An Overview of the Decline of Oil Production in Venezuela

Now that we left 2020 behind, we can see how oil production in “the country with the biggest reserves on Earth” has fallen during the Maduro years, according to OPEC

Photo: Reuters

We know Venezuela has been losing oil production capacity for years, due to mismanagement and corruption, and the Maduro regime has been unable to rebuild extraction and export because of a cluster of reasons where the international sanctions aren’t the only factor.

We also know that the current production is only comparable with the levels of almost a century ago, when Venezuela was just reaching better agreements with the international oil giants that were exploiting oil in the country, decades before the nationalization of those assets and the development of a proper native energy industry during PDVSA’s golden years in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

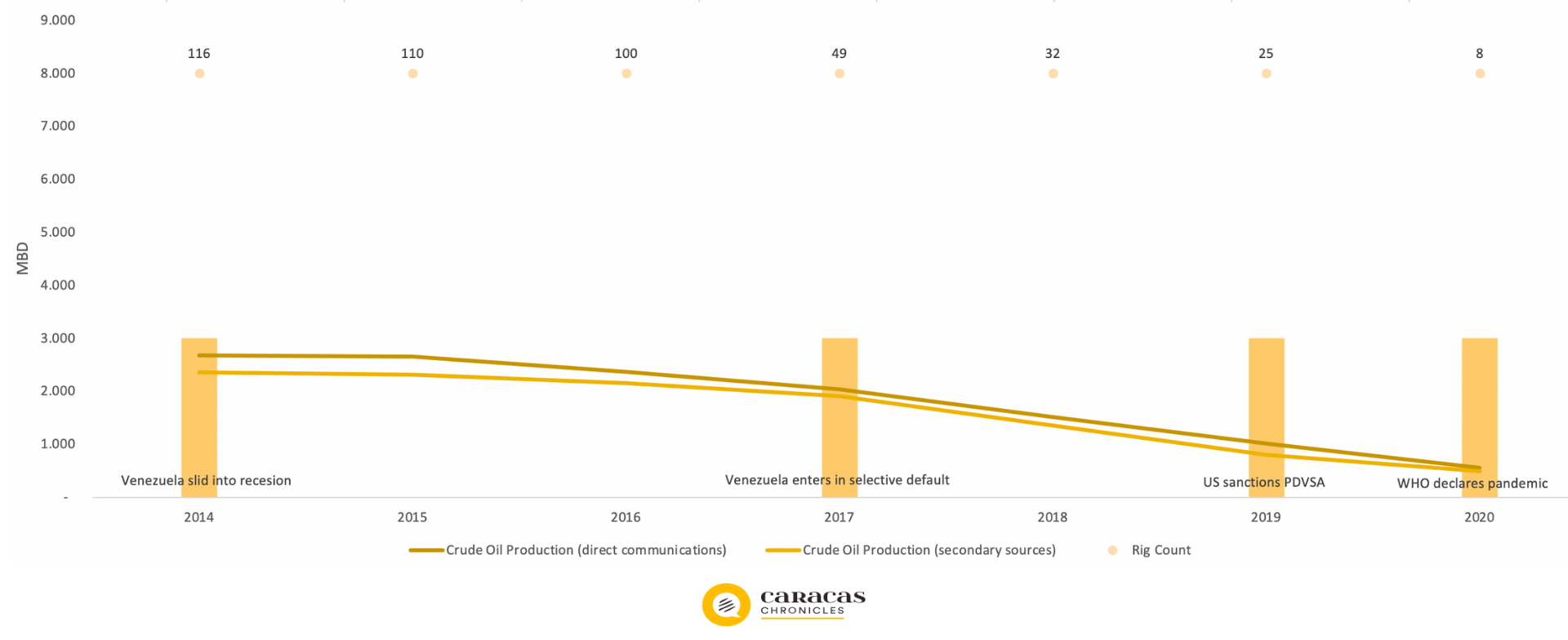

But the OPEC data allows us to see a clear picture of the drop—like a Sukhoi that lost its engines or a landslide in a tropical storm. Please consider that “direct communication” means the figures sent by PDVSA to OPEC, and “secondary sources” are the figures made by OPEC following other sources.

By 2014, Venezuela was producing almost three million barrels per day and had 116 active drills, the inertia of the bonanza that helped to reelect the ailing Chávez in 2012. But in 2017, when the economic crisis exploded and the country entered default territory (road to hyperinflation, massive shortages and mass migration), came the big fall… which preceded the sanctions against the Venezuelan State, effective since September 2019. When sanctions arrived, the number of active rigs had reduced to 25.

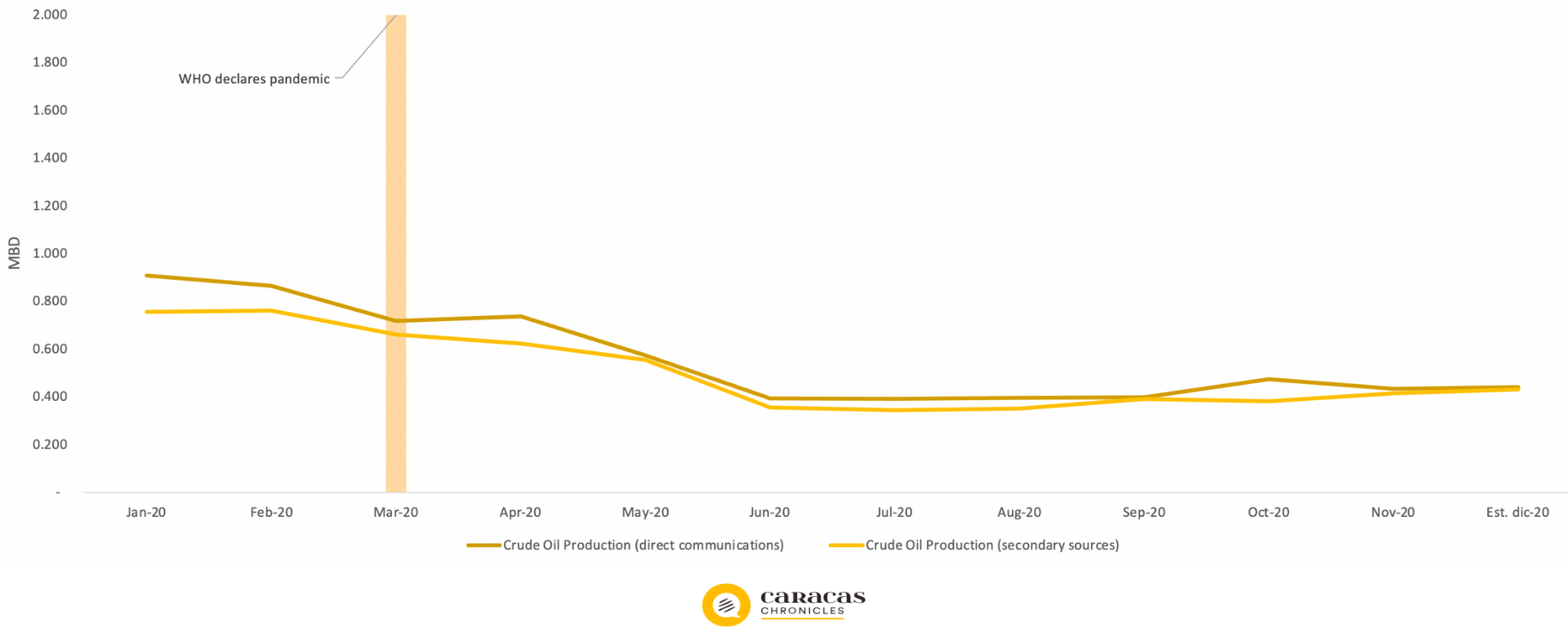

Looking closer at 2020, with the same data sources, what we see is the plateau that the Maduro regime is trying to describe now as the result of an imperialist siege, after blaming low prices on another imperial conspiracy. In 2020, the oil production couldn’t surpass a ceiling of about 800,000 barrels. Behind this is some impact of sanctions, of course, because they actually make it more difficult to import supplies and equipment to fix and refurbish refineries and plants, and sanctions have thrown the Venezuelan oil business deeper into the darkness of unchecked gray markets and mafia-like deals with Maduro’s international partners—two things that probably won’t be solved by lifting them. The trend since 2014 has been steady.

The rest was a combination of unsuccessful attempts to restart production because of the government’s very limited skilled labor and investment capacities, the lack of results from the Iranian and Russian cooperation, and the extent of the damage made by years of neglect on the national energy infrastructure. However, the year started with a bump in production and exports. The regime is promising—again—to increase production to over 800,000 daily barrels (Maduro has even spoken of 1,000,000) by the end of the year, but the truth is that in the current state of the industry they will hardly be able to break half of that.

We’ll have to wait and see if the “anti blockade” and the efforts to further involve their foreign allies through restructuring schemes produce results. For the moment, this is the picture of the situation, according to OPEC, not American media or independent news outlets.

For a better understanding of the energy sector in Venezuela, contact us here.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate