Don’t Expect Many Changes from the Biden Administration

Trump’s Democrat successor took office last week. Carlos Romero reviews U.S.-Venezuela relations before we evaluate the present situation

Photo: Reuters

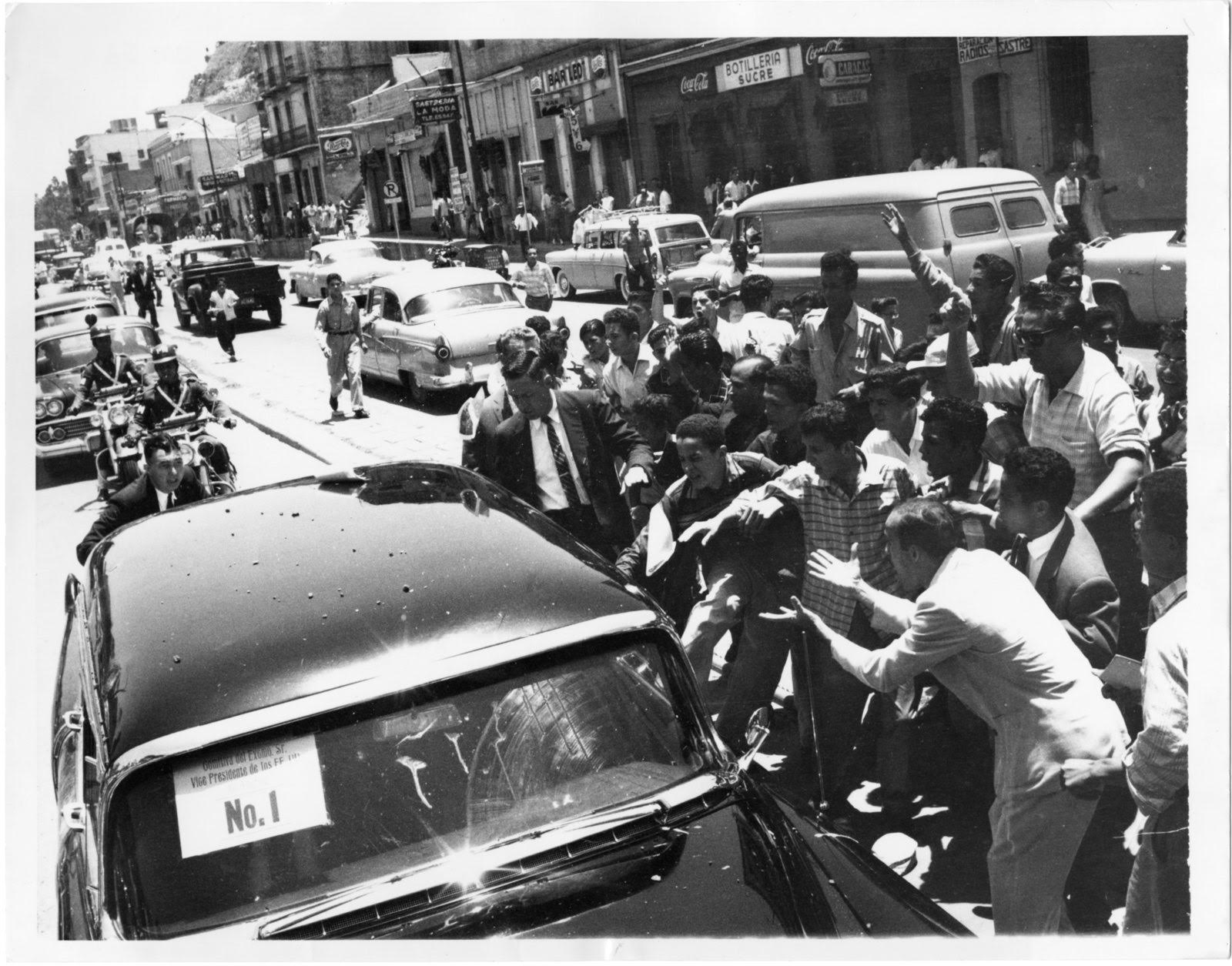

It’s 1958 and there’s a crowd outside the Maiquetía international airport in Venezuela, to reject Vice President Nixon’s visit. Insults, spit, eggs and rocks are thrown at him upon arrival in Caracas.

It’s 1961 and President John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jackie, are doing an official visit. Venezuela has been in a three-year period of democratic stability under Rómulo Betancourt, who’s hosting the couple.

It’s 1978. Jimmy Carter visits and is received by President Carlos Andrés Pérez. Oil prices and the drop of the dollar price brought the American leader personally to the nation.

Fast forward to 1990. President George Bush’s visit ends with 14 injured and 40 people arrested. The American president was visiting to promote a free-trade area in the region.

And in 1997, Bill and Hillary Clinton arrived in Caracas. They’re greeted by President Rafael Caldera and, in his first statement in Venezuelan soil, Clinton highlights the historical friendship between both countries.

The century was ending and, with it, the era of good relations between Venezuela and the U.S., an era marked in our country more by harmony than by conflicts. It was a relationship that stood amid a convoluted Latin America where authoritarianism was common and even though there were disagreements, they never harmed a friendship that started in 1834, with President Andrew Jackson recognizing Venezuelan independence.

Nixon in Caracas: the then vice president experienced first-hand the hostility of the left towards Washington

Photo: National Archives

Carlos Romero, a Political Science doctor and retired professor from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, thinks those times ended with Hugo Chávez’s arrival to the presidency, in 1999: “From the start, Hugo Chávez had the concise goal of reducing the relationship with the U.S., an important change because we came from a historical, fluid bond.” Now, in 2021, with a new man arriving at the White House, many are asking what will happen with Venezuela. Romero clears it up.

The U.S. generates passion and mistrust all around the world and now that polarization seems always present in Venezuela.

From the get-go, Chávez’s government limited the possibilities of a good relationship with the U.S., with his notions of a socialist revolution, the relationship with Cuba, the transformation of Caracas into a worldwide leftist hub, and his own relevance as a regional leader, meaning a situation described by an ambassador as the “wait and see” policy: There was an expectation on how radical would the Venezuelan government be and how that would affect the bilateral relationship. Wait and see became suspicious minds, particularly with the role the American government played in the 2002 Venezuelan coup, supporting Pedro Carmona when he took power. Then the oil crisis comes and Chávez gets closer to China and Russia, adding to a deep relationship with Cuba, making Venezuela more distant from America. From suspicious minds we went to do the right thing, a warning that Venezuela was taking a less than desirable road. Now, we’re in a phase that started with Maduro, what I call wait it out, because to the U.S., there has to be a regime change in Venezuela. This has deeply hurt the relationship between both countries. I’m interested in how there’s a sort of hope in the Venezuelan government for an improvement of the general situation with Joe Biden, after blaming Trump for policies that really began with Barack Obama. The U.S. is interested in fully supporting Juan Guaidó’s caretaker government, CITGO sanctions and freezing Venezuelan government’s bank accounts. Washington also leads the alliance against Venezuela in the entire Western Hemisphere.

Kennedy in Miraflores: Betancourt government knew how to handle friendship on their own terms

Photo: Francisco Edmundo Gordo Pérez

So, the relationship with Venezuela was always cordial until Chávez’s government?

They were always cordial, with moments of differences. In 1958, the Wolfgang Larrazábal era, dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez had just been overthrown, and the welcoming ceremony for Vice President Nixon was a very difficult situation. Later, during Rómulo Betancourt’s government, the U.S. didn’t support the “Betancourt Doctrine”, which was a refusal to recognize dictatorships that followed overthrowing of democracies. During Raúl Leoni’s government—despite the existence of a good relationship with the U.S. in the fight against Cuban influence, not only in Venezuela but also in the Caribbean—Venezuela opposed the American invasion of the Dominican Republic. There were economic differences during the first term of President Rafael Caldera, and also during Carlos Andrés Pérez’s first term. All through these years, there was the idea floating around of a catastrophe in the U.S. regarding oil supply if there was a breakdown in the relationship with Venezuela, but that’s just not the case anymore. Other suppliers have appeared, and Venezuela had to change its market. Remember that direct flights between both countries are forbidden, too. Venezuelan immigration to the U.S. is a lot more difficult now than it was 50 years ago.

Except for Nixon and Bush Sr., no Republican presidents have visited the country. Has the relationship been more tense when there’s a Republican in office? It seems there are more similarities with Democrats.

Undoubtedly. Venezuelan governments of the democratic era were closer to the Democratic party. In fact, there were some American politicians who had friendships with Venezuelan politicians, as was the case with Hubert Humphrey. There was a close friendship between Rómulo Betancourt and John F. Kennedy, as there was between Richard Nixon and Rafael Caldera, but we can’t say that all Republicans didn’t get along with Venezuelan leaders, either.

It’s not only with Venezuela; Donald Trump is considered one of the presidents to pay the least attention to the region. He only visited Buenos Aires in 2018. Other than that, he only referred to specific cases, on Twitter.

It was a negative agenda. Latin Americans didn’t take his obsession for building the wall with Mexico very well, and he didn’t encourage relationships in the hemisphere, just negative alliances against Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. He wanted to turn the OAS into a sort of “ministry for the colonies,” as the Cubans called it. He destroyed Latin American trade efforts over regional economic integration. Undoubtedly, Trump’s position divided the Latin American community, and Trump didn’t make any efforts to promote American investments in our continent. Trade was difficult, and there was a strong protectionism of the American economy.

Will the change of party in the American government influence the relationship with Venezuela?

We can’t expect many changes from Biden regarding Latin America or Venezuela; the U.S. has always been driven by national interest, and that’s a policy supported by the Democratic party, as we see it in Congress. The domestic problems that Biden is inheriting are too big and too many, so he won’t put the relationships with the hemisphere first. We have to wait for better conditions first.

Carlos Andrés Pérez and Jimmy Carter.

Photo: Actualy

And in the past?

It also had less influence than people think. I remember that when Nixon was president, he was adamant about the Chilean situation and that carried on to Gerald Ford, but Jimmy Carter introduced change, a more protective policy for democracy and human rights in Latin America. Then, with Ronald Reagan, it was all about geopolitics again. As you pointed out, the geopolitical issue is a lot closer to Republicans than to Democrats, who emphasize more the defense of democracy and human rights.

Something that remained constant was the policy towards Cuba, at least until Barack Obama’s presidency.

Yes, Obama changed the Cuban topic, he re-established diplomatic relations that had been broken in 1961, and applied measures that considerably reduced the embargo, which Trump changed again, the rollback. Trump cut tourism, cruise ships, remittances, and commerce between both countries.

Venezuela isn’t a priority for Biden, but how do you see the diplomatic relationship between both nations in the future?

At this stage, because I’m no Nostradamus, I can only say that I wish there was a more harmonious and more peaceful climate among Venezuela and the U.S.; the relationship came to a limit and there has to be a space for negotiation to stabilize them. The thing is, there are many people in Venezuela who aren’t interested in stabilization. Some opposition actors even went as far as to play the card of an alleged intervention by Trump.

Would you say that the diplomatic relationship with the U.S. has been beneficial for Venezuela? Or has it done more damage than good?

Of course it has benefited Venezuela. There are cases of leftist, proggressive governments that have had great relationships with the U.S.; I don’t understand why Chávez’s government, and especially Maduro’s, were so insistent in limiting that dynamic. We have cases in history that prove there can be a fluid, symbiotic relationship, considering the fundamental role of the U.S. is in the Western Hemisphere.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate