments in the school as a result of staffing shortages and adds that while not all teachers have quit, many have begun selectively attending classes. She also reports that supply issues have affected the school’s ability to provide food. “We used to provide three meals a day: breakfast, a midday snack and then lunch, but in the past few years that food supply has diminished significantly,” Ana explains that food provision has been a challenge throughout the three years that she has served as head of the preschool. The promise of space for children to be protected and nurtured had inspired policymakers in the 1970s to open a preschool in the area, but this promise has become increasingly hard to keep amidst the crisis. The school’s inability to provide three meals a day for all students has also affected attendance. Parents, already struggling with the cost of transportation, often send their kids to school only when lunch is provided.

The Less Visible Effects

So while ideally, a preschool should be a place for children to learn, explore and develop a love of learning, the current circumstances might actually result in a more conflictive, less curious and more unequal generation of children. Preschool children need consistency and reliability in order to be able to develop healthy habits. This pertains both to interactions with other children as well as with teachers. Child development specialist Tracy Gleason highlights the importance of consistency in making friends: “When meetings with peers occur sporadically, it doesn’t allow children to bond very well and it might actually generate feelings of anxiety and abandonment in children and induce conflict.” Routines are also important for successful child development, she argues: “Being able to have a routine provides children with a sense of comfort that enables them to feel like they are in a safe environment where they can explore and learn.” On the other hand, Gleason argues stressful situations in school could contribute to feelings of inadequacy, poor socioemotional development and difficulty concentrating.

The relationship between teachers and students is also central at this educational stage. An Inter-American Development Bank policy analysis report establishes that having good teachers during early childhood boosts learning outcomes in all domains surveyed, namely cognitive development, math and executive functioning.

The best predictor of good teaching according to the study is high wages. It’s believed that a high salary increases teachers’ effort and it reduces desertion rates. In Venezuela, where teachers earn just under $7 a month, desertion rates have skyrocketed. A teacher’s consistency enables them to maintain better relationships with students.

Wendy Gonsenhauer, an early childhood education expert, highlights that teachers must be able to form valuable relationships with their students. Following Piaget’s theories regarding the inherent curiosity of children and Vigotsky’s discovery of the power of guided learning, Gosenhauer argues that children must engage in “scaffolding.” Scaffolding entails children freely exploring their interests and teachers supporting and propping them up with questions. In this sense, teachers serve to boost child learning and development while encouraging independence and freedom. Scaffolding, however, requires teachers to be informed on the interests of their students. “How are you supposed to know how to help them if you don’t know what they like?” says Gosenhauer.

Additionally, the IADB survey shows that setting clear expectations and providing feedback boosts children’s educational outcomes. Therefore, learning at this age relies heavily on the types of relationships children develop with their peers and with their teachers. This, in turn, defines children’s attitudes towards school in general. “A good preschool experience often results in more positive attitudes towards schooling in general,” Gleason claims.

Early childhood education is of vital importance if Venezuela is to overcome the present crisis. In the past, public education had served to boost social mobility in Venezuela. It was the opening of a public high school in Porlamar (Nueva Esparta) that enabled my grandmother to become the first person to attend college in her family in the late 1960s, even despite her modest upbringing. Public education also helped my godfather escape the slums of Caracas in the 1970s and graduate from the country’s most prestigious medical school in the 1980s. While Ana describes her school as having been a haven, a place where children could “play, make friends and exploit their curiosity,” the current situation has turned the school into another source of anxiety and stress for young children. Studies show that early childhood education has its greatest impact on the most vulnerable children as it allows them to be in a safe and reliable environment. However, in the current situation, the protective effects of schooling are being undermined by the economic and social crisis facing the country.

Amidst this unreliable and stressful situation, the dream of education as an equalizer is slowly turning into a nightmare. As children begin to respond to the double whammy of having to deal with stressful situations both at home and in school, a generation more unequal and more prone to conflict is likely to arise.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate