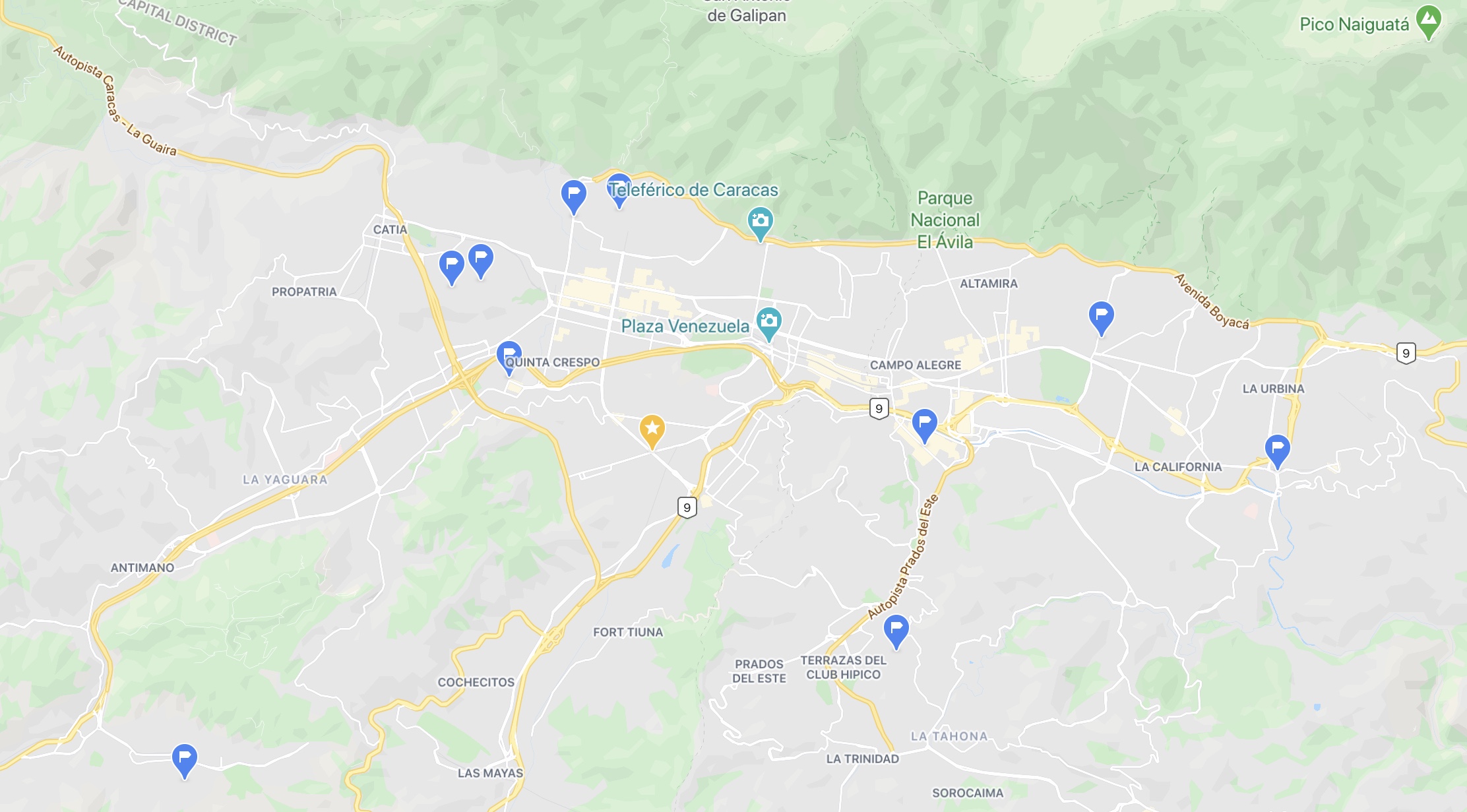

Mapping Quarantined Caracas

You may be able to force caraqueños to wear masks, but in a city where most people can’t afford to stay at home for days, it will be a paramount challenge to enforce a quarantine. Even for a dictatorship.

Photo: Violeta Rojo.

These testimonies show us how the quarantine impacts Caracas in different ways depending on where you live. The only constant, however, seems to be the unlikeliness of being able to keep people indoors for several weeks. Especially those who live by the day.

You may be able to force caraqueños to wear masks, but in a city where most people can’t afford to stay at home for days, it will be a paramount challenge to enforce a quarantine.

Jesús, northwest

Water is scarce. I don’t know how people who must work on the streets every day are going to survive. The colectivos are imposing a curfew in some areas and selling food at whatever price they want. This is living under a dictatorship, but with irregular armed groups as the authority.

Ana, northwest

So far, in the 23 de Enero neighborhood people have obeyed the quarantine, more than I expected, maybe because we all know what it means to get sick in this country, especially if you’re poor. Some people got organized to clean the stairs and the buildings’ corridors, and colectivos tour the streets to remind us that everyone must remain at home, including those guys drinking booze at the corners. During the morning, we have no option but to get out for groceries: none of us are equipped to stay at home for weeks.

Iván, north downtown

North of Baralt Avenue, the gas station is closed and you cannot access Boyacá Avenue. Just a few cars are going on Baralt and no one is walking around. The church San José del Ávila and its school are closed and we’re not hearing the horns of buses going from Capitolio to Mecedores. Everything is silent.

“Just a few cars are going on Baralt and no one is walking around.” Photo: Iván Reyes.

María Fernanda, Cotiza, north of downtown

The highway that crossed the city, la Cota Mil, is closed. National Guard (GNB) and FAES officers patrol several times a day. Only grocery stores are open, from nine to two, and the situation with water is critical: we get supplied only once a week and you see masked people carrying water all the time, or getting it at the foot of the mountain. We’re also doing hours-long lines for cooking gas. Power is going off every day, for two, three hours at a time, and masks went from costing 30,000 bolivars to 200,000. I’m not making any money as a manicurist and the anxiety is starting to show up at home.

Víctor, southeast

One day after the quarantine was declared, on March 14th, the east of Caracas went through its fourth January the 1st of the year. That day I went to a local drugstore in Las Mercedes (Baruta municipality) for a few groceries. A small army of people, all in surgical masks of different degrees of effectiveness and some wearing gloves, had the same idea. It was packed. Perhaps a little more people than there should be—both inside the drugstore and outside). We were all stocking up for a sort of hibernation of unknown duration and while some folks were out for cookies and ice cream (seriously), others bought diapers for adults and meds, the type of things that you just can’t do without.

After 2:00 p.m. there’s no traffic in the street. Middle-class Baruta doesn’t feel like an area that has been closed off, besides the medical items on everyone, the vibe could pass for that of a holiday. It doesn’t feel panicky yet, just an eerie repetition of that January 1st feeling that we’ve had so many times in three months since the year started.

Eusebio’s, a local and usually crowded spot, is rather lonely during the quarantine. Photo: Violeta Rojo.

Violeta, southeast

Empty streets, crowded supermarkets, everyone with masks, some people with gloves. No one keeps the distance. People touch you all the time, as always. Next to a closed liquor store, I saw a group of guys drinking beer, removing their masks for every sip.

Samuel, northeast

At Los Dos Caminos, almost everything is closed, the few pharmacies open demand masks to grant access. In Petare, you can see many masked people on the streets; at Rómulo Gallegos Avenue, few supermarkets open with long lines; there’s no access to highways yet many, many cars on Francisco de Miranda Avenue. Very few actual pedestrians, but lots of cars. On Tuesday, I went twice to the Millenium mall, and they were controlling access with fences and security guards, and only one Farmatodo drugstore and a little supermarket were open. The usually crowded adjoining square was empty and some masked, stubborn people were there waiting for buses for Guarenas and Guatire.

In Petare, life goes on (with masks). Photo: Génesis Carrero.

Aglaia, southwest

In Venezuela, this quarantine is not so strange because of our continuous crisis. However, since March 13th, we do see changes after the government went from indifference to a bunch of sudden measures. I live near a National Guard post, so I can see any military when some military operations are deployed. On Monday 16th, masked GNB soldiers were scattered across the bridge that connects with downtown and installed checkpoints all over the eastern access to El Paraíso. It’s like a partial curfew. Most of the stores are closed in the afternoon.

“Since March 13th, we do see changes after the government went from indifference to a bunch of sudden measures.” Photo: Aglaia Berlutti.

Daisy, southwest

On the highest parts of Caricuao, the streets have been empty since March 15th. The farmers market that works from Tuesday to Thursday shut down after one day, by order of the National Guard. At the Unicasa supermarket, you need some kind of mask to enter, and the Zoo was closed immediately when the first cases were reported.

Natasha, Guatire, east of Caracas

After spending four days at home, I went to fill my car’s tank and get groceries, and all entry points to Caracas were closed. You can only reach the city from Guarenas if you’re a doctor or are shipping food. Here in Guatire, everyone’s using masks, and visiting, swimming at the pool and playing in the basketball courts of my neighborhood are all forbidden.

Omar, Tanaguarena, north of Caracas

This little vacation neighborhood is ghostly now: very few people on the street and pools inside buildings were closed by their janitors. At Caraballeda, we saw long lines around the supermarkets and Farmatodo, everyone hoping their masks would protect them from all harm… while disregarding the one-meter distance you’re supposed to keep between each other.

“This little vacation neighborhood is ghostly now.” Photo: Omar Mesones.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate