A Miracle of Music and Hard Currency

Last weekend, caraqueños enjoyed CúsicaFest, a two-day music festival with three generations of Venezuelan bands. It was a triumph of organization, frank capitalism and nothing but joy for those who could join the crowd.

Photos: Maria Josefa Maya and Victor Drax

“You know, this is the perfect bubble snapshot,” says Mafer, and it’s hard to disagree.

It’s December 15th, the second day of the CúsicaFest, and the afternoon is slowly mutating into the evening. Caraqueña band Viniloversus is about to play on the main and only stage, and we just saw Anakena and Malanga, the former from our latest generation of successful musicians, the latter, a classic Venezuelan act. Right now, the air smells of grass and vanilla. We take advantage of this pause to stand on a hill on the side, after a pee break, and we just draw in the atmosphere, kinda floating in a haze of disbelief. This kind of stuff isn’t supposed to happen in today’s Venezuela.

Remember: hyperinflation & post-apocalypse depression. Diseases long conquered by mankind are appearing again in a nation with an already dire health crisis. Our diaspora deals with xenophobia and those of us still here survive amidst chaotic uncertainty. Out of the freaking blue, Cúsica, a Caracas nightclub, announces the CúsicaFest, a two-day festival with the cream of the crop in three generations of Venezuelan rock. These are Grammy-nominated artists, people known for making some of the best music this last decade in the whole region. Venezuela is going through a de facto dollarization and a lot of our reality is experimental, so what can you expect from Cúsica’s bet at a time like this?

A festival like this wouldn’t have been possible last June. Photo: Victor Drax, 2019.

Surrounded by food trucks and concertgoers, we’re shocked.

Maybe it’s the crowd itself; everyone’s on their best behavior. Nobody’s getting shitfaced drunk, nobody’s looking for a fight, nobody’s being obnoxiously loud. Beers and rum are sold at different booths, and this would normally mean long lines of shirtless dudes with a chip on the shoulder. Instead, this might as well be a picture from Coachella. Everyone’s being civil, focused on enjoying themselves. Fellas are dressed as if going on a camping trip, tiny crowds are singing and laughing, girls pose with their friends for selfies.

Or maybe it’s the top-notch organization. We just come from what may be the classiest pee break we’ve ever had; it was a clearly-cut line with a crew of guys at the end coordinating the flow of people like it’s a high-risk oil-drilling operation. They seemed to know which porta-potties were available at all times (a segment for guys, another for girls—including toilet paper), so you go in, do your business, walk out and there’s a lady with hand sanitizer. I’ve never felt this loved before.

And that bathroom trip is the perfect example of how everything flows during the festival. I cannot stress enough how well organized this thing is; whenever you attend a concert around here, there’s an expected level of suckage that you just have to put up with. Lines in venues are usually a form of torture, waiting from half to several hours, and nothing is more fun than reaching the ticket booth to find that someone messed up and there’s a problem with admissions. Here, you parked at a nearby mall in El Hatillo, eastern Caracas, and a shuttle would take you on a three-minute drive to this field. There was no tortuous line because a big team was handling arrivals. You show up, get your concert bracelet, security frisks you thoroughly, and in you go. Easy-peasy.

But Mafer is right: a festival like this wouldn’t have been possible last June. I don’t know if you’re in the loop, but a little over a month ago there was a free rap show in a famous Caracas park (Parque del Este, if you’re wondering) and it was an unmitigated disaster with injured kids and at least one confirmed death. It was a super horrid omen of what we could find, but the CúsicaFest was in another dimension that you could only access in our new dollarized reality. I don’t mean that as criticism. Having dollars flowing freely through our economy means that the money you have in your pocket is worth something again, and just that mere fact feels like getting a kiss from the one you love, after years of watching your money turn into sand between your fingers. What you experience here is just the way things are in Venezuela today. There are booths selling t-shirts at $25 (you know, the normal price for a t-shirt) and a stand has Arizona Iced Tea and Jolly Ranchers like you’re at a festival in, I don’t know, Portland.

Nobody’s making a fuss over prices because this scene isn’t exclusive of the festival. Granted: there’s a barrier of entry into the bubble (having access to hard currency), but those fortunate enough to cross it are having a good time because this is the new normal, and maybe that’s the very reason why everything turned out so well. It’s all paid in greens, dollars that more and more Venezuelans now have access to.

About twenty minutes into our sociological contemplation, Viniloversus takes the stage and one of the first things frontman Rodrigo Gonsalves says is “Goddamn it, it feels good to play in Caracas again!”

The day was swell, relaxed, harmonious. Photo: Victor Drax, 2019.

And that’s the other thing. Most of these bands embody our transitory Venezuela. They’re folks with established careers here, commanding huge followings, and they left for pretty much the same reasons everyone else did. Los Mesoneros hadn’t played a show in Venezuela in four years (and they rocked the house after Vinilo). Ari Barbella, Malanga’s frontman, choked up on stage midway through their show: “You guys have no idea of how good it feels to see you all here.”

“I don’t wanna get nostalgic now,” says Rodrigo between songs. “Because there’s no time like the present. We’re alive, we’re breathing and as long as it’s so, we can tackle any problem. This event is evidence that good, quality things can still be done in Venezuela.”

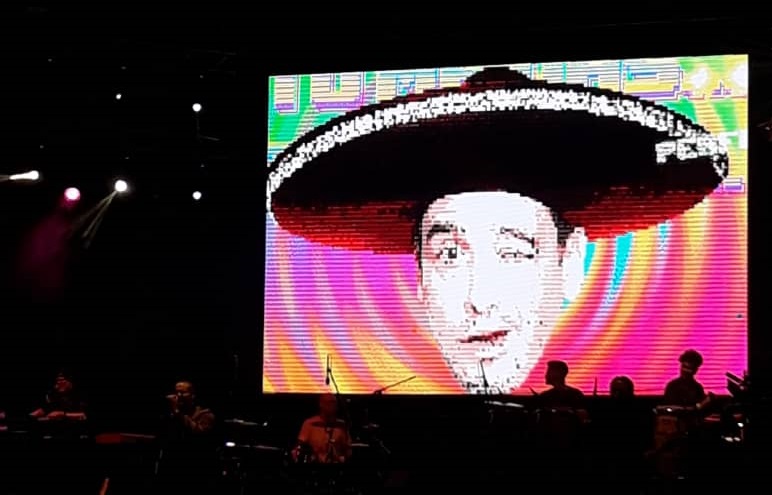

Los Amigos Invisibles played after Los Mesoneros, and owned the night with over 80 minutes of delicious funk, salsa and the new sound of the Venezuelan gozadera. A gazillion people singing and dancing and laughing, like they did with La Fleur, La Vida Boheme, Tomates Fritos and Desorden Público the day before.

The day was swell, relaxed, harmonious. We’re people (and I’m including everyone, from promoters to artists) who have suffered bitter political misadventures and are now desperate for a simple good time. For those of us in the crowd, it was a night where things felt possible, on a year that began with this horrendous, oppressive blackout and it’s now closing with a storm of color and joy. This weekend, we weren’t just surviving. We were actually living.

“Tomorrow we’re back in the fray,” Mafer sighed on the way home, her eyes shining. “Back to water shortages, the stupid prices at the market and this fucking car needing an overhaul. But Jesus Christ, we needed this so bad.”

And, as the cliché goes, that’s something that money can’t buy.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate