Why Venezuela Wants a Piece of Guyana

Maduro can try to resurrect an old claim to distract Venezuelans, but what’s the geographical reason to want the Esequibo? How would we benefit from it?

Photo: Things Guyana

Since the 19th century, Venezuela has claimed a good part of what is now the Republic of Guyana. Venezuelan kids were used to seeing that “zona en reclamación” as a striped area attached to our country’s Eastern border, and imagine it like the hind legs of a cow, a rhinoceros, or even an angry elephant, whose head lies between the Guajira and the Paraguana peninsula.

Decades pass and that area remains under Guyanan control. But the Esequibo, as that territory is known because of the river that marks the border that Venezuela claims, is still a subject revived every once in a while by different governments, when they’ve deemed it convenient.

2020 was going to be a crucial year in the century-old dispute, after the International Court of Justice claimed jurisdiction (in 2018) and was expected to give a final decision in March. Although the case was stalled by the pandemic, it’s still alive, and it has become a part Nicolás Maduro’s foreign enemy narrative.

The Esequibo dispute, however, isn’t just a topic to distract us; although the claim is usually approached from the historic perspective, it’s better to have a prospective vision too, from a geographical point of view, and even dare to think about which options a democratic Venezuela would have to manage a territory which, truly, has always been foreign to us.

What’s the Esequibo?

That area with black and white stripes you see on the eastern side of all Venezuelan maps (made in Venezuela), is actually a territory of 159,500 square kilometers currently in dispute between the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and the Co-operative Republic of Guyana. It’s adjacent to the southeastern Venezuelan border—from the Roraima to the southern Orinoco delta—, and on the western Guyana border and the Atlantic window between the mouths of the Orinoco and Esequibo rivers. The territory is home to around 300,000 people, between Afro-Guyanese (38% of the population), Indo-Guyanese (52%), and Native Indigenous people (Waraos, Arawaks, and Caribes, 10%).

The Esequibo is part of the Guiana Shield and just like the neighboring Venezuelan regions, it has a tropical climate, with a dry season from November to April, and a rainy season from May to October. It’s a bio-diverse natural context, on top of geological strata rich in minerals and hydrocarbons.

When did the dispute begin and who’s been involved?

The history of the current conflict goes back to the end of the 18th century, when the Dutch and Spanish were competing for the region. The Dutch, who at the time controlled Dutch Guiana (now the Republic of Suriname), handed over the territory of what is Guyana today to Great Britain, who had a better historical understanding—probably more than we did—of the geostrategic importance of the land, when they sent captains Walter Raleigh, Daniel O’Leary, and Robert Hermann Schomburgk to explore.

The possibility of establishing a Venezuelan Esequibo doesn’t depend on the factual and diplomatic tools, as much as it does on how Venezuelans and Esequibans understand and see themselves in each other.

Halfway through the 1830s, after the British envoys’ expeditions, interest in the area began to flourish to the point where, in 1840, they tried to move the Guyana border almost to the mouth of the Orinoco river. Bear in mind that Venezuela back then wasn’t very clear about its borders, nor did it have much control over them.

In 1899, an orphaned Venezuela trusted the United States with its diplomatic defense for the Paris arbitration. The court convened in Paris and was made up of two United States Supreme Court Justices, two assigned by the United Kingdom, and presided by Russian internationalist Federico Martens, and the ruling was in favor of Great Britain. But in 1962, Venezuela presented evidence of fraud, collected for at least two decades, to the UN, which suggested that Martens proceeded in a partialized manner.

In 1966, after Guyana got its independence from Great Britain, the Geneva Agreement was signed, a document where, in broad strokes, Great Britain recognized Venezuela’s claim over the territory, with the consent of the newborn Republic of Guyana, which would become part of the agreement. The 1899 Arbitral Award was replaced by the Geneva Agreement and is what stands today.

What would be the implications of annexing the Esequibo to Venezuela?

The list of natural resources we could gain includes an extensive hydrographic network that includes the Esequibo River and its Atlantic delta, the Cuyuní, Rupununi, Mazaruni, and Supenaam rivers, as well as the Potaro river and its 220 m Kaietem falls. Venezuela would secure an area with at least four different natural environments, with an altitude ranging from 0 to 1,500 m above sea level, including the Pakaraima mountain range, the Rupununi savannah, and the Canacu mountains. It also includes a variety of rainforests, flooding and coastal flatlands, and littoral forests. But probably the most attractive feature from this natural stock would be the bauxite, diamond, manganese, gold, uranium, oil, and natural gas reserves.

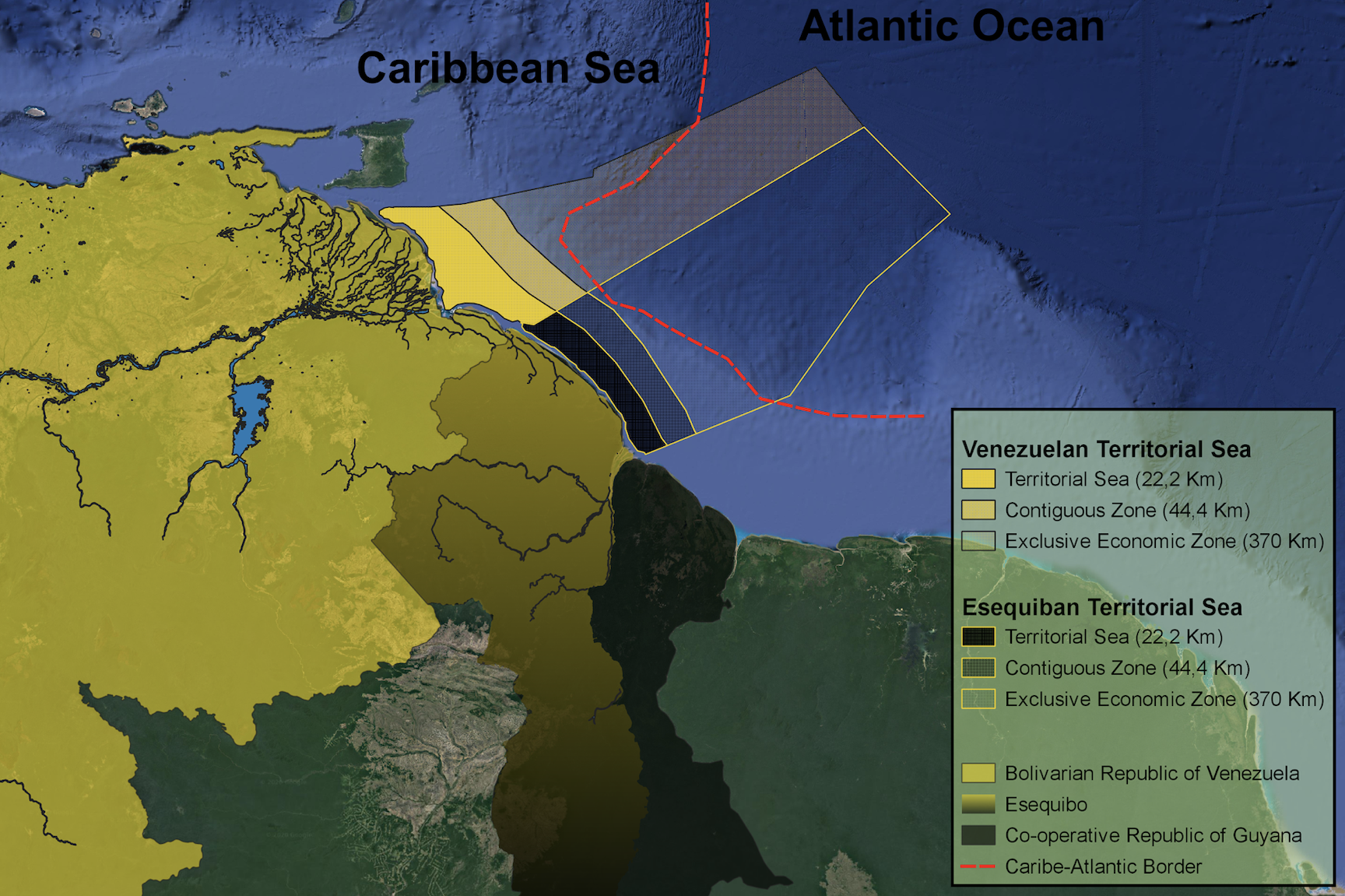

The northern coast of the Esequibo would give Venezuela a much more consolidated exit to the Atlantic ocean: our territory would gain 280 km of coast line, which would mean an expansion not only of its continental platform, but also of its sea limits, its adjoining areas and exclusive economic areas as well. This would generate total maritime sovereignty over the Atlantic for 22.2 km, and customs jurisdiction for 44.4 km. Venezuela now has the ability to cover the southern Caribbean thanks to the checkpoints at the Isla de Aves and the Los Monjes archipelago; if the coastal band towards the Esequibo is expanded, the fishing resources would be much broader, also strengthening Venezuela in terms of security and defense.

Which sectors of the Venezuelan economy would benefit from the Esequibo annexation?

As you can see on this map, the Esequibo would give Venezuela more than 400 km of sovereignty over Atlantic waters.

Photo: Reybert Carrillo

The Esequibo is already being exploited by the mining industry in Guyana and attracting international investment. The discovery of new oil deposits by Exxon Mobil in its territorial waters has sprung a debate where it places Guyana as the next oil boom in the western hemisphere, since it is estimated that the new deposits may contain around one billion oil barrels. Only transnational companies would be capable of extracting and refining it: Guyana is, in a sense, like Venezuela was a century ago. Those reserves are located in waters still in dispute.

In a responsible Venezuela, you’d have to think beyond extractions, especially when we know how the chavista Mining Arc project is destroying the Venezuelan Guayana, while a gold fever causes extensive damage in the rest of the country. If the Esequibo becomes Venezuelan, it could serve to increase the electric output through its rivers, and those basins, as well as the increased sea limits, giving the country more areas for fishing. Having almost 300 km of new coastland and over 40 km of ocean waters would benefit customs taxes by maritime transit, fishing activity, military exercises, international security and defense, tourist activity, strengthening commercial exchange with Europe and Africa, scientific development in terms of the study of delta mangroves in the mouth of the river, among other benefits.

Tourism would greatly benefit, too; the ecological diversity of the Venezuelan side of the Guiana Shield, would then expand to the Esequibo, including iconic landmarks like the Maringma and Ayanganna tepuyes in the Pakaraima mountains or the Camoa, Canucu, and Merume sierras. Venezuela expanding its jurisdiction over the shield would be argument enough to establish new measures to boost tourism and, at the same time, protect ecosystems that could give wider support to the diverse Venezuelan nature.

But how plausible is the recovery of the Esequibo?

When someone in Suriname thinks of a foreign destination, their eyes automatically focus on Amsterdam, not Rio de Janeiro or Montevideo—because even if they’re in Paramaribo, their concept of the outside world is mostly in Europe, not South America. The same thing probably happens for those born in Esequibo, who are more drawn to Georgetown or London than they are to Caracas. The possibility of establishing a Venezuelan Esequibo doesn’t depend on the factual and diplomatic tools, as much as it does on how Venezuelans and Esequibans understand and see themselves in each other.

The chances of Venezuela making a successful claim are blurry. This topic has been traditionally handled by politicians to improve their popularity, from the military invasion threats made by dictator Pérez Jiménez, to Chávez’s quest for favors in Georgetown. The case is currently in a total limbo, since none of the representatives of the Venezuelan Executive Branch (neither of them) have been convincing in defending a territory that’s ours and will probably end up lost in a pile of papers at The Hague.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate