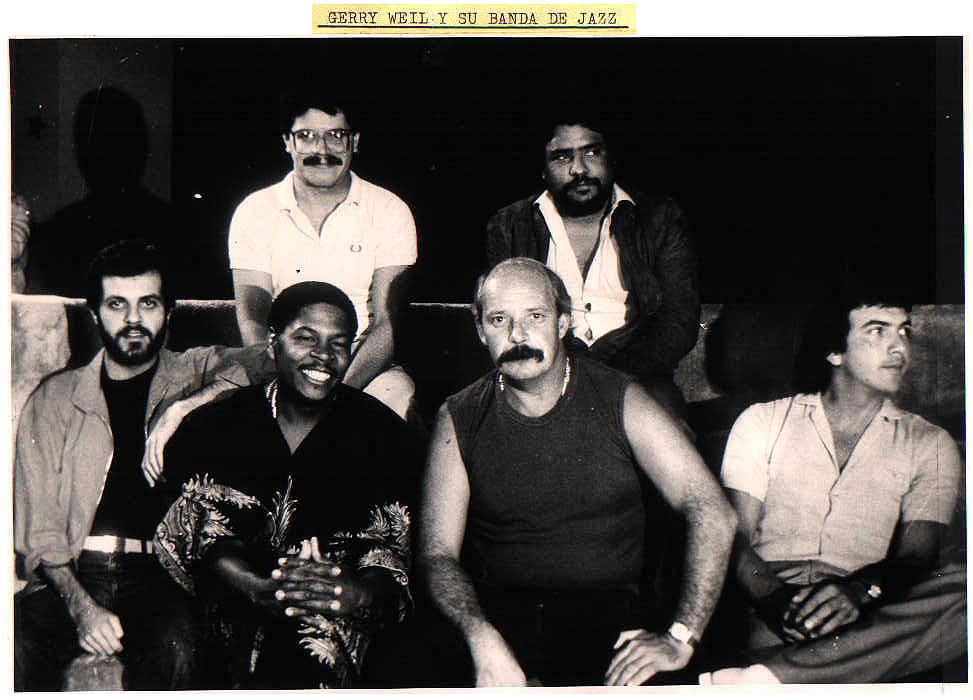

The Venezuelan Jazz Hippie That Never Stopped Reinventing Himself

At almost 81 years old, Gerry Weil releases an album plentiful of collaborations with young musicians, full of the innovative energy that made him one of the founders of Venezuelan jazz

Photo: María Fernanda Lairet

Sometimes the most sublime of human expressions comes from its darkest side. The story of Gerry Weil begins with a war, the one with Aryan supremacy delirium, which exploded the same year he was born, 1939. When it was over, a renewed frenzy for New World rhythms amongst troops and occupation rifles were reignited, taking into a sound that would change his life to Austria from his childhood.

“I lived with my grandmother as a refugee, in a country house on the outskirts of Salzburg, after a bomb destroyed our home in Vienna, at the end of the war. I would play with other kids on a bridge close to a river, where we would see German soldiers: defeated, starving, picking up cigarette butts off the floor… and one day, they were gone. An American tank was there. It was the first time I ever saw a black man. It was an American soldier and he took out an antenna and his radio went on, sa-ba-di, du-du-di, du-du-di, du-du-di. Wa-wa. It was ‘In the Mood’ by Glenn Miller! I just stood there, with my eyes wide open. I went, ‘What’s that beautiful sound?’ And from then on, whenever I was in the country house, I tuned into the American troops’ radio.”

That’s the start of a journey for a man who proudly claims to be Venezuelan, “although my papers say I’m Austrian,” with a Caribbean joy that contrasts with his clear blue eyes and his sun-tanned and deep-lined skin, taking prose by storm with his rough voice and lively speech, even though his native tongue makes his Spanish trip. The story of a man that lit up the Venezuelan culture cosmos with an explosion that moved a music genre closer to another void of native rhythms. A man whose legacy goes beyond decades, rhythms, fusions, and genres, blending three alien concepts until he came along: Austria, jazz, and Venezuela. Ever since, Gerry Weil is known as “the maestro of Venezuelan jazz”.

At the end of the day, that’s what the genre is all about: music that’s made up of many others. “Jazz tradition is permanent change,” claims jazz musician Robert Glasper. “If you stop changing, you stop growing, you’re not following tradition. If people say ‘you can’t do that’, it means you’re doing it right.”

And that’s what Weil wanted. What he reinvented from national folkloric genres starting at its roots, in order to create a new sound that was far removed from any innocent layering. What he blended with electronic, rock, funk, blues, salsa, symphonic music, and even hip-hop in an eternal innovation journey that matched his love for the beach, surf, karate, languages, cats, his family life, and a deep spirituality. A life, you might say, that’s an allegory of jazz.

From Vienna to La Guaira

But none of that has happened yet. For now, young Gerhard Weilheim is 17 years old, and is on a train ride with his mother and stepfather to Genoa, where he takes a transatlantic boat to the New World. He saw then, from the prow, the bright colors that glistened from the port of La Guaira in an early morning in 1957. “I’m staying here,” he told himself, and burned his sails in Caraballeda.

“We lived there for two years. I worked as a night doorman in the Santa María building of the Puerto Azul Club. They’d give me the keys at night and I found out that they had a piano brought in for the opening of the El Galeón club. I would sneak in, and since I was blond, people didn’t think I was an employee,” he laughs. “And I would sit down to practice. The building managers realized I played a bit, doubled my salary and allowed me to play in the club restaurant at noon.”

Two years ago he played that same piano, in that same club (now as a member), and two years after his arrival, he settled in Caracas, teaching himself the piano with eight to ten hour long sessions, every day, for thirty years.

Daring Jazz

The story of what came later is compiled in 16 records. At least that’s the number recalled by his son and manager, Gerhard Weilheim, whose excitement when he talks about Gerry has no boundaries. His debut album, El Quinteto de Jazz de Gerry Weil (1968), is made up of covers of some of his influences and gives a glimpse into his first compositions, like “Expressions N°1”, an acid jazz soaked in the hippie psychedelia of the times. El Mensaje (1970) has a cleaner sound, with six original songs that can be defined as big band rock. In the zenith of that creative moment, from that five-piece band, one of the most avant-garde sounding bands was born: La Banda Municipal.

“We were so avant-garde that no label would record us. Vytas (Brenner) recorded albums like Ofrenda because it was more mainstream. But we were the crazy ones at the time. I think we were ahead of our time. If you listen to La Banda Municipal today, it sounds current.”

Weil remembers those years when the group was a cult reference amongst music lovers, who enjoyed their only live recorded performance (Valencia Municipal Theater, 1974) in bootlegged cassette tapes sold by street vendors in the Plaza de los Museos, in Caracas. Fortunately, journalist Gregorio Montiel Cupello rescued a copy of that recording thirty years later, producing the only legitimate and remastered register of the band to date.

But the band’s days were numbered: several of its members took on other projects, including Weil, who would quit a year before the group’s dissolution in search of a spirituality that, from the hippie point of view, can only be found distancing yourself from the system, and being in contact with nature. They used to call it “the drop-out”.

Mérida: The Journey

Weilheim Jr. remembers cheerfully his childhood in the mist, natural spring water and wildlife. Without electricity, the life of the Weilheims (Gerry, his wife Omaira, and their sons Alexander and Gerhard) would go by among rose bushes, fruit and vegetable crops. Meditation, reading the classics and music were their daily chores in a small farm between Jají and La Azulita, Mérida state in the Venezuelan Andes, where Gerry began to study Bach and wrote songs like “Mañana de campo en abril”.

“I always head for the countryside, in every way!” he laughs. “Like a leopard, I never change my spots!”

But the trip had a return ticket. The need to raise their sons in civilization made them return to Caracas, where reality slaps the maestro in the face. Without any income or a home of his own, he understood that six years away from the system doesn’t go by without consequences. It was 1981. The world had changed.

Gerry, The Maestro

A mandatory adjective in Gerry Weil’s life is “teacher,” as four generations of musicians trained in almost 40 years can attest. Maybe not everyone knows his name, but many know of his students. “The place occupied by Gerry in music education in Venezuela is huge,” says his biographer and author of Al ritmo de Gerry Weil, Cristina Raffalli. “The part it takes in building a country is enormous, because when you spend 40 years of your life passionately dedicated to your students, it’s a unique kind of work for your country. He educated not only with a musical vision, but also teaching attitude towards the creation, veneration, and respect of music.”

Guitarist Diego Ayala confirms this mystic sense of the maestro:

“He’ll make you feel an incredible humbleness towards the mystery of music. How lucky we are to play with something so abstract and mysterious. That we can understand it little by little by studying and practicing it.”

This is perhaps one of the maestro’s more known faces. What few people know is that he began this practice as soon as he arrived in Caracas, after that drop-out.

“I started teaching with my bicycle all over Caracas. I would put up flyers in pharmacies and supermarkets promoting ‘music lessons.’”

Urban legend says that, at the time, Weil had mail ordered lessons from the famous Berklee College of Music, but the reality is different:

“I never enrolled at Berklee. I had a student who did enrol in the eighties, but he didn’t speak English. So he would pay me to study the lessons they gave him and I would tutor him by explaining the assignments. He graduated, I learned, and I registered all that in my system. Indirectly I was a Berklee teacher.”

Raffalli’s vision from her experience with Weil’s students is that he teaches what every good teacher must: the sense of freedom when creating something. Finding their own artistic voice as a reflection of themselves. And Diego Ayala remembers the maestro’s definition of music like a mantra:

“A gesture of love to us by the divine and our answer with passion and thankfulness.”

The Spiritual Side of Music

That spirituality has also impregnated his work, witnessed in his latest album, Kosmic Flow, an album where the jazz and hip-hop fusion base makes the word “experimental” fit into a genre that by definition, is experimental. Swing and R&B melodies appear with funk guitar strums, reggae figures and an ever-present hip-hop sample beat that would even make it in a trap song.

One thing this album has to boast about are the collaborations, the distinctive feature in any hip-hop album. Kosmic Flow gathers artists within the genre, such as Apache, Afreeka, Ron Lion The Monster, the band Free Convict, beatboxer Jhoabeat, Sibilino (former Tres Dueños), OneChot, McKlopedia, and the veteran Costa Rican hip-hop artist Toledo.

Other guests include, besides beats and rhymes, guitarist Rafael Antolínez (Caramelos de Cianuro and Le Cinema), Henry D’Arthenay (La Vida Boheme), Chipi Chacón, vocalists Laura Guevara, Hana Kobayashi, Liana Malva, and Trina Medina, drummer Orestes Gómez, and the Venezuelan music youth band Ensamble B11. This album was recorded and produced between Vienna, Caracas, Medellín, Miami, and Mexico City. The artwork was created by Brooklyn-based Venezuelan designer Luispa, and reproduction was made in New York.

That’s the music wrapping for songs like Ima Koko Ni (Here and Now, in Japanese), a hip-hop track that pays tribute to Venezuela and where the five principles of Reiki are recited: “Just for today, do not worry, do not be angry, be grateful, work eagerly and honestly, be kind.” Rap de las Tortugas carries an environmental message; Achanta el Pure e’ Pana is about the importance of forgiveness; and his remake of Govinda Shakti, with Hindu melodies, calls for that religion’s vision of peace and love that he adores.

It’s the last of three albums he has released in a year, along with Live in Vienna (2019) and Gery Weil & Simón Bolívar Big Band Jazz (2019). And although he maintains that 16 albums is a small number considering his musical trajectory, his work is taken as musical reference by artists in every genre across the country. That’s where his producer side comes from too, which he defines as another way of teaching, because he guides the artist in music, art, and even spiritual concepts.

“It’s not my forte, but a musician has to know about everything, including production.”

Primogénito, by María Rivas (1990); En Descomposición, by Desorden Público (1990); and the EP by the band Tulio Chuecos (2007) are the three records he’s credited in as producer, not including the individual tracks he’s worked on with other artists like OneChot. “Tulio Chuecos was a band made up of excellent musicians from the UCV’s Architecture school. It was the closest thing to Radiohead in Venezuela,” the maestro points out.

Peace and Love

Those who know him agree that Gerry has one flaw: his stubbornness. But is it really a flaw for him?

One day in Vienna, when he was eight years old, he insisted so much that he wanted to be a musician that his grandmother took him to a conservatory. After he took the test, the music teacher concluded that his love of music was incompatible with his ear. His stubbornness would give him, 70 years later, poetic justice: in the same city where someone told him he would never be a musician, he recorded Live in Vienna, in 2018, in a crusade filled with the effort and sacrifice a young musician goes through.

It was the first album in this relaunching period, or how Weilheim calls it, “the rebirth” of his father, after a bout with colon cancer—while not too serious, it was a wakeup call: with a music career such as his, he still couldn’t afford the surgery.

“I was at home with my mom and we called to say hello,” guitarist Diego Ayala remembers. “That’s when he tells us, rather anxiously, that they had found some tumours and that he didn’t know how to get the money for the surgery. I never doubted the fact that we would be able to raise the funds, but I was surprised by everyone’s generosity, how quickly we reached the goal and how we surpassed it.”

From that moment on, his son Gerhard swore that as long as he was alive, he wouldn’t allow that to happen again. So he’s been his manager for three years. He’s had not only to relaunch his father’s career, but land him in the country’s economic reality.

At almost 81 years old, Weil continues to teach from his home in Sabana Grande, Caracas, and is working on international projects with his son. It’s the least one could expect from someone who’s hoping to reach 120 years of age making music and exploring new facets, like he did with surf and karate, with which he accompanied his two sons across the world as an athlete (karate) and team manager (surf). Never letting go of the woman that has kept him going: his wife, Omaira González.

“If my soul had a Bolívar Square (a must in all Venezuelan towns), I would put up a statue of Omaira in it. It would’ve been impossible for me to achieve what I did with my life without the wonderful presence of this person that left everything behind; her career as an artist and dancer, to raise my children and be my life partner for fifty years of marriage, which we celebrated in August. She deserves a statue made of the best marble, or gold, for putting up with this nut,” he says.

That’s how days go by for the maestro Weil, harvesting love, forgiveness, discipline, work, and happiness as a philosophy; a firm believer that you can only find these things inside you and you don’t really need that much outside. In his case: being barefoot on the beach or at home, a cold beer, his daily meal and a tuned piano. That’s enough for him to keep making music, to keep lighting up the jazz cosmos with an eternal recreation of a genre. A perpetual motion, like his own life, of an eternal Venezuelan jazz hippie that never stops reinventing himself.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate