Dollars in Barrios Are Not a Privilege Anymore

With the growing unofficial dollarization of the Venezuelan economy, most transactions in the poorer areas are done through foreign currency. This has generated a sense of prosperity in the capital, but it’s also one of the reasons the gap in social inequality has grown.

Photos: Gabriela Mesones Rojo and Génesis Carrero

The doors open in the subway car at Agua Salud station and a vendor sells seven chocolates for a dollar. In the Los Tres Reyes Magos Square in front of the subway station—which is free of charge because there’s no cash to pay for the service—there’s a long row of food stands where they also take foreign currency: $5 for a pepito and $1 for a soda, although some pay Bs.S. 75,000 (the price for a “parallel” or black market dollar this weekend of 2020). Further down the road, in the central area of 23 de Enero, a group of friends is drinking beer in La Milagrosa and threaten the owner with paying in bolivars. “The only green on me is this shirt I’m wearing,” one of them says, laughing hard and ordering another round of beer.

23 de Enero’s view from El Observatorio. Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo, Caracas, 2020.

A Dollarized 23

Gregory, the liquor store owner, hasn’t had a point of sale for months anyway. If someone wants to pay in bolivars, they can do so only through a wire transfer. Gregory opened La Milagrosa 16 years ago and still feels his business hasn’t stabilized yet. “Venezuela has a risky economy. You have to adapt and try to do what’s best for your business,” he explains. La Milagrosa is a liquor store that opens its doors to locals who want to get together, have a drink, laugh and, today, talk about the dollarization: “There’s a little crackhead that lives down the street. A junkie, homeless, with no job. No one has bolivars, so he asks for a dollar. Some might give it to him.”

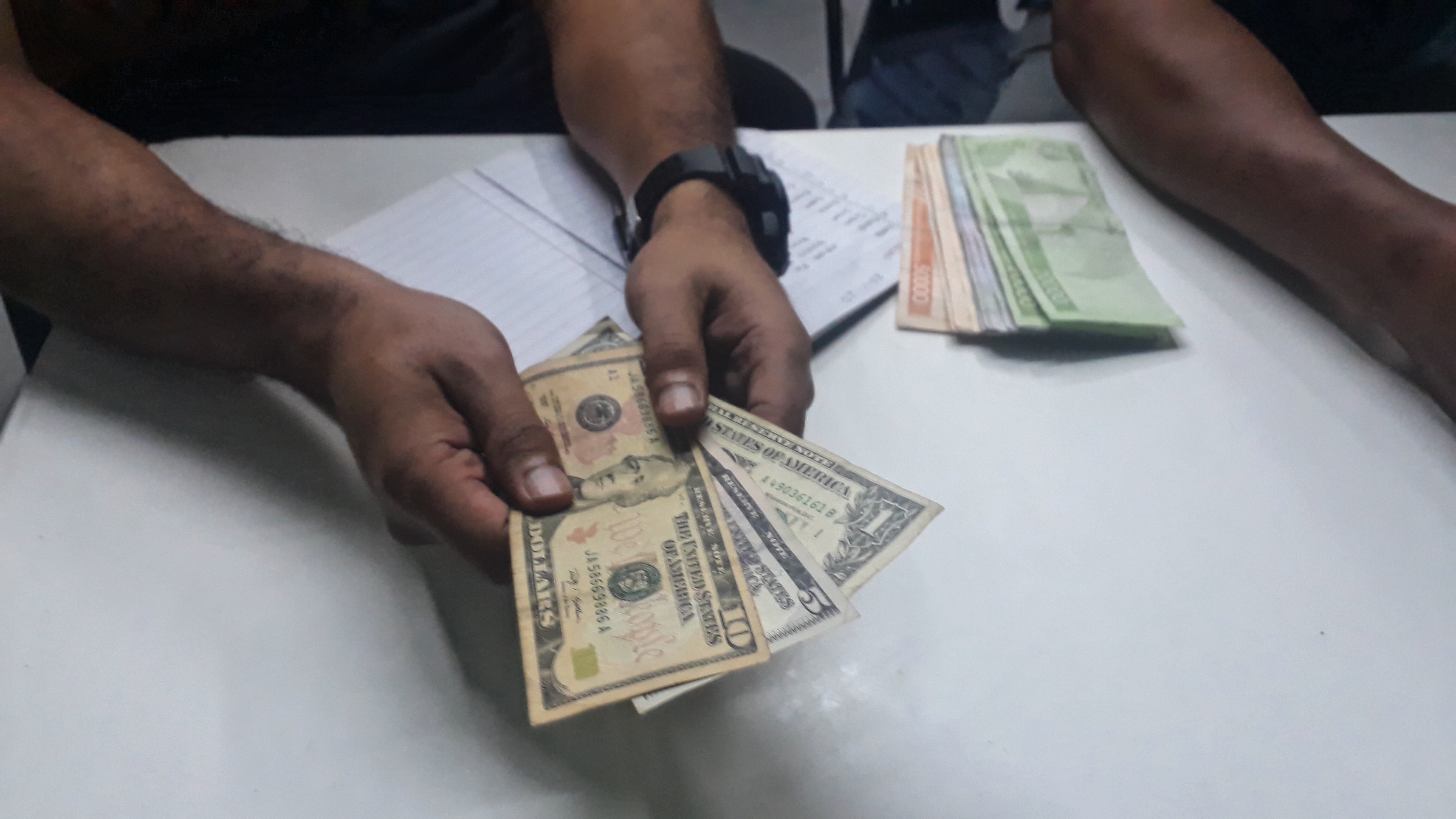

Gregory realized, early in 2018, that more and more people were looking to pay with dollars, and during the March blackouts last year, the dynamic was established. By the last trimester, more customers paid with U.S. dollars than with bolivars. Gregory accepts the national currency, but the prices for his products are subject to the dollar’s rate of the day, which forces him and his clients to recalculate the amounts for each purchase and the currency fluctuation every day. Buyers must pay a part in bolivars or buy more items, in order to reach a round number. Now, Gregory has added to his list of chores the acquisition of small bills, so he can give change: “People pay with $1 and $5 bills, but we also get a lot of $20 bills. If I tell a customer that I don’t have any change and they have to buy more stuff, they never come back. So I must always keep small bills in hand.”

He adds that writing invoices in both currencies doesn’t give him much trouble and the only downside with the dollarization is that it has completely sidelined the bolivar. “I think it was necessary, and I believe it’s a positive thing. People have been saving their money again, little by little. Some people may only save $3, but now they have $3 they didn’t have before.” However, Gregory thinks that hyperinflation is the reason why foreign currency is now used across the city: “The real problem can’t be solved with this. Prices keep going up, no matter which currency you use.”

Iván own a motorcycle rapair shop, and he says few people pay in bolivars: “It’s not even worth calculating the exchange rate.” Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo, Caracas, 2020.

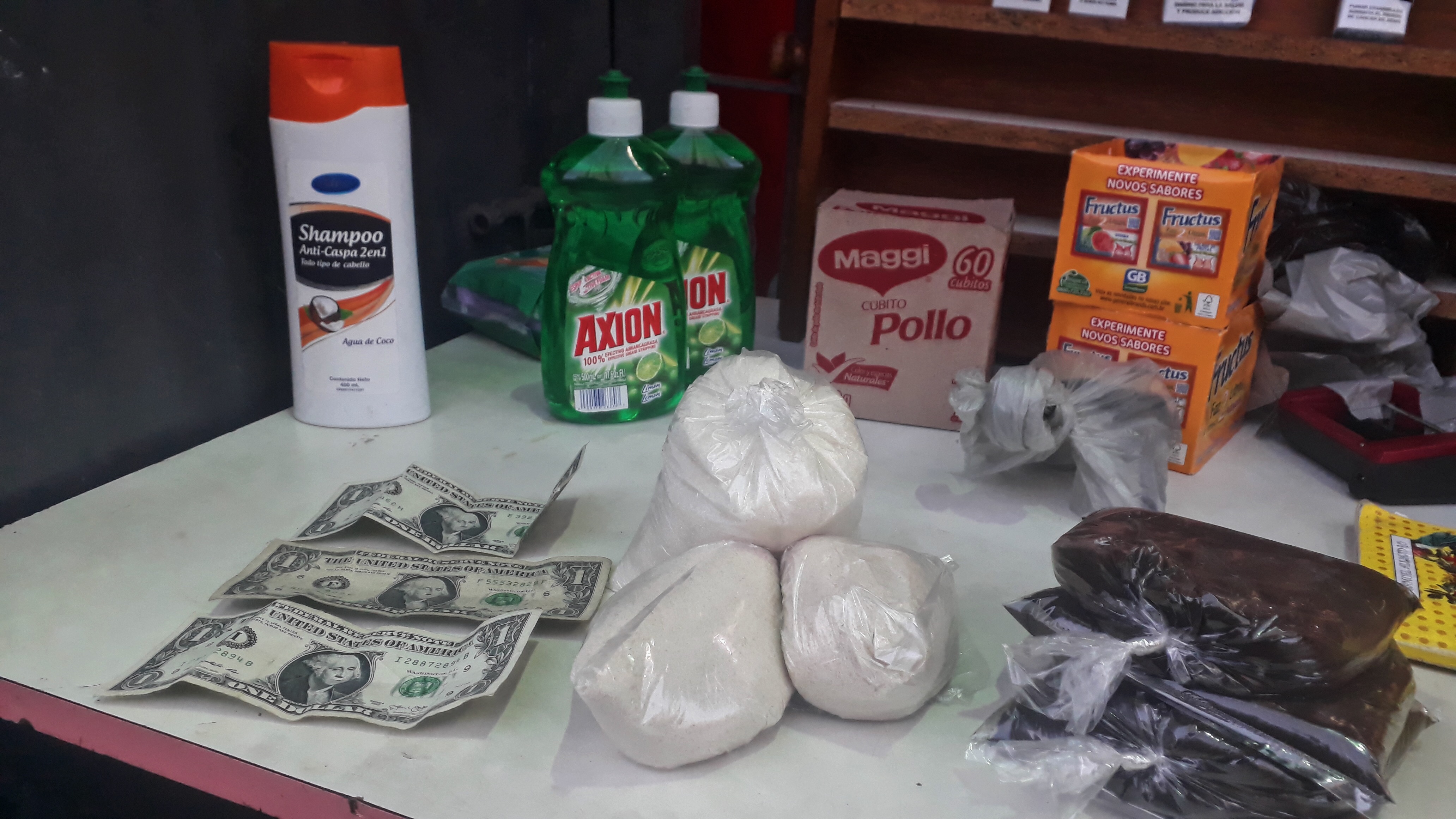

Groceries, basic goods, medicine, and even used clothes and food sold by gram are offered in dollars or bolivars, but at the day’s exchange rate. Foreign currency is now so widespread in low-income areas of Caracas that the exchange of products and services isn’t limited to U.S. dollars. Even pesos are more valuable for business owners than Venezuelan money.

Ángel Alvarado, an economist and member of the National Assembly Finance Commission, explains that those who can regularly count on U.S. dollars are usually people with jobs that pay in dollars or those who receive remittances from family members abroad: “Dollarization doesn’t exist, what’s happening on a daily basis in poor areas of Caracas and the rest of the country is that we have become tolerant to the use of foreign currency as a way to shield ourselves from hyperinflation.”

On the other end of the 23 de Enero, in the Observatorio, Iván Azuaje tends to his motorcycle repair shop until the evening. During 2018, he sold items bought in Cúcuta, but in September he realized it was no longer profitable: “Shortages are less common now, after they allowed products to be imported again, so now prices over there are pretty much the same as in here. Today, I just run my repair shop and that’s it.” He sells motorcycles, parts and maintenance and repairs, but he also confesses that very few people pay in bolivars. “It’s not even worth calculating the exchange rate.”

These changes also include spaces like private education institutions, but in Fe y Alegría’s San José de Calasanz in the 23 de Enero, the monthly fee can’t be charged in foreign currency. “Our fee is Bs.S. 10,000, less than a dollar,” explains Marisol Mendoza, headmistress and worker of the school for 25 years. “We have to survive with bolivars, and this has become a problem when we want to buy lunch for 130 students. Five of them are suffering from malnutrition. Four teachers have quit already because the salary in bolivars isn’t enough.”

In Petare, Everything Costs One Dollar

“Ten sardines for one dollar,” is what you hear under the raised bridge in Petare. Yelling his inventory at the top of his lungs is José Quintero, a hawker born in Barlovento, who parks his truck in different Caracas barrios. He sells fish between the food stalls in the Petare roundabout, where you can find all kinds of stuff, and petareños as well as people from other parts usually go and buy their groceries for a lower price. Most clients stretch out their hands with $1 bills and receive a bag filled with the product. “This is like the ‘todo a mil shops’ from back then,” you hear a lady say, jokingly, about the shops where everything cost 1000 bolivars. “But now it’s ‘everything for one dollar’”.

Most clients stretch out their hands with $1 bills and receive a bag filled with the product. “This is like the ‘todo a mil shops’ from back then. But now it’s ‘everything for one dollar’”. Photo: Génesis Carrero, Caracas, 2020.

Enrique Cisneros owns a grocery store in the La Montañita sector of Petare. The store, which he opened over 15 years ago, is almost empty. He used to even sell school supplies, but today he can only sell cheese that people in the barrio can purchase with U.S. dollars, pesos, or a point of sale for which he has to pay a monthly fee of $40. “This is the only country in the world where even the dollar loses its value, that’s why I’m about to go broke even though I get paid in greens,” explains Enrique when he tries to do the math and the result is that, on a good day, he can make $15 in sales.

In Petare, you can find preschools and schools where the monthly fee is $10. The Unidad Educativa María Teresa, located in the heart of this parish, is an example. Alma, a teacher at that school, says they made that decision in October 2019 and far from losing students, the number increased. The teacher believes it’s due to the lack of qualified staff in local public schools. “Even though this is a low-income area, a lot of people here have dollars,” she says.

Dollarization has gone so deep in petareños that they even have unique dynamics between business owners. María Cristina Solórzano owns a store in the Zona 6 of the José Félix Ribas sector and two weeks ago she decided she wouldn’t accept $1 bills anymore, because the Chinese—the local wholesalers—lowered the rate at which they accept the smaller U.S. dollar bills.

Foreign currency is now so widespread in low-income areas of Caracas that the exchange of products and services isn’t limited to U.S. dollars. Even pesos are more valuable for business owners than Venezuelan money. Photo: Génesis Carrero, Caracas, 2020.

María Cristina receives more dollars than bolivars even though she has all the payment options to pay in bolivars available. People buy cocuy liquor, anise liquor, spirits, and other alcoholic beverages with American currency. They also buy candles, bread, plantains or corn flour and, to round out the final purchase, they include pencils, sheets of cardboard, or glue. She manages to bring in $50 on a good day, but she explains that it’s not much what she can profit or save, because the business is consumed by the product’s prices; she gives an example: “I go to Catia to buy Fructus (a powdered soft drink), and two weeks ago the box was B.sS. 95,000, believing I would buy more because I sell in dollars. Turns out, I bring in less now because the box is Bs.S. 135,000, so I had to use the profit.”

Juan, a baker for more than 20 years in La Bombilla, Petare, isn’t afraid of thieves looking for dollars: “If they want to steal, they go to butcher shops, or supermarkets in Prados del Este that make up to $1,000 a day. They don’t come here to steal what the people from el barrio give us.”

Those Without It

Although you can see foreign currency all over the place, a big chunk of the population, such as those working for the state, still get paid in bolivars. “Dollarization doesn’t mean that the Venezuelan economy is going to jumpstart again,” Ángel Alvarado points out. “Those living in bolivars are using a currency that excludes them from productive economic circuits and are subject to an impoverishing inflation.”

Jeanelly Quintero’s life fits that description perfectly, a 38-year-old woman with five young children she has to feed. Her monthly wage of Bs.S. 300,000 as a chambermaid at a hospital is all of her income. “I’ve never even held anything larger than a $1 bill, and that was because I found it on the street,” the woman says, as she waits at the subway station in Petare for a friend who promised her some groceries. All she can afford with her salary is half a carton of eggs, one bag of corn dough, and a few vegetables.

Groceries, basic goods, medicine, and even used clothes and food sold by gram are offered in dollars or bolivars, but at the day’s exchange rate. Photo: Génesis Carrero, Caracas, 2020.

Her story contrasts with that of Stefany Aloisio, a young vendor in Zona 1 of the José Felix Ribas area, who claims that selling the basic needs products, even those from CLAP boxes, has been her way of saving some money and splurge a bit—as she did, throwing a party for her daughter’s first birthday. She saved for six months and spent her profits: $350.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate