Factories of Death: the Jails of the Maduro Era

On May 1st, 47 prisoners were executed in a confusing event in Guanare. Venezuela has a horrible history of prison massacres

Photo: Sofía Jaimes Barreto

In the midst of Venezuela’s coronavirus quarantine, a gruesome event took place on May 1st. 47 inmates were murdered and 71 were injured in the Centro Penitenciario de los Llanos Occidentales (CEPELLA), in Guanare, Portuguesa, after they confronted the authorities, according to the official version.

This alleged clash isn’t only questioned by the victims’ families, but also by several NGOs and María Beatriz Martínez, a National Assembly deputy for Portuguesa state. “The information regarding the massacre is still quite blurry,” Martínez said on her Twitter account. “They’re trying to present it as a failed escape, but everything points to a riot caused after the prison inmates were starved by the guards.”

The international press has reported about how penitentiaries in Venezuela (and the rest of the region) symbolize awful administration and corruption. They also display the power gang leaders can have, who not only continue committing crimes from inside the prison, but also leave as they please and use the jails as headquarters for their operations, backed by the state, where criminals live well and are kept safe from their enemies. The influence of these jails over the rest of the country is so strong that even prison slang has percolated into the nation’s climate of insecurity; the use of the word pran, formerly applied only inside prison folklore for criminal leaders, now refers to any criminal leader in cities or mines.

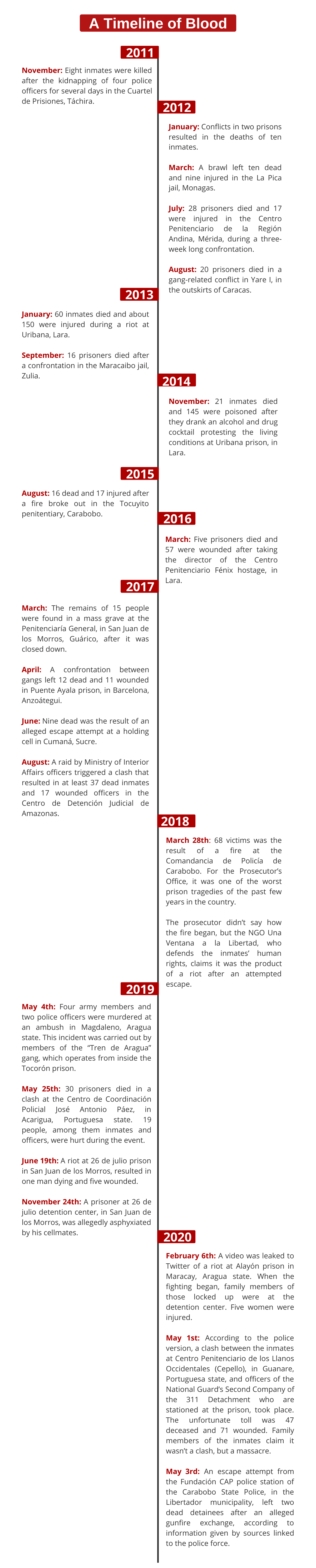

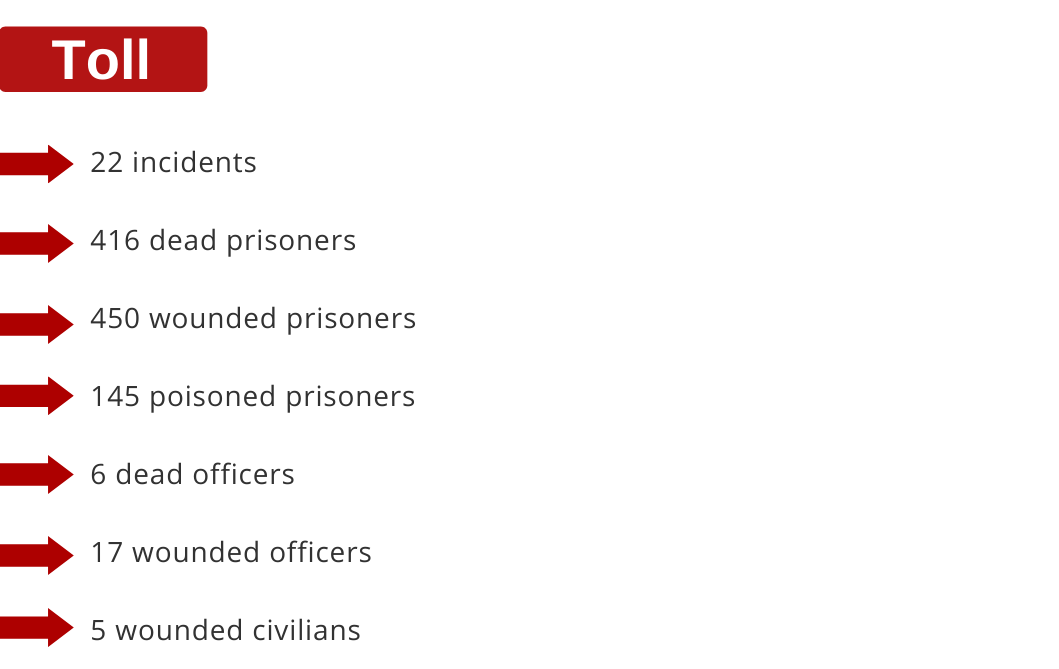

What is lesser known is the immense degree of violence and how often these massacres occur inside prisons, even before the arrival of chavismo (a riot in 1994 ended with over a hundred dead inmates), although they’ve certainly become chronic in the last few years. The event in Guanare reminds us of the over 20 bloodstained incidents that have occurred in Venezuelan prisons since Iris Varela was appointed by Hugo Chávez as Minister for Penitentiary Services in 2011. Since then, there have been over 420 dead inmates and officers, and at least 473 wounded inside Venezuelan prisons.

In addition to all of this, at least five civilians have been wounded in these violent events, and in November 2014, 145 inmates were poisoned after drinking an alcohol and drug cocktail, as a protest for the living conditions in Uribana prison, Lara; 21 prisoners died.

Minister of Violence

Iris Varela, a lawyer graduated from Táchira Catholic University, associated with Hugo Chávez since his failed coup attempt in 1992, was a deputy in the National Assembly for Táchira from August 2000 until July 26th, 2011, a period in which she became well-known for being one of the most radical voices within chavismo—she frequently voiced her opinion on how violence should be used against enemies of the revolution. Only seven months after being re-elected for a new term, she left her seat to take on the Ministry for Penitentiary Services, which Chávez created just for her, as an apparent solution to the bloody crisis that had developed, disclosing the overpopulation, low hygiene, and neglect on the inmate population. However, with her at the helm of the ministry, things didn’t improve.

Her critics have always rejected her because of her aggressive and recalcitrant attitude towards opposition leaders—whom she constantly threatens to imprison through social media—as well as her photographs with pranes.

On July 26th, 2017, she was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department and on March, 30th, 2018, she was sanctioned by the government of Panama, after being considered high risk for money laundering, financing terrorism, and financing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

In September 2018, NGO Una Ventana a la Libertad, which defends inmate human rights, published a report saying that Iris Varela’s performance as head of the Ministry for Penitentiary Service was negative. The report goes on to describe how, during her administration, the war between pranes to control prisons has intensified, as well as the drug dealing business, car theft, extortion, and prostitution both inside and outside of jails.

Four Solutions

Carlos Nieto Palma, coordinator of Una Ventana a la Libertad, has four concrete proposals to improve the living conditions of inmates in Venezuela—as well as preventing future tragedies.

Reduce the procedural delay. 70% of prisoners in Venezuela haven’t been sentenced, leading to overcrowding even in Preventive Detention Centers, where people aren’t supposed to stay for over 48 hours, and are now used as permanent prisons.

Build new penitentiaries. There are places in Venezuela without prisons, or with reduced detention centers, such as Amazonas, Cojedes, Delta Amacuro and Zulia. Overcrowding of Preventive Detention Centers has grown in these states.

Decentralizing prisons. Let them be overseen and administered by governors and eliminate the Ministry for Penitentiary Services.

Inmate classification. Prisoners of all kinds can’t be placed in the same space; this leads to prisons where political prisoners or those with misdemeanors are placed with criminals that have terrible records.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate