The Living Portrait of a Dying Town

In Once Upon a Time in Venezuela, Venezuelan filmmaker Anabel Rodríguez Ríos shows the lives of the people affected by the gradual disappearance of Congo Mirador, a water town in Zulia state

Photo: John Marquez

In 2009, Anabel Rodríguez Ríos was on location in Zulia, shooting a documentary about the unique natural phenomenon of the Catatumbo lightning. She and her team were staying in Ologá, a water town on the Maracaibo Lake, when some children arrived in makeshift boats made out of plastic fuel drums cut in half.

The kids came from Congo Mirador, a nearby town of houses built atop of pillars in the water (palafitos, as they’re locally known). Anabel was so intrigued by how these children would grow with their hands that she made a short film about them: El barril (2013), as part of the Why Poverty series. El barril shows the precariousness of the children’s lives, and how they play in the same waters they use to relieve themselves.

“This isn’t just a film, this is practically a life’s mission,” Anabel says from Vienna, Austria, where she’s lived since 2012 and from where she’s promoting her work. “What we want is to show the world what’s going on in Venezuela.”

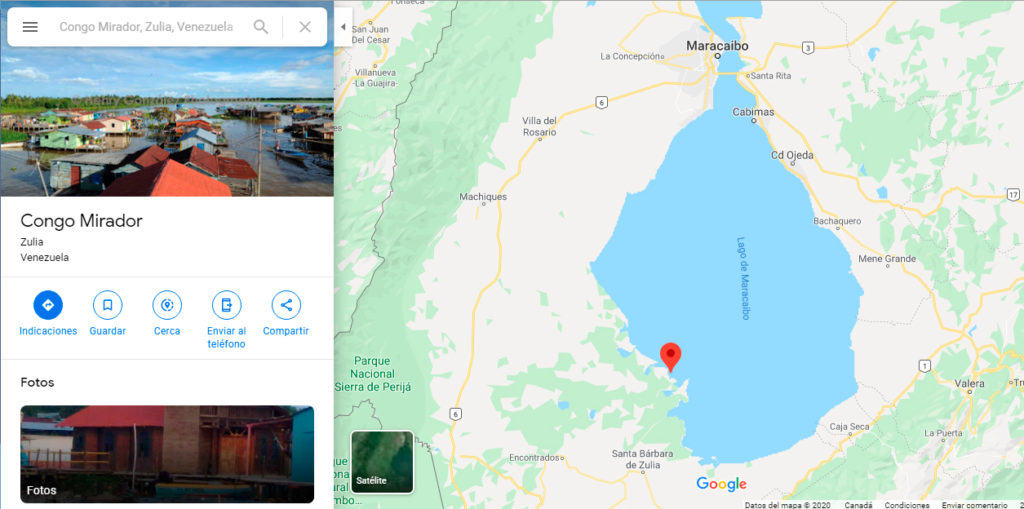

This is the location of Congo Mirador, near the old routes by which the products of Zulia went abroad, via the rivers and the Lake.

Photo: Google Maps

But there was more to the story about Congo Mirador:

“At a glance, it’s a town just like many in Venezuela. However, as an icon, it’s wonderful. It recalls the origin of Venezuela’s name: little Venice.”

This fascination led to the idea of a feature-length documentary about the town, a treatment only three pages long (one for the project, one for budget, and one for the team) that The Tribeca Film Institute, an American foundation supporting independent films since 2002, approved for financial support.

The filmmakers spent five years of production, making visits three or four times a year, in which they outlined parallel plots. One of them was the deep political polarization during the campaign for the parliamentary elections of December 6th, 2015, where the opposition beat Nicolás Maduro’s regime.

The documentary, Once Upon a Time in Venezuela, was released in 2020, produced by Brazil, the United Kingdom, and Austria, and supported by the Centro Nacional Autónomo de Cinematografía de Venezuela, Ibermedia, IDFA Europe and IDFA Bertha Found, both programs from the Amsterdam Documentary Institute.

The viewer can appreciate the day to day life of Congo Mirador as a sort of reality show, respectful of protagonists who show an unlikely normalcy in the midst of spiralling decay.

In 99 minutes, it narrates in an intimate and chronological way, the last five years of a town that’s over 200 years old. The viewer can appreciate the day to day life of Congo Mirador as a sort of reality show, respectful of protagonists who show an unlikely normalcy in the midst of spiraling decay: the town is vanishing with the ground sedimentation, the oil pollution, and plain abandonment from the national government.

Lightning, Cabrujas and Gallegos

Anabel graduated from Universidad Católica Andrés Bello’s School of Journalism and won a scholarship from the Fundación Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho that she used for a Master’s Degree in Directing at the London Film School. There, she shared classes with Sepp Brudermann, producer and writer for the documentary who, besides being her ex-husband and father of their son, is an “honorific” Venezuelan, as she calls him, because of his love for the country.

Anabel links the history of Congo Mirador to a phrase by Venezuelan author José Ignacio Cabrujas, who wrote in an essay that Venezuela is like a hotel, where people come, get the best out of the place and then leave.

But she also sees the ideas of Rómulo Gallegos:

“Doña Bárbara exists and her name is Tamara Villasmil.”

Natalie, the teacher from Congo Mirador, has a duel with the Chavista chieftain in the film

Photo: Once upon a time in Venezuela

She means the local government leader, representative of the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela, devout Hugo Chávez follower and the person with the best living standard all around. Confrontations between her and Natalie, a teacher from the only school in town, show on a small scale the extremes of polarization in economic, political, and social terms in the country. The audience will find that each of these women aims to help, in their own way and from their standpoint, with Congo Mirador’s survival.

Let It Be Known

The documentary opened the Sundance World Documentary in January of 2020, and it has since been presented at the Miami International Film Festival, selected for the Cartagena Festival, Hot Docs in Toronto, and at least seven other international festivals—USA, Mexico, Málaga, and Canada again, at the VIFF Festival in Vancouver, have been the stage, along with other Latin American countries.

And while its story comes to life across the world, there were only about nine families left in Congo Mirador in early 2020.

In September, it was recognized as Best Documentary and received the Press Award at the 16th Venezuelan Film Festival.

And while its story comes to life across the world, there were only about nine families left in Congo Mirador in early 2020. The depth of its waters is less than a meter high, and most of its buildings have collapsed or are unusable. All of this because of the sedimentation process which, since the start of the ‘90s, adds more and more mud to the place’s foundations.

Up until 2013, Congo Mirador was a town made up of palafitos with a population of around a thousand people. They lived mostly from fishing and tourism, with its privileged location to watch the Catatumbo lightning. Now, people are leaving with everything packed, even their homes—yes, the whole house balanced between two boats, headed to Ologá or other neighboring towns.

These towns were part of an agricultural economy with foreign trade that was disappearing

Photo: Once upon a time in Venezuela

“We’re not left-wing or right-wing,” says Anabel, “we’re humanists looking for the audience to empathize with these people who are going through a rough situation. People are literally drowning, so they leave.”

For the filmmakers, the pandemic meant a break in the festival circuit:

“We were lucky that the film premiered and it’s out there. We have mixed feelings because for a documentary, the first six months are basic in terms of exposure and this changed with the COVID-19 dynamic. So, we’ve had to change the strategy, as all independent filmmakers have.”

But in spite of these obstacles, the film keeps on traveling around the world online, with the “new normal” of COVID-19 that festival organizers have adopted.

The effort made by Anabel and her team is manifested at length in the film. Silences are protagonists and carry their own rhythm, encompassed by strong and colorful photography.

While the filmmaker sees the history of Congo Mirador as a small blood sample showing the health of all of Venezuela, she also insists on the evolution of the town as a patient. Today the blood test is bad, but after better treatment, another test will show good values on a literal rise.

“I hope that the country doesn’t stay behind in a wasteland because I do believe there’s hope, there are people fighting hard. May we rise like a phoenix; it’ll be hard, but Venezuela won’t just stay down.”

To watch the film and support its Academy Awards campaign, go here. Once Upon a Time in Venezuela is also available on Cine Mestizo.

A Spanish version of this piece was originally published in Cinco8.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate