Dubai Expo 2020: a Perfect Platform for Maduro’s Propaganda

Since the 19th century, the Expos have been selling a specific view of technical progress. Now they sell autocracies such as chavismo and its allies, too

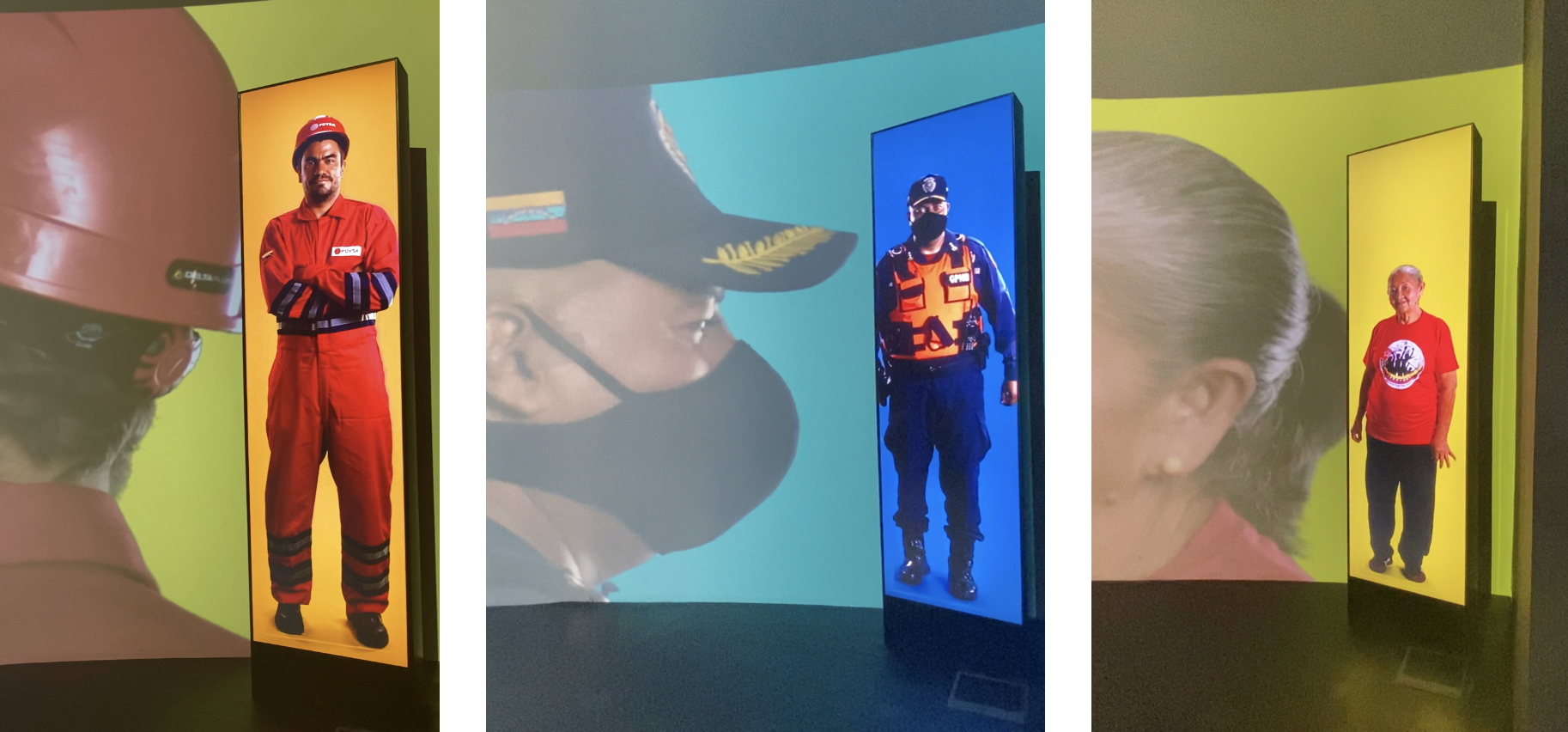

Photo: Pamela Martínez

I went to Expo 2020, currently taking place in Dubai, with caution.

The Expos are based on a linear timeline of progress that is simply faulty. In the mid-19th century, at the zenith of the British Industrial Revolution, Britain decided to hold ‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations’ to display industrial advances. Queen Victoria invited over ten European and American nations to take part in the exhibition in Hyde Park (London). As time passed, Expo developed into a space of technocentrism where countries with former colonies would pride themselves on their advancements. They started promoting an exchange of technology, trade, and culture among themselves but excluded their former colonies from this exchange while, paradoxically, having benefited from them.

I also knew it would be difficult for me to engage in a space that defends the compartmentalizing of the world and its peoples under the concept of a nation-state. As a student, I’ve learned that such a concept is violent to more people than we think, for it inherits colonial classifications which consequently exclude, fixate, and invisibilize communities. Moreover, it feels violent to think that there can be places where one is expected to suspend one’s disbelief towards government rhetoric.

In 1935, Walter Benjamin wrote in one of his essays that German fascism renders politics aesthetic. As I understand it, the aestheticization of politics is the act of performing political discourses as absolute truths. If such rhetorics are considered irrefutable then they become apolitical.

As I was walking Expo 2020 in Dubai, I felt uncomfortable knowing that so many people, histories, and ideas are excluded through ambiguity. For example, the mobility pavilion made strong statements about migration without explaining the historical causes of these geographical mobilities: “Global migration has risen by 57% since the year 2000. There are now over 272 million migrants living in new homes around the world.” The semantics of this phrase signifies that these migrations occurred naturally and happily, by choice. It assumes that every migrant indeed has a home. Are the forcibly displaced counted among those too?

The way we choose to interact with this space reflects our implicit—and sometimes racialized—assumptions of countries.

I spent two days at Expo observing how people would thoughtlessly pass by if pavilions weren’t glamorous or had groundbreaking architecture. It feels violent because the general aesthetics reproduced the inequality between the Global South and the hegemonic—economically speaking—countries. Bigger countries with more resources end up having greater visibility, and hence, more opportunities to assert their commitment to “progress” while smaller ones remain minorities within a globalized perspective as their voices remain in the margins, and this marginalization is asserted by the way Expo is curated. From a micro-political perspective, the process of representation goes through a series of approvals by each country’s “official” representatives and, ultimately, by the administration that curates Expo as a whole. These choices, determined by implicit rules, also promote a monolithic ‘national’ identity that excludes outliers of those ‘official’ discourses.

The aestheticism of the politics embodied within Expo allows the people in positions of power to represent a nation-state that reproduces discursive violence with real-life consequences. For example, the Indian pavilion perpetuates Hindu nationalism as an ideology, while violence against Indian Muslims increases. Or Expo privileging dictatorial regimes as they validate their official narrative. That was the case of the Venezuelan pavilion.

Vague On Purpose

At first sight you see a multicolored pavilion that vaguely seems to be influenced by Carlos Cruz Diez’s kinetic art. After you enter, the first thing you see is a plain salon with multiple screens on each side playing visual representations of Venezuelan citizens rotating on their own axis in front of monochromatic backgrounds, no context given. Among those you see a man with a tricolor hat and Chávez’s face and a text “Chávez somos todos” on the side, a man with a PDVSA red uniform, a GNB officer. Then there’s an attempt to portray vague representations of minorities and typically marginalized communities such as children, Indigenous people and women of color dancing at the carnival of El Callao. It mentions some Venezuelan athletes who recently won medals in Tokyo, despite many of them having to train abroad since the government doesn’t provide them with infrastructure nor resources that allow them to train professionally. As these unfolded, outrageous statements such as “Venezuela has a pension system for 100% of its senior citizens” appeared. My heart started racing when I saw their statistics on Venezuela’s current population. According to Maduro’s regime, there are around 33 million people in Venezuela and “Venezuela is a country open to migration. Immigrants make up 4% of the population” while completely denying the massive exodus of Venezuelans in recent years.

You walk a bit more and see pictures of happy children with messages like “school enrollment is 93%, 8 million children and adolescents” and “The average age of young population is 27 years old” without any specificity about what these numbers mean. Assuming that this statement is true, a foreigner might think that this number means our economy could be strong because our labor force is young. But to me, this depicts all the brain drain from our country, since those who are younger than 27 fled as soon as they could. Seemingly neutral statements such as “75% of the urban population is distributed among major cities on the northern coast” are violent because it seems that the regime prides itself in how centralized our country is towards the capital, while in reality, it’s the result of failed economic policies and urbanization, even before the chavismo. And still today, it’s even more violent because we know about the regular power cuts outside Caracas. Then they showcase arbitrary statements such as “Women are in charge in 40% of Venezuelan homes’.” Was this supposed to be some sort of declaration of gender equality?

You walk a bit more and see pictures of happy children with messages like “school enrollment is 93%, 8 million children and adolescents” and “The average age of young population is 27 years old” without any specificity about what these numbers mean. Assuming that this statement is true, a foreigner might think that this number means our economy could be strong because our labor force is young. But to me, this depicts all the brain drain from our country, since those who are younger than 27 fled as soon as they could. Seemingly neutral statements such as “75% of the urban population is distributed among major cities on the northern coast” are violent because it seems that the regime prides itself in how centralized our country is towards the capital, while in reality, it’s the result of failed economic policies and urbanization, even before the chavismo. And still today, it’s even more violent because we know about the regular power cuts outside Caracas. Then they showcase arbitrary statements such as “Women are in charge in 40% of Venezuelan homes’.” Was this supposed to be some sort of declaration of gender equality?

Towards the end, there were some sort of colored cubes meant to refer to Jesús Soto and Carlos Cruz Diez, as explained by the administration in the pavilion, with no explanation and no artistic coherence to them at all.

The Venezuelan pavilion isn’t only inaccurate but also mocks the daily hardships of those who live in Venezuela. It is, again, portraying a sexist, patriarchal, and banal state unable to recognize its flaws. Instead, it makes a mediocre pavilion ambiguous enough for foreigners to not understand, yet political enough to advance the international perception of Venezuela’s (inexistent) plural democracy. It capitalizes on Indigenous peoples’ identity by stating the number of communities and how Indigenous languages are recognized as official languages. The Maduro regime publicly prides itself of having a Ministry for Indigenous Communities while, in reality, the state massacres them; it celebrates Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A, the state-owned (and only) oil company that doesn’t provide Venezuelans with gasoline. While Venezuelans have normalized a lifestyle in which they spend a quarter of their month queuing to fill up their tanks. It chooses to portray the Guardia Nacional Bolivariana as the safe-keepers of our country while, in reality, they have the blood from activists, political prisoners, and protesters on their hands. The Venezuelan pavilion is incoherent, cheap propaganda.

Maybe it’s utopian to think that opportunities such as Expo, where so many billions of dollars were allocated, would at least create spaces of encounter to engage with each other in different ways. Where discourses of the grandiose would be left aside to prioritize more human interactions. Perhaps there would be an emphasis in creating opportunities for the youth, for rising artists and entrepreneurs. Minorities would be self-represented, rather than being exoticized to perpetuate a false narrative of inclusion. Ideally, we would use these spaces to pressure governments to engage in an ethical, truly sustainable future: one that is sensitive to human and even post-human understandings of care. And if that were the case, I’d also expect accountability from whoever participates because what hurts me the most about seeing the Venezuelan pavilion, is the lack of accountability towards the public. Expo becomes the platform of fake news and no one seems to know enough about how much of a distorted reality it is, and if they do, they don’t seem to care.

Expo isn’t an open space where you are allowed or invited to ask questions. Instead, you are expected to absorb the information (if there is any) and accept it as the absolute truth. Otherwise, suspend your disbelief if you disagree with it. What frustrates me the most is the act of self-censoring. It’s violent because it’s overly simplistic when attempting to represent the plurality of communities and lived experiences, within a nation. Thus, who is it for?

If we consider that most if not all pavilions are approved, if not fully funded, by their respective states, how can I happily visit the Belorrusian pavilion knowing a close friend was arbitrarily detained during the recent protests in 2020? How can I visit the Chinese pavilion knowing the ethnic genocide they are committing? How can I engage in Israel’s theme of transparency? How can I be entertained while some acquaintances are worried about their families in Sudan?

Perhaps, it’s only for the amused tourists taking photos of themselves or the investors walking around as they play a monopoly game. Expo isn’t for everyone and certainly not for me. I hope that it isn’t for you either. It’s exhausting. Ignorance becomes a blessing for those who can thoughtlessly engage in spaces such as this.

Even if you consider Expo interesting due to its artistic qualities from the point of view of its architecture, its performances, their VR technology, the performativity of each pavilion is the result of its politics and can’t be detached from it, so visit Expo and politicize it.

I don’t regret the knowledge I’ve acquired through academia, experiences, or really, through my own and my friends’ pain. But I grieve the literal and metaphorical freedom to express my political beliefs. Mostly, I grieve not being able to do something about it, even if it’s just screaming loudly in public.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate