Forced Disappearances: The Other Tragedy From 1999

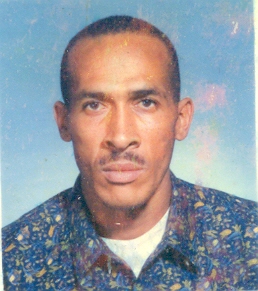

Oscar José Blanco Romero wasn’t dragged away by the river or the sea. His case is one of the four emblematic forced disappearances of the Vargas tragedy, the first disappearances of the chavista government

To Alejandra, "the person who dies is the one you bury."

Photo: Guillermo Suárez for Cofavic

“Let me tell you the story,” says his wife, Alejandra Iriarte de Blanco, 21 years later.

It was on December 21st, 1999, five days after the National Constituent Assembly (that year Venezuelans approved a new Constitution on December 15th) decreed the state of alarm in the Federal District and in other eight states of Venezuela. The flood made the mountain melt into the sea and the mudslides covered two thirds of Vargas state. Thousands died, and many thousands more lost their homes. The sun was out, and the Blanco family was thankful because the house that Oscar built was scratchless.

Around 2:30 p.m., Alejandra, her children Aleoscar (12) and Oscar (7), and nephews Edwar (6) and Orailis (2) crossed the street to hang the freshly laundered clothes to dry. Oscar stayed home with his mother-in-law when a terrifying sound petrified them: it was the sound of a different kind of tragedy, a rain of bullets. Around 20 men from the Batallón de Infantería Paracaidista Coronel Antonio Nicolás Briceño announced their arrival. Tragedy snuck in the Valle del Pino slum of the Los Corales sector, in Caraballeda, Vargas state.

Alejandra ran home, four children behind her. The Army arrived first and blocked their entry. At least five officers entered the house looking for money, drugs, weapons and stolen objects. It was part of a special operation to bring order back to the area, where crime was more devastating than the rain. Officers complied with the orders of Lieutenant Federico Ventura: “Wreck the whole thing!”

Oscar was part of that “whole thing.”

He was beaten in front of his wife, kids, mother-in-law and everyone else in the slum. The more they hit him, the more his children cried; “Tell them to shut up!” ordered the lieutenant. They destroyed everything with the same rage the river carried, like the mutiny was in the walls they had just painted, in the leftover bollitos de jurel, or in the branches of the Christmas tree..

Around 5:30 p.m., without a crime and without a warrant, the battalion handed Oscar over to six other armed men in gray uniforms: officers from the National Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services, the dreaded DISIP, this time led by “commissar Roberto,” acting under orders of Lt. Col. Francisco Briceño.

They took Oscar, a Venezuelan citizen from the small town of Chuspa, 37 years old, husband, father, handyman, home appliance repairman, pork salesman, a man who provided three daily meals for his family. Tall, athletic, with brown skin. He was wearing shorts and a white t-shirt. His presumption of innocence was also snatched that day.

The officers didn’t record anything because they were in a hurry. They just told Alejandra: “We might let him go shortly. We’re not keeping anyone detained.” She believed them.

“The thing I remember the most about that moment when he was taken in handcuffs down the stairs of our slum: the way he looked at me was different,” says Alejandra. Oscar warned: “Negra, pendiente.”

She’s been pendiente ever since.

The Search for Oscar

Oscar didn’t return on December 22nd. Alejandra started looking for him on the 23rd. She asked around, close to home at first, and then farther and farther away. That’s how she made it to the 58th Garrison of the Guardia Nacional. Oscar’s name wasn’t in the official list of people detained, but they told her that the DISIP (the Venezuelan intelligence police, which eventually became SEBIN) camp at the Caraballeda golf court had him. There she was told the detainees were at the Maiquetía International Airport.

Alejandra had to tie a rope around her body to cross the overgrown river in Caraballeda. She would have drowned if it weren’t for someone pulling her to the surface with a stick. Oscar, however, wasn’t at the airport:

“I was told that they were at the Helicoide prison, but one man asked for his name. I said ‘Oscar Blanco’ and he stared at me, laughed and said nothing else.”

Oscar is dead. There are many DISIP officers that tell stories to each other. Where he is, they haven’t told that particular story yet, but all those people who were taken from their homes were killed.

Alejandra didn’t only cross the river; she walked over filth, fallen trees and debris. She looked carefully at every dead man she found, in case it was hers. When coming across dead dogs, she’d close her eyes and keep on walking, avoiding the blood from bodies that burst open inside their homes.

The only buses traveling to Caracas were in Maiquetía, far from her.

“My feet cracked because of all the sand, water and the walking. I made it to the Parque del Oeste, in Caracas, going then to the Helicoide and ‘Oh, no, he’s not here,’” Alejandra says.

The following weeks, Alejandra left every day at 6:00 a.m. and returned home after 11:00 p.m. She always carried candles, to light the way back and light hope. She continued searching wherever they told her. “They were killed over there” or “they were dropped over here,” or “they’re tied up around Naiguatá and they have them working on the road there.”

“We went everywhere, yelling, whistling and nothing. It was just rumors,” she says.

She searched for him in all places, abandoned or ruined by the floods, places that could have been perfect for clandestine detentions or executions. She looked for him in her dreams and nightmares. She searched like the State didn’t, because they only sent the occasional prosecutor to collect the same testimony, handwritten by Alejandra.

So Oscar’s cousin told her to go to “a witch who knows a lot.”

“I’m a Catholic, I don’t believe in that, but we went, all hush-hush. I was desperate. She grabbed a pencil and a piece of paper, and went: ‘I’m going to spin it. If the pencil stops, he’s dead.’ Said and done. She said he was killed that same day and that he would never be back.

Alejandra didn’t believe her. In January of 2000, human rights NGO Cofavic arrived at her home and accompanied her to the only place where she hadn’t looked: the Bello Monte morgue. To her relief and anguish, Oscar wasn’t there either.

With Cofavic, Alejandra learned everything that nobody had explained before: Oscar wasn’t just taken. It was an arbitrary detention, a forced disappearance and a human rights violation. So, Alejandra, Oscar and their children were still being denied protection, the rights and guarantees that come from their mere existence meant nothing.

The Blanco family tragedy became a national and international calamity.

The scene at Los Corales, in Vargas state, showed the full effect of the flood.

Venezuelan Justice: Another Search

In January of 2000, Cofavic requested Oscar’s habeas corpus to the 5th Criminal Court of Vargas State. General Lucas Rincón, general commander of the Army back then, admitted that Oscar was detained by members of the battalion and was handed over to DISIP officers.

But mere days later, in February, Captain Eliécer Otaiza, DISIP director, reported that Oscar’s detention wasn’t in their files or ledgers. That same month, a court said that the habeas corpus didn’t proceed because there was nothing that the court could rule on; Oscar wasn’t detained, legally or illegally, according to the authorities.

In May 2001, General Prosecutor Isaías Rodríguez submitted a special request to revise the decision and the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice ruled that it didn’t proceed, because the habeas corpus wasn’t the correct instrument to find Oscar.

It was suitable, fair and necessary. According to what Alejandra said to journalist Maye Primera in 2011, Hugo Chávez told her and Gisela, Oscar’s mother: “I promise I will work for justice. Not only so your loved ones appear, wherever they are, but also to find the people responsible for this.” That was on January, 23rd, 2000, in the presidential visit to the home of Roberto Hernández Paz, one of the other four forced disappearances.

Between 2001 and 2018, there were first instance court decisions,two by the TSJ Criminal Chamber, and two by the Constitutional Chamber issued two more. Two of the people charged were released: sub-commissar Casimiro Yanes and general commissar Justiniano Martínez, in charge of all DISIP operations carried out during the tragedy. Few achievements, that toppled soon after. Too many obstacles. Impunity.

“At some point, a prosecutor told me: ‘Oscar is dead. There are many DISIP officers that tell stories to each other. Where he is, they haven’t told that particular story yet, but all those people who were taken from their homes were killed.’ I always see in my mind that he’ll appear one day, because those prosecutors pretend they’re you friends, and they’re not. To me, the person who dies is the one you bury,” says Alejandra.

So while the case continued in court, Alejandra kept searching. She was told that Oscar was a prisoner at Tocorón, that he was a prison leader there: “I went to Tocorón, I think it was on a Sunday. I saw the prison leader and he wasn’t Oscar, but I didn’t waste my time further. I wasted my time many times when I went to court.”

International Justice: the Only Finding

After the habeas corpus in March of 2000, Cofavic denounced Oscar’s disappearance before the Secretariat of the IACHR and, in July of 2004, the commission introduced a lawsuit against the Venezuelan State. The case of Romero Blanco and Others vs. Venezuela was the third Venezuelan case to go to that court and its resolution only took 16 months. In a public hearing, in June of 2005, the State said it would collaborate in good faith with the suit and accepted its international responsibility to offer an amicable solution to the victims and to the Court. In November of 2005, the Court issued the sentence: “The Court has established that after six years, impunity regarding the events of this case prevails.” International justice said what the Venezuelan justice still doesn’t, to this day: Oscar’s right to life, personal integrity, personal freedom and judicial guarantees were violated by the State.

Oscar Blanco, victim of a violence that became too common in Venezuela.

International agreements established in the Inter American Convention about Forced Disappearances and in the Inter American Convention to Prevent and Sanction Torture were also violated. Because of the isolation and the secrecy, Oscar could have been beaten many times after his arrest.

“What happened after that?” says Alejandra, “I was making a bank deposit when I saw a DISIP car pulling over. Then I saw this guy, Casimiro Yanes. He should’ve been in jail. Imagine how scared I was. I then saw him one day at the airport too.”

Invisible Reparations

Alejandra fixed and repaired what she could after Oscar’s disappearance.

“So many things that the house needed and nobody to do them… They left nothing, they broke and damaged everything they could. I missed him. My four kids and I, we slept in the same room, in two beds, because I decided so. I was afraid to leave them alone and have them taken.”

Oscar was also needed outside the home. He was missed when Alejandra started selling soup, sodas and beers to the homeless who started returning from the shelters after the flood. He was missed when they had to sell empanadas and juice on the beach. He was missed when Alejandra rented, bought and sold a hot dog truck, when she ran a lotto agency and even now it’s a shame he can’t see the new truck where she makes burgers.

Alejandra, Gisela, Aleoscar, Oscar, Edwar and Orailis repaired their lives how they could, and without the reparation that the State still owes them, as the IACHR ruled: $280,333.33.

International justice said what the Venezuelan justice still doesn’t, to this day: Oscar’s right to life, personal integrity, personal freedom and judicial guarantees were violated by the State.

“I never waited for it. I knew it wasn’t going to happen. While this government is in power, it won’t happen. That ruling happened in 2005, they had a year to pay and it’s been 15… You think they’re going to do it now if they didn’t do it back then?”

The IACHR ruling is, in itself, part of the reparation necessary to the Blanco family. But so many other reparations are needed, for Venezuela too.

The Constitution of 1999 was violated six days after it was approved: it established forced disappearances as a crime. Now, 21 years later, reforms are still vague about their punishment, and the law hasn’t been changed to make habeas corpus a more efficient resource, compatible with the Human Rights Charter.

In 2009, the DISIP became SEBIN, and the excessive use of force that started in 1999 became a systematic pattern through all security forces. They coordinated and perfected crimes instead of preventing them. 2014, 2017, and 2020 came with reports of crimes against humanity in Venezuela: one by the UN Fact-Finding Mission and another by the ICC. All those reparation measures that could transform the country are missing, like Oscar.

“See? There’s no justice, no reparation. Nothing. Six or seven years ago, I started making peace with the fact that he might be dead because he would be home otherwise. You know I’ve looked everywhere, and it’s true: some people go missing and go crazy. If he shows up, he’ll be welcome… but it’s been 21 years.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate