The Day the Frogs Stop Singing

A fungus is annihilating batrachians all over the globe, including those that make Venezuelan evenings sweeter with their song. In our country the drama only gets worse because it’s almost impossible to research and protect.

Photo: Aldemar Acevedo / University of California retrieved

After a decade of monitoring the remaining population of striped toads in the center of Venezuela (Atelopus cruciger) the team from the Instituo Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (IVIC) had to stop their work in 2015. External funding ran out and crime in the Mario Briceño Iragorry municipality made it impossible for field work to continue.

Scientists had determined that these batrachians, once distributed from Bejuma (Carabobo) to Cerro Azul (Cojedes) only had three sanctuaries left: Guatopo, Cata, and Cuyagua, from where the IVIC was now pulling away.

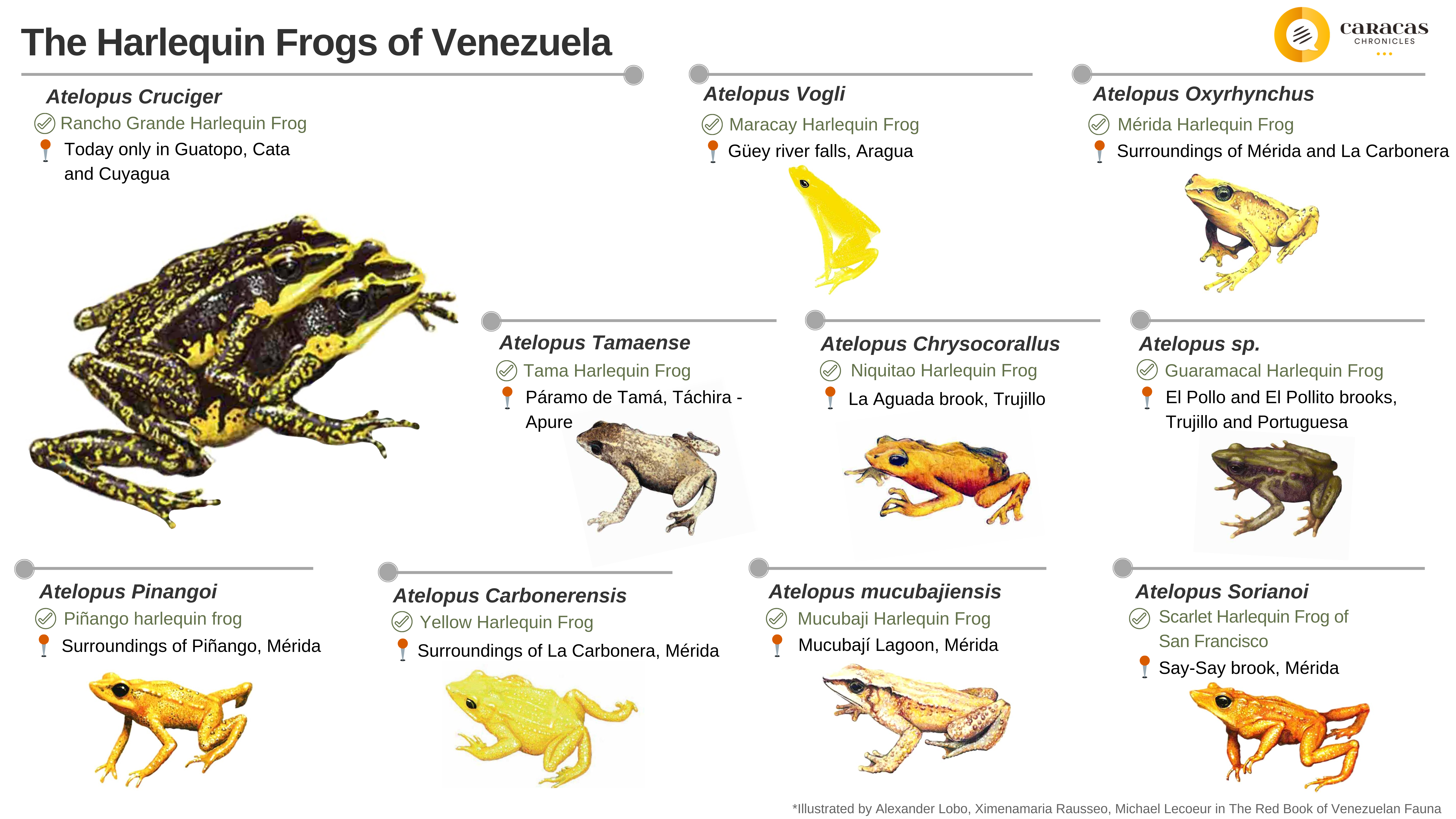

Up until the ’80s, ten species of the Atelopus genre existed in Venezuela. Today, Atelopus cruciger is the only one left.

Scattered between the Andes and the Coastal mountain range, these little harlequin toads were so abundant that back in the ’70s it was common to see dozens of small yellow frogs in La Carbonera (Atelopus carbonerensis) flattened and dry on the road between Merida and La Azulita. Then, they vanished. In 1991, a single specimen was impossible to find, and this happened with the rest of the Atelopus as well.

Scattered between the Andes and the Coastal mountain range, these little harlequin toads were so abundant that back in the ’70s it was common to see dozens of small yellow frogs in La Carbonera (Atelopus carbonerensis) flattened and dry on the road between Merida and La Azulita. Then, they vanished. In 1991, a single specimen was impossible to find, and this happened with the rest of the Atelopus as well.

Why were there just a handful of Atelopus cruciger populations rediscovered in the 2000s and only one solitary female specimen of the harlequin toad of Mucubají (Atelopus mucubajiensis) in 2004? What annihilated the Venezuelan species of harlequin toads?

It was the same thing that happened in every country where frogs died en masse: a disease caused by the chytridium fungus or BD (Batrachochytium dendrobatidis), chytridiomycosis, sprung from out of nowhere.

The Korean War Is to Blame

The plague by the chytridium fungus in Venezuela isn’t unique: the whole planet is running out of amphibians. BD has spread all over the highlands in South and Central America. It has devastated entire populations in Costa Rica, Panama and the Caribbean. It has been found in Italy, Switzerland, Spain and France, as well as in parts of the U.S. From Australia it made its way to New Zealand and Tasmania. Some species as common as the Mount Glorious day frog (Taudactylus diurnus), once the most frequent in its region, have completely disappeared. The epidemic seems to be unstoppable.

At least seventeen species of Venezuelan amphibians are infected with BD, according to herpetologists like Margarita Lampo and Celsa Señaris.

This loss of biodiversity is massive; practically every herpetologist working in the field has witnessed the sudden disappearance of an entire species in the last thirty years. Today, amphibians—predating dinosaurs and among the oldest families of living creatures—are considered the most threatened animal on planet Earth: their extinction rate is between 40 and 45 thousand times higher than the background rate, which is the average rate at which a class of animals becomes extinct during ordinary geological time periods. In the case of amphibians, it’s estimated that a species should become extinct every thousand years. A third of the species of this entire class, 1,900 amphibian species, could disappear.

There’s no cure for BD yet, and it stays alive for a very long time without a host. The fungus can also move autonomously as spores through bodies of water.

How did such a lethal fungus reached so many corners of the Earth so quickly? Human traffic. It was previously thought that the fungus spread through mass transportation of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) but a 2018 study showed that the BD originated in East Asia and became globalized through mass human migration during the Korean war. Afterwards, the fungus—living in harmony with Korean species—continued to move thanks to amphibians being trafficked as either pets or food.

For example, it is thought that the traffic of the bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeiamus) from North America—immune to BD and wanted for its legs—has served as an important carrier for the fungus. In fact, several biologists have proven the presence of invasive bullfrogs in areas where the Venezuelan harlequin toads used to inhabit.

A Shift in Balance

The future for Venezuelan amphibians looks bleak. The presence of the chytridium fungus has been confirmed in the Coastal mountain range, as well as the Andes, but it hasn’t been established in the Guayana plateau, in spite of high amphibian death rates in the Auyantepui and the Chimantá massif in the ’80s.

At least seventeen species of Venezuelan amphibians are infected with BD, according to herpetologists like Margarita Lampo and Celsa Señaris. This number includes both immune species and extinct species, but it doesn’t include those decimated in the last few decades, suspected to be victims of chytridiomycosis, such as the Avila crystal frog (Hyalinobatrachium guairarepanensis) or the Caracas rain frog (Pristimantis bicumulus).

The only Atelopus left in Venezuela has a dire prognosis. While the pathogen is present in striped toads from the center of Venezuela, the high reproduction rates and specimen replacement creates a balance that counters the lethality (symptoms appear in much slower rate in low and warmer land).

However, because of climate change, the dry season gets drier—which is when the striped toads reproduce—resulting in a population increase that would allow a higher BD transmission, creating new epidemics that could be catastrophic for the species. With longer dry periods, more specimens would be infected by the fungus, a critical mass that could increase the spread of the disease.

To make things worse, in 2018 a study proved the hybridization of BD with local fungi from Brazil and Africa, so new combinations have risen that could mean a global amphibian devastation.

Research Against All Odds

In spite of the frailty of the species and their sudden decrease in distribution, Venezuela doesn’t have striped toad specimens in captivity, while Ecuador and Panama have established disinfected labs to protect their remaining Atelopus species and other genres affected by BD. A decade ago, when no other country was breeding Atelopus specimens in captivity, a team made up of the IVIC and the Fundación La Salle (funded by International Conservation) requested permits from the government for this, but all requests were denied.

Then, because of the national crisis, the organizations that made up the teams to monitor and preserve the research, weakened: International Conservation—their Latin American headquarters were in Caracas—left the country, as well as many foreign NGOs, and Fundación La Salle was forced to minimize their program to the point of almost closing down entirely. But herpetologist Celsa Señaris, who left the Fundación La Salle to join the IVIC, continued on the project alongside Margarita Lampo, member of the Academy of Science and a scientist at the Institute. In order to monitor the populations of Atelopus cruciger, the IVIC managed to get funding from some foreign NGOs, such as the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund.

The economic implosion dragged the IVIC lab with it anyway, the only one in Venezuela that was able to diagnose chytridiomycosis. For the past year and a half, Margarita Lampo hasn’t been able to diagnose and report to the Ministerio del Poder Popular para Ecosocialismo (former Ministry of Environment) because of the lack of reactives.

In Merida, the conservation center Rescate de Especies Venezolanas de Anfibios (REVA), under the direction of herpetologist Enrique La Marca, created a breeding in captivity program for several endemic frogs that are in danger and they had succeeded in the reproduction of the Mucuchíes frog (Aromobates zippeli) and also created biosafety protocols to eliminate BD in specimens brought from the field. The massive blackout in March set them back a few notches: without electricity, scientists were unable to maintain the proper temperature levels for these amphibians, so even after they tried to cool down the walls and terrariums by spraying them with water, the young population of four species perished—the Mucuchíes frog, the La Culata frog (Aromobates duranti), the Cablecar frog (Pristimantis telefericus) and the Cloudy Forest green frog (Hyloscirtus platydactylus). Only adult specimens were left and they haven’t been able to reproduce yet, tossing the success of their reproduction program out the window. REVA is planning on acquiring a generator in view of the constant power outages.

Because of climate change, the dry season gets drier—which is when the striped toads reproduce—resulting in a population increase that would allow a higher BD transmission, creating new epidemics that could be catastrophic for the species.

Even so, herpetologists are still working hard. The Centro de Conservación Andino de Reptiles y Anfibios de Venezuela—also led by La Marca and funded by the international program Amphibian Ark—was successful in the reproduction of the Mérida collared poison frog (Mannophryne collaris) affected by BD. In 2016, they managed to reintroduce it to the Merida Botanical Gardens, an urban and protected area.

Fifteen years after the last official evaluation, Lampo and Señaris are re-evaluating the conservation status of the Venezuelan amphibian species for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an organization that officially classifies species as extinct or endangered. Although it’s been four years since the methodical monitoring project ended, a team from the IVIC established in 2018 that the three Atelopus sanctuaries hadn’t suffered any negative changes among their population.

However it may be, these animals are threatened because of a crisis where resources needed to save them evaporate, a government that only places hurdles and vetoes the breeding in captivity of species that are critically endangered and protected by national law, and the possibility of a new epidemic breakout that could be catastrophic.

In this political and environmental hecatomb, BD stalks from the backyards of our daily lives: in Caracas, the pathogen has been registered by the IVIC in frogs of the Mannophryne genre located in the area between La Trinidad and El Volcán.

When it comes to our coquis (Eleutherodactylus sp.), the frogs whose nightly song caraqueños know so well, the IVIC hasn’t been able to make the necessary diagnosis yet. Unfortunately, biologist Patricia Burrowes has already detected BD in coquis in Puerto Rico, making it possible for the fungus to be present in the Caracas species. So the day may come when we are left without their symphony, the day when frogs stop singing in Venezuela.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate