Venezuelans Stuck Abroad Fight on Their Own to Come Back

Thousands of Venezuelans are stuck outside of their home country. Unlike the dire situation of migrants coming back home, Venezuelan travelers are invisible to the support of governments, and have had to organize to re-enter the country

Two Venezuelan governments, and none that can actually help.

Photo: Sofia Jaimes Barreto

To reach the closest thing to a notion of home, Angel* had to get married.

“Every morning that we spent stuck in Panama,” he says, “we woke up wondering how something that we had planned so, could have ended this royally ruined.”

Angel speaks with a slight Spanish accent (his second nationality), and a thick, palpable despise against the Maduro regime that he blames for the five months he spent stranded outside of Venezuela when the COVID-19 pandemic provoked the closing of borders everywhere and was particularly rough on the already isolated South American country, where flights abroad are few in regular circumstances.

While the Commissioner of the OAS General Secretary for the crisis of Venezuelan Migrants and Refugees David Smolansky has spoken of some 43,000 Venezuelans stuck out of their country and other reports give different figures in different countries, the chavista government labels returning migrants as “bioterrorists” and uses them as an excuse to take unilateral and noxious measures, like shutting down the Venezuelan border with Colombia, where dozens upon dozens of Venezuelan citizens were literally stuck on the highway, with nowhere to go, and a very contagious virus going rampant.

For Angel, this invisible barrier is indeed very tangible. For Marcel, a 74-year-old Venezuelan art salesman stuck in Miami, the prohibition to return to Venezuela exposes him in more ways than one: “I’m HIV+ and, being a tourist in another country, I didn’t have access to treatment for a month and a half,” he says before making a list of everything he’s been through during the last six months: “I spent $450 on the visa and was left with $100 on my account. I was kicked out of my sister’s house and now I stay at a friend’s house. I try to be invisible, help out as much as I can, trying not to think about my own home.”

Marcel hasn’t gotten any help from the embassy articulated by Juan Guaidó’s caretaker government, and neither did Angel:

“I wrote to (the ambassador appointed by Guaidó in Panama) Fabiola Zavarce and talked to her many times,” Angel says. “She said she was willing to help, but in reality there just wasn’t much she could do.”

Caracas-based Láser Airlines did offer Angel an option, but he decided against it: “Láser would take us to Havana, and from there we’d take another flight operated by (the Venezuelan state-owned airline) Conviasa to Caracas. Of course we declined; we were just not going to run the risk of getting stranded in Cuba.”

“I’m HIV+ and, being a tourist in another country, I didn’t have access to treatment for a month and a half.”

In the end, he had to fix everything himself. Since his fiancée couldn’t enter Spain because she’s not a citizen, and Angel couldn’t enter her country of origin (Canada) for the same reason, they just booked a flight to the U.S., which did have a humanitarian route with Panama. “It took us three days in Miami,” Angel says. “There were some complications, but once we got married everyone was very helpful and we entered Canada, through Toronto. We’ll just have to do a symbolic celebration with our families once this is all over.”

Opacity, Improvisation and Chaos

Since the Venezuelan National Institute of Civilian Aeronautics shut down all civilian flights last March, 14th (allegedly until September 12th, but prolonged for another month), humanitarian and repatriation flights have been a thing of uncertainty—even for the authorities of other nations. Flights are supposed to be coordinated between Venezuelan authorities and their counterparts abroad, but the truth is that the opacity with which the Maduro regime behaves isn’t an exclusive experience of Venezuelan citizens.

The sixth humanitarian flight from Caracas to Madrid, for instance, was programmed for July 25th and delayed for over four days by Venezuelan authorities, without justification to the Spanish General Consulate. It fell on the Spanish Consulate to contact the passengers and explain that the flight wouldn’t happen, unable to assert if this was a delay or the actual cancellation of the flight, since the Venezuelan government was giving “no explanations.”

That sixth flight (along with a seventh) finally left Venezuela on July 30th, but the same problem later occurred with the Caracas-Paris Air France flight scheduled for September 6th, a flight that had to be canceled, despite having all the sanitary requirements—again, no explanations from the Maduro regime—and although two flights were recently allowed to leave from Caracas to Panamá, the repatriation of Venezuelans abroad wasn’t authorized.

On May 5th, 250 Venezuelan citizens flew from Santiago de Chile to Caracas on a flight from the repatriation plan Vuelta a la Patria—that existed (mostly as a propaganda tool) way before the pandemic, due to the massive flow of people leaving the nation. Since then, the repatriation work has been up to private airlines authorized for the task, the latest case being the Buenos Aires-Caracas flight of August, 20th, for which the airline Estelar demanded a fee that went from $450 to $790, and additional expenditures for a 14 day quarantine at the Eurobuilding hotel, where prices reach $100 a day.

There’s yet another way to come back for those Venezuelans stranded abroad. As depicted on a recent BBC piece, there’s a particular list for those stuck at the theoretically impermeable border between Venezuela and Colombia, closed until October, 1st. For the sum of $40, you can get preferential treatment when the time comes for the borders to re-open and resume the journey back.

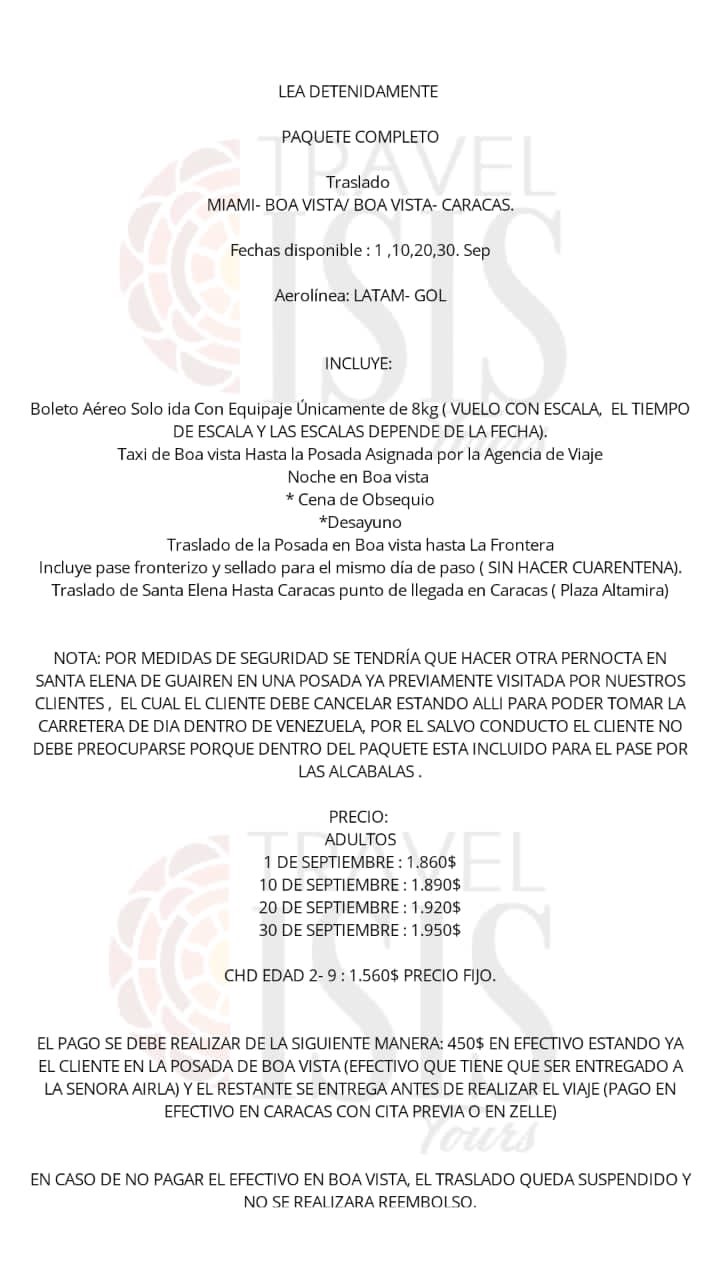

There’s also this document, making the rounds on social media:

For close to $2,000 a head, Venezuelans stuck in Miami could make the trip to the city of Boa Vista, Brazil, and cross into Venezuela by road and into Caracas, more than 1,200 km away. The “package” guaranteed no hassle by authorities and “no need to quarantine”, specifying that the agency, Travel Isis, wasn’t responsible for any trouble at the border, and couldn’t guarantee the crossing into Venezuela as offered.

The uproar provoked by the offer caused Isis to withdraw it, but the BBC article mentions the existence of other packages by other agencies, on the same route.

Venezuelans on Their Own

Maleyva Zambrano, a 43-year-old psychologist, is now quarantined in one of three shelters (one of which is free of charge) that the Maduro regime assigned for 140 Venezuelans who were stranded in the Dominican Republic and just came back. For her, it was almost six months of permanent activism to make the journey home—and there’s still partners of struggle left behind.

“The attitude of the ambassador contrasts with what seems to me as a lot of bureaucracy. It’s inconceivable that it took so long for the Venezuelan government to allow a trip back.”

“I spoke with the Venezuelan ambassador Alí Uzcátegui and I, for one, feel his concern was genuine,” she says. “Both he and his secretary Iván Salerno called me on my phone, the ambassador held a meeting with us in person, and he talked to us directly.”

For her, it’s very easy to imagine why; beginning with just a handful of people demonstrating outside the offices of different authorities, from the personnel at the airport to the Dominican Ministry for Foreign Relations and the Episcopal Conference, the group grew to 170 Venezuelan citizens raising their voices. The Venezuelan Embassy works thrice a week (Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays), and every single day the group was there, before the first worker arrived, until the last one left. This, mind you, was in a residential area.

“By just showing up, we were inconvenient,” she says. “We’re travelers, some of us with expired permits to stay, and we have no access to the Dominican health system. All of this moving around to get a flight back, which is a full-time job, exposed us to the risk of coronavirus. So we’re uncomfortable for the authorities. And the attitude of the ambassador contrasts with what seems to me as a lot of bureaucracy. It’s inconceivable that it took so long for the Venezuelan government to allow a trip back.”

Maleyva’s case is archetypical of the problem: Dealing with a family affair, she left Venezuela for the U.S. and that’s where the global lockdown caught her. Patience gave way to despair when the first month passed, on April 12th, and then a second month came without answers by American authorities. Venezuela doesn’t have an embassy in the United States—except for the office of Carlos Vecchio, appointed by the National Assembly and recognized as the legitimate ambassador by Washington—and to stay beyond what’s legally allowed, she had to pay a steep sum of $500. With her passport months away from expiring, she started feeling that legal purgatory of those without papers to remain abroad, and without consular authorities to reach out for help. Very much like Angel, she realized she was on her own.

“I went to the Dominican Republic because it was closer to Venezuela, and I could pay a fine at the airport for overstaying, less hefty than the American,” she says. “When I got there, there was already a group of Venezuelans stuck in Santo Domingo.”

The end, at least for her, came abruptly: On September 10th, two Conviasa flights were coordinated between the Venezuelan Embassy and the Dominican government, reaching Venezuelan soil that same afternoon. The travelers did pay for their own ticket ($120) and their first PCR test ($75), but Maleyva is quick to point out that the treatment they’ve received has been quite decent, particularly from the Conviasa people and the embassy personnel. The struggle, however, carries on, with over a hundred more Venezuelans still in Santo Domingo.

Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights explicitly states that “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country,” while Article 50 of the Venezuelan Constitution is specific on how all Venezuelans “can enter the nation without need of any authorization, and no act from Public Power may impose an exclusion on Venezuelans from the national territory.”

For Maleyva, the bitter wait is over, but she’s hoping hard that what happened with her return isn’t an isolated event.

Marcel, on the other hand, is still in Miami and doesn’t believe his problems will be solved by just going home. His apartment in Parque Central, Caracas, was already in bad shape when he left, surely deteriorating after six months uninhabited. Marcel’s roommate had to leave the apartment to travel back home to the Venezuelan plains due to unemployment. “I live from my pension,” says Marcel, “My roommate didn’t pay rent, but he’d pay for the food. With him gone, I’m not sure I’ll be able to survive the pandemic. Nothing’s certain anymore.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate