What Is Happening in Venezuela’s Protected Capital?

Are things better in Caracas? New business has sprouted, traffic jams are back, people are getting ready for Christmas, and no one talks about politics. Here’s a stab at understanding what’s going on.

Photos: Raul Stolk

As Fantine faded under a ray of light with Jean Valjean at her side —after promising to take care of her beloved Cosette, the crowd at the Ríos Reina hall of the Teresa Carreño theater roared with amazement. It was perfect.

There was only one thing out of place: the heat.

It wasn’t too bad, though, just enough to remind you that this was not the Lincoln Center. Fixing the air conditioning system of Venezuela’s most important theater hall is well into seven figures. An amount that escapes the interest and possibilities of the authorities in charge. Having the audience seat through three hours of a Broadway-quality show, in the hellish heat public employees must endure in government acts in the same venue, was not the kind of experience the producers were aiming for. So they rented a cooling system at a very high price that would allow the teary eyes of the audience to stay moist.

This is a good example of what can be seen in the streets of Caracas these days: a strong presence of the private sector and the complete absence of the state. It’s complicated and hard to explain. So complicated that media and analysts dedicated to covering and explaining Venezuela haven’t been able to do so (including us, of course).

Here’s a stab at understanding what’s going on. Some names below have been changed to protect the innocent.

At first sight

One year ago, when there was no Juan Guaidó and no end of usurpation in sight, there was almost no one in Caracas that didn’t have plans to leave the country. Leaving Venezuela was THE conversation at every single level of the socioeconomic food chain. And, of course, after the March blackout, many who didn’t even have formal plans in place simply took off.

Returning to Caracas one year later feels like going back to a bombing site and finding people rearranging the rubble to make their lives around it.

Many traditional businesses couldn’t survive the blackouts and the hyperinflation. Rising costs and a controlled economy are a deadly combination. In a corner at Los Dos Caminos there used to be an arepera for years. In that same building there was the Dolomiti ice cream parlor. A couple of businesses that had become landmarks. Now both are closed. They just couldn’t stay afloat during the crisis. But between the two closed shops, there’s a brand new cocada place (a traditional coconut shake that has become weirdly popular lately) with a fresh new sign. These new flashy businesses are sprouting all over east Caracas.

Returning to Caracas one year later feels like going back to a bombing site and finding people rearranging the rubble to make their lives around it. Photo: Raul Stolk.

Transactional dollarization is the talk of the town, of course. It’s shocking to see cash transactions in the street. It’s more common to see cash dollars than bolivars. The bolivar bill disappeared, though people make many transactions in the local currency. And if you have bolivars in cash, they are at least 40% more valuable than a transfer. Even when the high prices have most people struggling, there is a general sense of security in dealing in a currency that actually has some value.

Rush hour is back. For years, Caracas, a city that used to be packed with cars, suddenly found its streets and highways empty. A clear symptom of the crisis. Some folks in Caracas even look relieved with the return of traffic jams, and many explain it by assuming it’s due to internal migration: people from Maracaibo, Barquisimeto, and Mérida have moved to Caracas because it’s the only city with (partially) running water, electricity, and internet. Others say it’s migrants returning to the country; every migration wave has its backwash, and the one after the March blackouts was huge. But there’s also the return of replacement parts to the local market. Many cars in Caracas were parked because there were no parts to fix them. But now, door to door services are importing everything, from pistachio oreos to alternators for a ‘92 Corolla.

Nothing that is happening right now in Venezuela has one simple explanation.

An informal reform

Lawyers are usually a good thermometer of how the market is. But right now that thermometer is not easy to read. Luis, the managing partner of one of the largest law firms in Caracas, says they haven’t seen a spike in work that would reflect the activity that can be seen in the street. “The explanation,” he says, “has to do with the fact that almost nothing is being done through regular channels. And this, for now, has most of our regular clients, which are large transnational companies subject to international regulation and standards, sort of waiting to see where this is going.” For them, having Maduro go on TV and saying that dollarization helps release the pressure of hyperinflation is not enough to generate security.

The story of the local investor is quite different. The regime got out of the way—although it’s still there. That’s the extent of Maduro’s “economic reform.” They are not enforcing price regulation and foreign exchange controls, the tax administration is not harassing businesses, they are letting imports in, and our very stringent labor law has been thrown to the backburner. Many employers just pay a small portion in bolivars used for payroll purposes (and only those interested in saving face) to calculate labor benefits. The rest is paid off the books, or at least on parallel books.

And how is it paid? In some instances with cash, and through Zelle or Paypal transfers for those lucky enough to have a foreign bank account. Others just receive the payment in Bolivars indirectly at the latest dollar street rate.

When workers hear about things like the “minimum wage,” they laugh and feel relieved that they don’t have to pay attention to it anymore. Unless you are a public employee, of course. Minimum wage is only used to pay pensions and government workers. See, at some point the regime realized that having a huge payroll to keep allegiances wasn’t as useful as it used to be. Government workers, including those in PDVSA, are subject to massive cuts in their labor benefits, even those obtained through unionized contracts. Today, most of them don’t even have insurance.

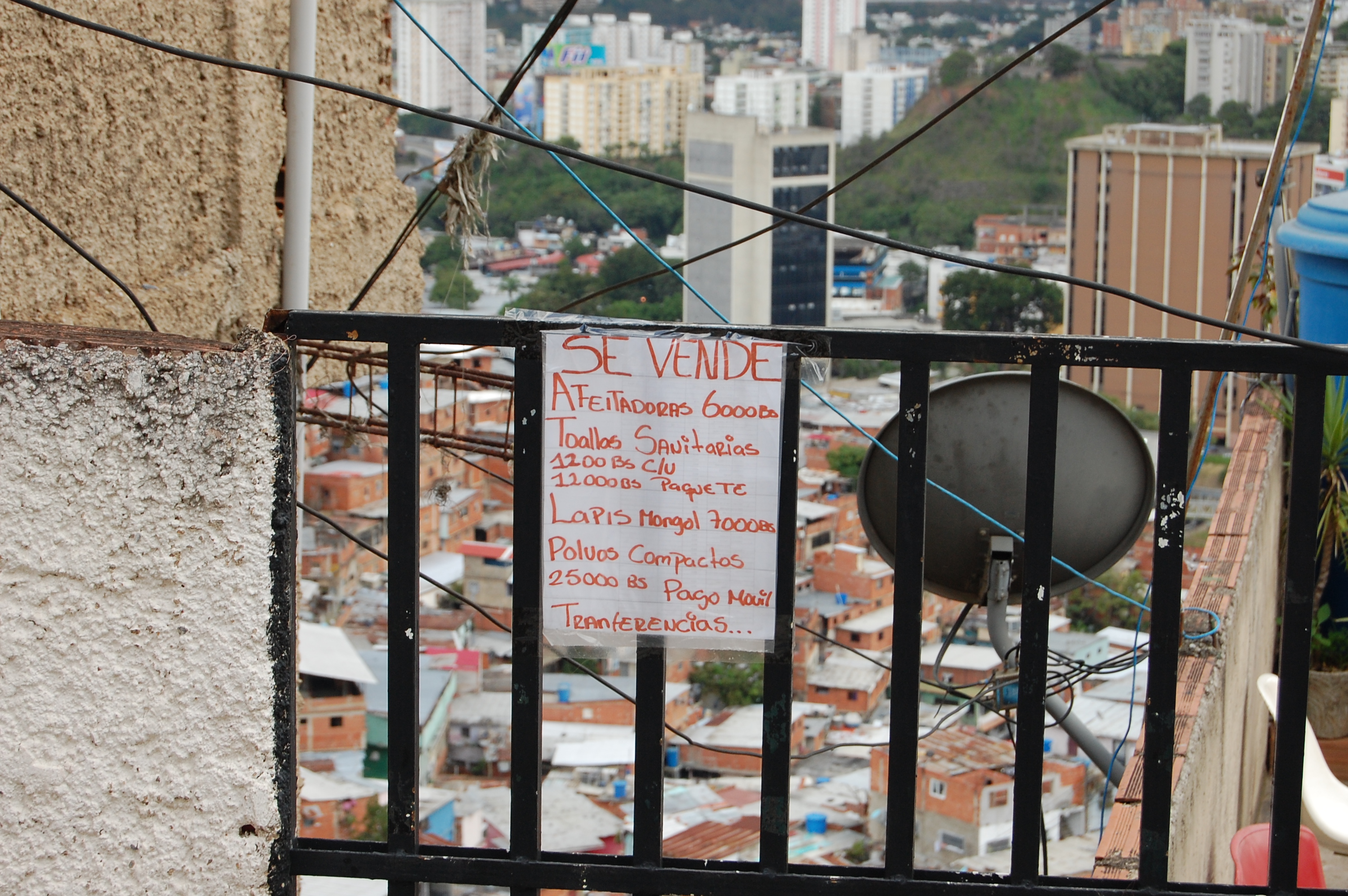

Even though informal commerce has always been present in barrios, it now appears that most homes sell whatever they can in order to make ends meet. Photo: Raul Stolk.

The CEO of a traditional company in the energy industry explained that they had reduced payroll from 400 to 10 because they were producing squat and the government and unions were driving them crazy. It was a long and painful process. But in the end, they just kept key personnel, and they hire per contract depending on the workload.

But this informal reform hangs on the very delicate balance of fiction and reality. The regime got out of the way, but it is still there. There is no security, and no guarantees that the government will remain wherever it is right now.

What about the Barrios

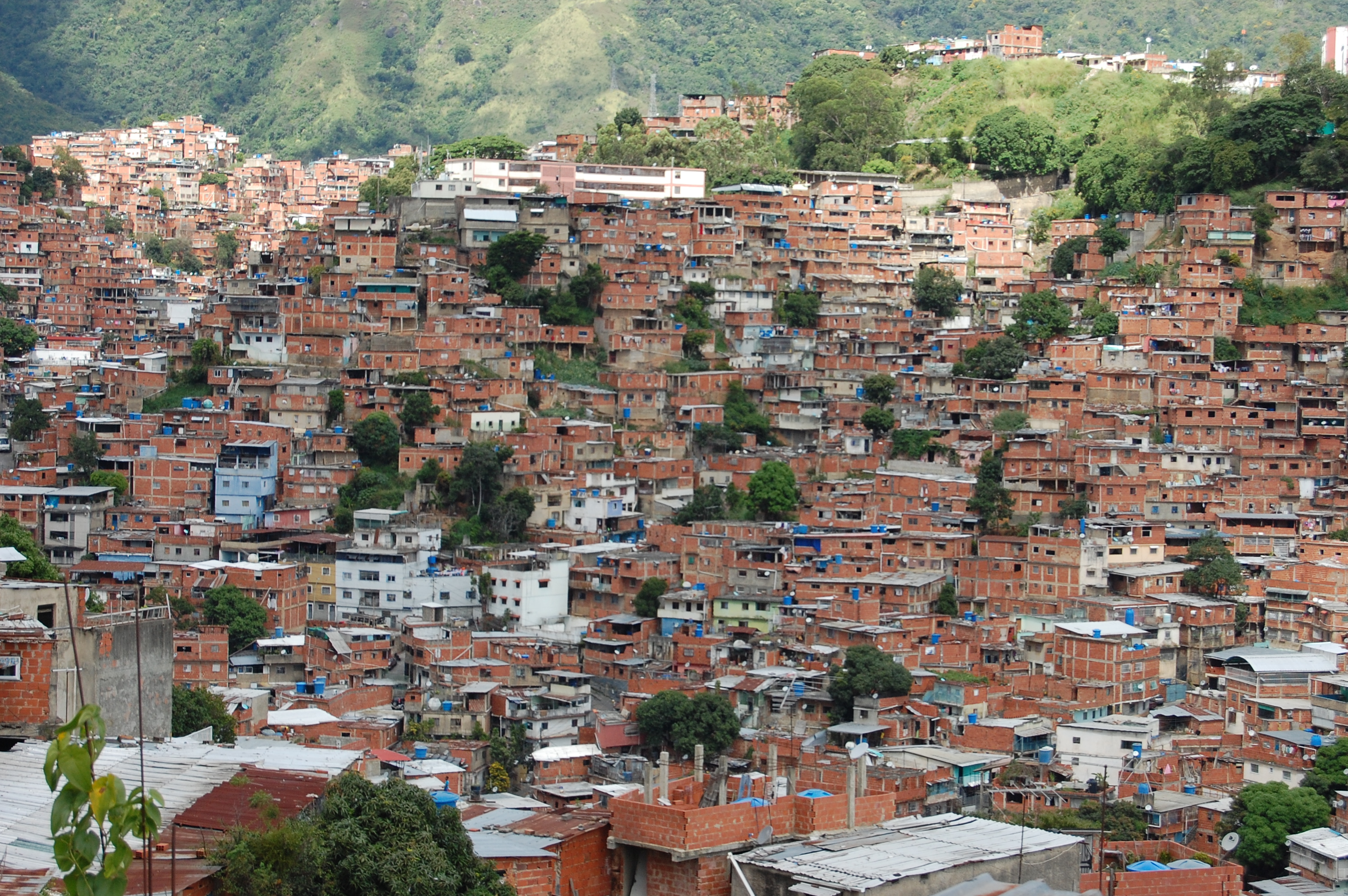

Petare is the largest slum in Latin America, it harbors twice the population of Iceland. Photo: Raul Stolk.

While Florantonia Singer and Laura Castillo start explaining the dynamics of power in La Cruz, a small barrio at a privileged spot in east Caracas, they are swarmed by a group of children in school uniforms. “These kids are part of the first cohort of our La Cruz TV project, where we give tools to the community, including children, to become reporters of daily life in the barrio,” says Castillo. La Cruz TV is a spinoff of their award winning El Bus TV project, where they have journalists telling the news in person on buses all over the country.

La Cruz is a good place to experiment with projects such as these. It’s dead smack in the middle of Chacao, a safe neighborhood, and it’s packed with people. Although it’s only a few blocks wide, 5,000 people live there. It’s mostly rooms for rent since the barrio is near a commercial area. Most of the people who take rooms there work nearby, from cooks to security personnel to accountants. But La Cruz itself has a lively economy within. You can find English classes, beauty parlors, and very decent hamburgers. Most of those businesses accept dollars, of course. Part of the project La Cruz TV and the architects at CCS City 450 are trying to develop includes opening the barrio to the rest of the city by showing what La Cruz offers and bringing visitors in.

Most of the people of La Cruz are focused on working jobs that can get them dollars, and when you ask them about politics they just laugh. “A few days ago Héctor Rodríguez, the governor of Miranda, came by with a bunch of his people to make some announcements,” says Marielly, a woman who was introduced as a leader of the community. “And you want to know what he announced? He said they were going to give 20 million bolivares to La Cruz. You know how much that is? It’s 800 dollars! What are we going to do with 800 dollars?”, she laughed.

The infamous blue water tanks. Photo: Raul Stolk.

Barrio politics on the eastern rim of Caracas are more nuanced. Petare is the largest slum in Latin America, it harbors twice the population of Iceland. Andrés Schloeter is well known there. He used to be a councilman when the opposition held the stewardship of Sucre, and he was lined up to run for the mayor’s office—until the opposition decided not to participate since the process was not reliable. Walking through old Petare with him feels like a campaign spot: old people approach him, he knows everyone’s name, a kid comes up to him and calls him by his nickname “Chola,” and a football gets into the shot and he kicks it back to some children playing in the plaza.

Schloeter is currently in charge of the Alimenta la Solidaridad project in Petare. Alimenta is an NGO which feeds 3,000 children in Petare alone through 33 comedores, and 12,000 nationwide. The interesting thing about this project is that a big part of its success depends on the community. The food is prepared by the mothers, who are organized and trained by the Alimenta la Solidaridad staff. The community also selects the children. Schloeter says they are very conscious of who needs to join the program. Another interesting thing about the program is that Alimenta ensures that all the children who are admitted into the program must attend school.

Irma, one of the mothers who prepare the food in the 19 de Abril comedor (which caters 40 children), says two of her kids are in Perú and the third one is getting ready to leave. Her eldest is a doctor who was able to get a job in a hospital and sends her around $20 dollars per month. “But that doesn’t buy much these days, not like before.” Irma’s case repeats across the board with those families who used to depend on remittances. Those who left send the same amount of money they used to, but those 20 bucks don’t help as much now. Plus, they only receive Clap boxes once every two months in Petare, and they don’t even include protein. They don’t count on it anymore.

But there are ways to go around the crisis. You can see signs on every other door selling goods or offering services. From ice and snow cones to maxi pads (individual or full pack) to beans, matches and shampoo.

Alimenta is an NGO which feeds 3,000 children in Petare alone through 33 comedores, and 12,000 nationwide. Photo: Raul Stolk.

Dealing with the energy and water cuts has also become a form of service. The 19 de Abril only gets water once a week on Thursdays, but it only reaches the lower sections of the barrio. Before disappearing, the government distributed plastic water tanks when they realized this was not a problem that would go away soon. Those blue water tanks can be seen on the tin roof of almost every single house in Petare. Some folks carry the water to the top, others pump it with improvised electric pumps (which ultimately mess with the water pressure of the regular system). These services are usually not charged in Barrios, but they have to pay for the workaround—which sometimes is more expensive than what they would pay if the service was properly charged.

Petare politics these days are different to how they used to be. Politicians are ever absent, and the only presence of the state can be felt in the FAES fortress at the foot of the Petare market. Schloeter said that Jose Vicente Rangel’s chavista government doesn’t mess with them. The program is very important for the community. “A few days ago,” he says, “I was showing the comedores to a group of foreign journalists and we were stopped by ten gang members with high caliber weapons and machine guns. I tried to play it cool, but deep down I thought this was it. But once they learned I was in charge of the comedores they radioed their superiors and they let us go”.

FAES, Maduro’s death squads, in their fort at the foot of Petare.

Caracas is Caracas, the rest is condemned

Imagine how many problems you could solve if you could snap your fingers and disappear half the population of a country in crisis. Of course, this idea could only exist in the head of a fictional megalomaniacal villain —and chavismo.

Yes, Maduro is pulling a Thanos.

A big chunk of Venezuela’s public spending comes from formal and informal subsidies. Clap boxes, water and electricity, housing, plus an inflated public payroll. For Maduro’s government, 5 million migrants (and the prospect of turning into 8 million in 2020) must sound like a blessing. This explains why the state moves so slowly on dealing with the electric grid, the problems with water supply, and the health crisis.

Letting the rest of the country wither and die is state policy, it’s a decision. While the sensation of visiting Caracas may leave a trace of hope, the knowledge of the cost has a heavy stench. One of the big questions about chavismo was how far was it willing to go for self-preservation; well, we got our answer.

While social media roars with outrage and indignation over the political crisis, many people on the ground have turned the page. And this is not necessarily a good thing, nor a bad one, it just is. This is the general mood everywhere, folks just got tired of waiting for the government to solve their problems or praying for a miracle from the opposition. No one is thinking about the sanctions or where the heck is Maduro right now: Giving away the oil industry to its foreign allies? Illegally extracting gold? No one cares.

For now, whatever hope there is for normality, hangs in the private sector’s arms.

It was the last night Les Miserables would be playing in Caracas, for now. The newly formed Venezuelan theater company hopes to take the show abroad to Panama and Colombia. After the curtains closed and the players took a bow, the whole production team accompanied them in singing “Do you hear the people sing” one last time, along with the full Mariscal de Ayacucho Orchestra directed by Elisa Vegas.

It was invigorating. It was perfect. More than perfect, perhaps. As the show gave the audience something more than the promise of a revolution, it gave them a glimpse of how things could be.

“When the beating of your heart/Echoes the beating of the drums/There is a life about to start/When tomorrow comes” Photo: Raúl Stolk

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate