The Five-Year-Transformation of the National Assembly

2020 might be the stage for new parliamentary elections in which chavismo expects to revert the effects of MUD’s 2015 victory. In the meanwhile, harassment and coercion have scraped off the opposition majority.

Photo: DW, retrieved.

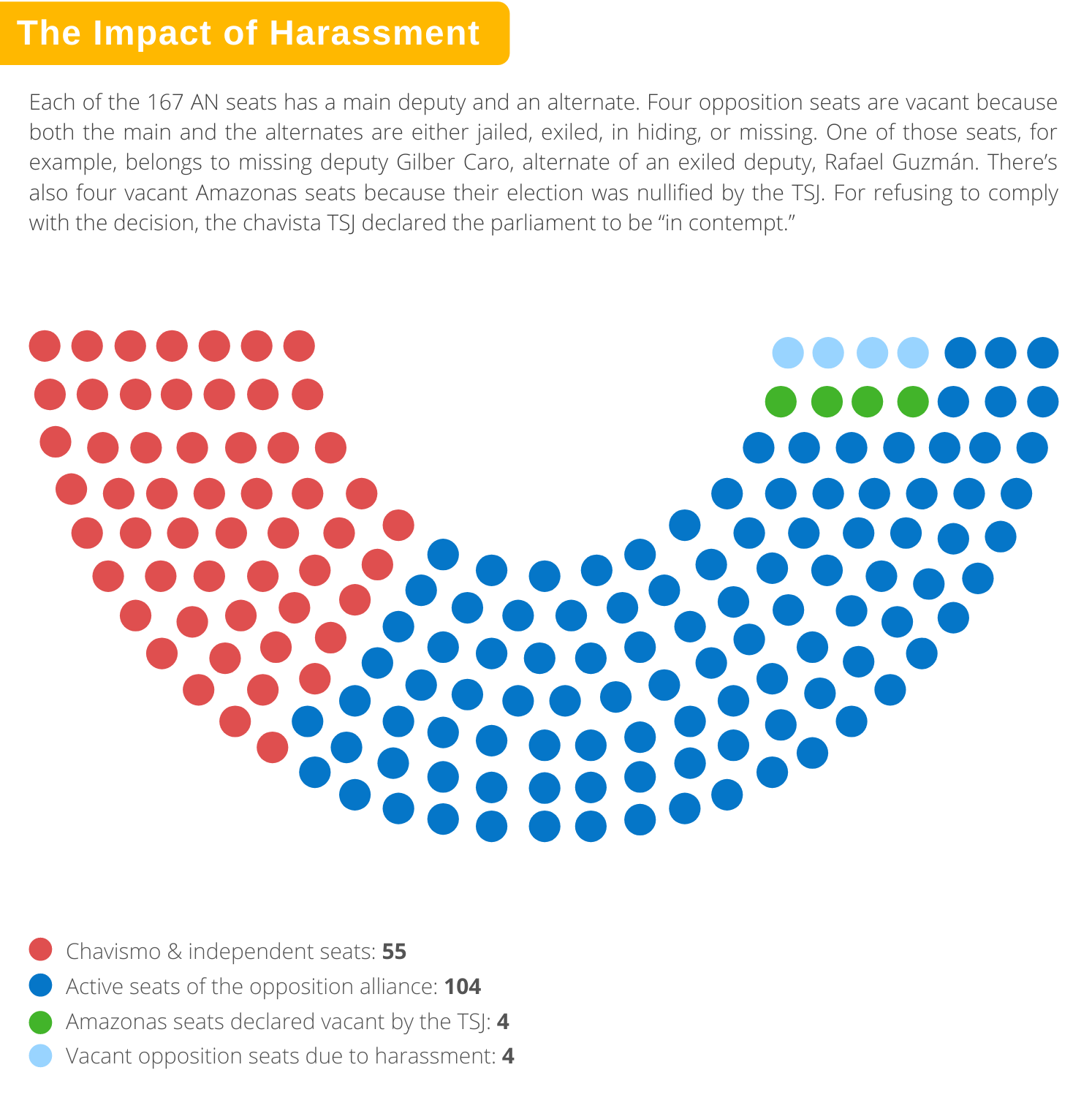

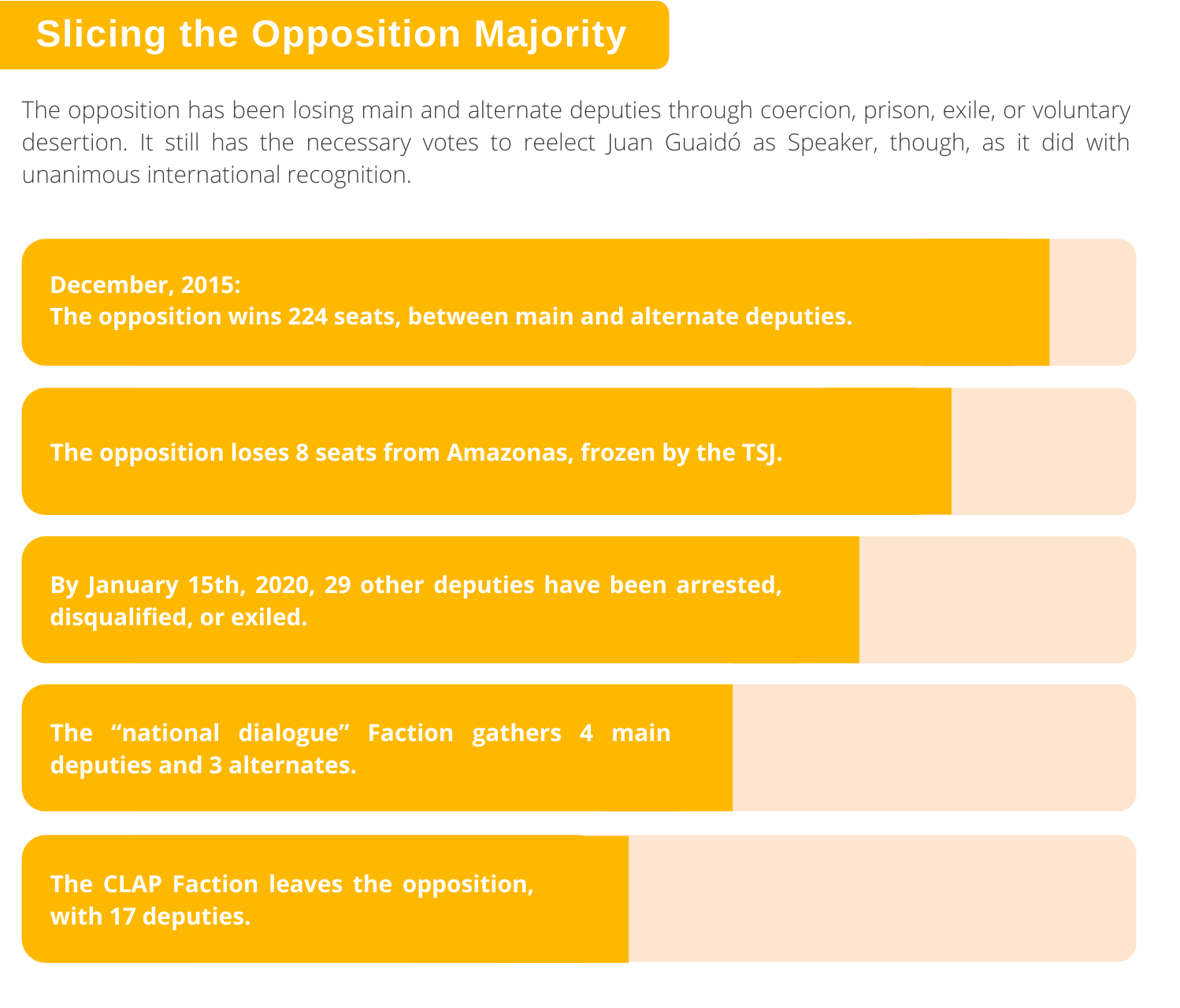

As the only body representing Venezuela’s Legislative Power by Constitutional mandate, the National Assembly is composed of 167 main deputies, each one with an alternate deputy. For the legislative elections of 2015, all the opposition parties joined the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), and they won the absolute majority of the National Assembly: 112 seats. The remaining 55 were allocated between chavismo and independent deputies (those without parties).

This configuration changed during the 2016-2020 period because of judiciary harassment or coercion from Nicolás Maduro’s regime. Right now, 24 deputies are in exile (between principals and alternates). One is missing, three are jailed for political reasons, three have been “disqualified” by the illegitimate national constituent assembly (ANC), and four Amazonas deputies were scratched by the Tribunal Supreme of Justice before they could take their seats. 33 legislators —and their constituents— have seen their political rights violated, mainly through mechanisms such as the elimination of parliamentary immunity by order of the ANC, and criminal accusations by the TSJ (like the case of deputy Juan Requesens, who was thrown in jail by chavismo because of his alleged involvement Maduro’s drone assassination attempt).

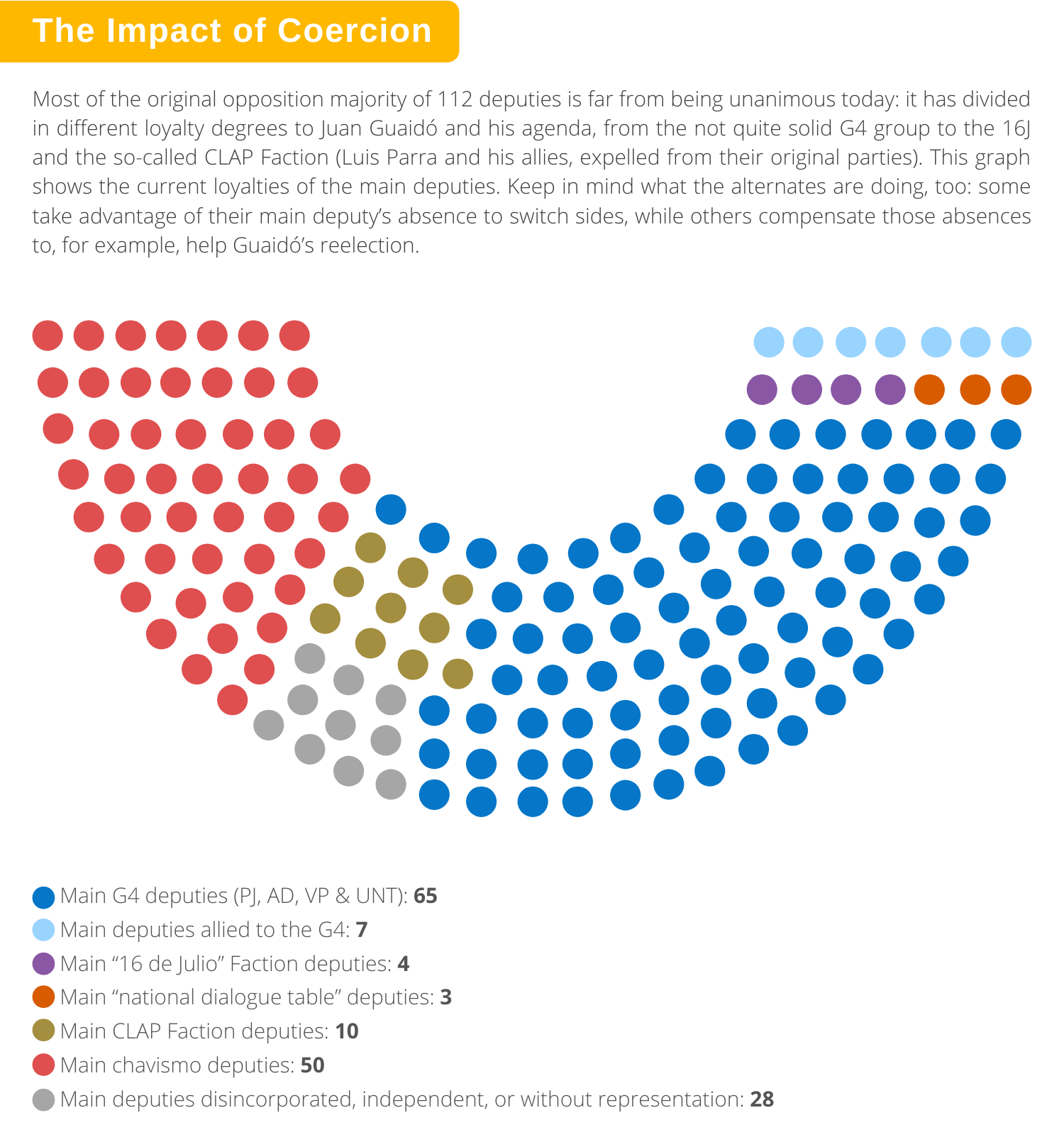

More recently, the majority achieved by the opposition in the 2015 parliamentary elections has been diminishing through the recruitment of deputies who arrived at the AN as opposition, and now favor the interests of chavismo. Such is the case of Luis Parra’s appointment as AN Speaker, with support from the PSUV, and from a group of the so-called “national dialogue roundtable.”

They all claim to stand against the “hegemony of the G4,” a faction formed by the four main opposition parties. Together, those parties (Acción Democráctica, Primero Justicia, Voluntad Popular, and Un Nuevo Tiempo) have more deputies at the AN than any other organization. This is different, mind you, from the “16 de Julio” Faction, which also resists the G4 agenda, but can’t be considered a part of the fake opposition.

The mix of all these factors, along with the economic (and ethical) frailty of deputies who earn no wage and the historical pull towards division on the opposition camp (accentuated by each failure to remove Maduro from power), have sliced away, bit by bit, that promising majority that the opposition earned on the now remote December of 2015.

All parliaments depend on vote counts: those necessary to appoint its authorities, regulate other branches of public power, approve laws, and so on. In the case of Venezuela’s National Assembly, harassed by an entity that is trying to replace it (the ANC) and the TSJ, and now without access to its own premises, these graphs are meant to help you understand how the regime has been reducing the opposition’s capacity to appoint its own authorities, or new Electoral Council authorities, or approve much needed credits for the state.

And they also confirm the value that the dictatorship still sees in the National Assembly, because why else would it want to control it? This means the regime will do whatever it can to recover it through actual parliamentary elections… or by force.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate