Pachini: A Trans Man Who Became an Obsession to Venezuelans

It’s believed that trans people are a current phenomenon. However, in 1941 there was a case that both fascinated and scandalized provincial Caracas and proved the opposite.

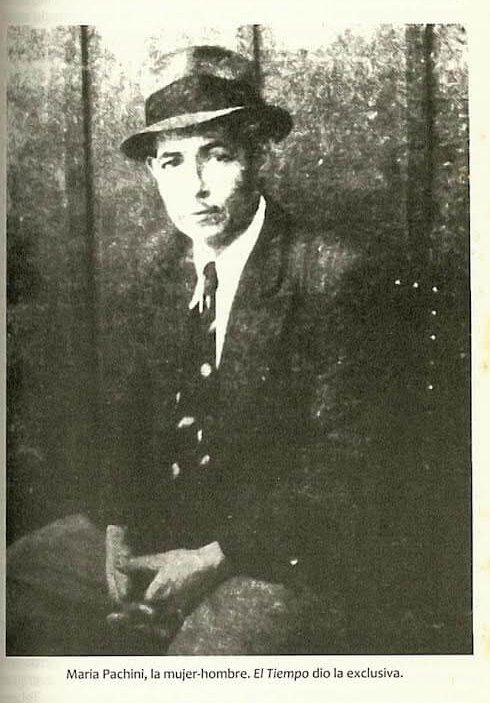

On October 5th , 1941, newspaper La Esfera published a piece about José Manuel Pachini, remembered as “María” Pachini: “An extremely curious, pilgrim, and novel case; perhaps the first known case in the country was discovered yesterday (…) a woman that, impersonating a man, had the audacity to court someone from her own sex and get married with all the benefits of the law.”

The report goes on to tell how Pachini (or Paquini, according to La Esfera) assumed a male role at the age of thirteen and lived as such for almost three decades. He was a bus collector, electrician, barber and nurse, among other occupations. In 1940, while working as a bricklayer, he married seventeen-year-old Bárbara Valenzuela.

The legendary journalist and chronicler Oscar Yanes dedicates a few pages from his book Los años inolvidables to the case of “the wife that isn’t the wife of the man who isn’t a man.” He begins his story when Bárbara Valenzuela reaches the La Vega police precinct to file a complaint: “A week before Bárbara went to the police, the bricklayer came home completely drunk. Pachini couldn’t even stand on his feet so his wife laid him on the bed and began to undress him. When she opened his shirt, she saw several strips of cloth tightly tied to his back. She thought they were bandages, but screamed her head off when she discovered that underneath those strips were women’s breasts”.

Pachini, Yanes claims, would avoid being seen naked by Bárbara under the excuse of modesty and virtue, and when it came to consummating their love, he’d use a dildo. The police picked him up and the scandal, fed by the press of the time, generated fascination and morbid attraction, turning José Manuel Pachini into a Leonard Zelig of sorts.

“On the trolley, on the bus, at the movies, in the parks, and anywhere people would gather, the main topic of conversation was the case of the woman-man.” The few available references you’ll find today will show you the curiosity, derision and rejection of the times.

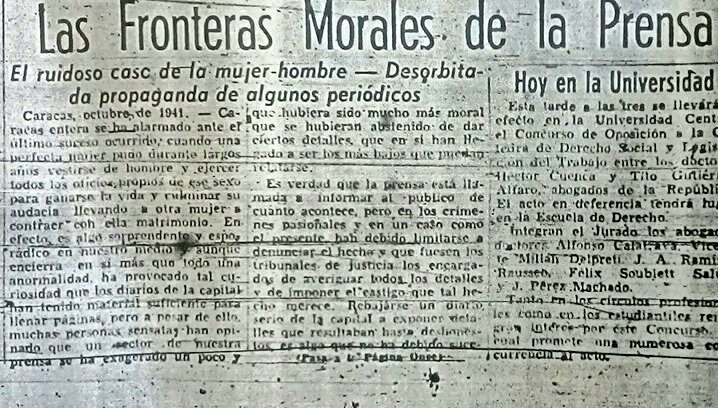

Magazines like SIC made the effort to discuss the role that media plays in cases like this

The most conservative voices didn’t waste time complaining about the attention given to a case, only to “instruct sick and degenerate minds (…) in something that’s so heinous that it should be completely excised, if we want to brag about being a civilized and forward society.” Without directly mentioning the case, an editorial from the SIC magazine, dated November, 1941, calls the press “irresponsible” for the coverage.

Even Andrés Eloy Blanco and Miguel Otero Silva jested about the story in their stage production Venezuela Güele A Oro, where one of the characters buys Pachini’s “dovetailed gold” engagement ring. Andrés Eloy Blanco also wrote for El Morrocoy Azul an imaginary interview to a woman that he describes as a “reverse Pachini.” There’s even a merengue song by Los Antaños del Stadium titled “María Pachini.”

Jurists, Yanes says, ruled that the marriage with Bárbara Valenzuela couldn’t be annulled because it simply was “non-existent.” Pachini’s other relationships with women in other states were uncovered, and he was even involved in séances, which wasn’t reported in the article by La Esfera.

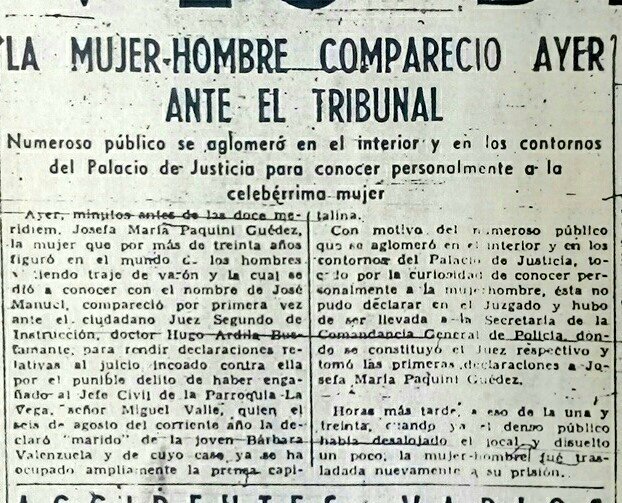

What was indeed reported is the turnout to Bolívar Sq. on the day of the trial: “At 11:00 a.m., Pachini, dressed in a man’s suit, since she refuses categorically to change, was taken to the courthouse and her statement was recorded. A huge crowd gathered at the doors of the old governor’s building and we could all see the sad expression clouding the poor woman’s face. No one dared utter the smallest heckle.”

Headlines of the era depict a nation mobilized to see a sort of freakshow

Society in the capital, facing this subject, attention, controversy and jeers, stayed quiet at least.

The fascination for José Manuel Pachini didn’t last long. The Amateur Baseball World Cup in Havana, where the Heroes del 41 would claim the title, steered the attention and the audience. Nobody really knows what happened with Pachini or Valenzuela. Like Gómez’s doubloons and the Nazi submarines in Paraguana, Paquini or Pachini went on to be an eccentricity from the old days, only remembered by senior caraqueños.

A lot has changed since 1941. The LGBTI community has gained spaces and their rights are recognized in many places, including Latin America. Trans people, as Pachini’s identity would be called today, have also earned recognition and attention, although they continue to be the most vulnerable and stigmatized group in the community.

But in Venezuela it seems that time doesn’t go by if you look at the scarce policies and health services aimed at LGBTI people, the morbidity and the silence of the media when it comes to covering these topics, as well as the conservative groups that invalidate trans people by calling their identity anti-natural, degenerate, or a fad.

“The woman-man.” Since there were no actual terms at the time, the adjectives were straight from sideshows

Truth is that people like José Manuel Pachini have existed in all time periods and places throughout human history, many times on the outskirts of society or spending their entire lives in fear of their secret being exposed. Far from seeing Pachini as a curiosity from yesteryear, maybe we should look at him as a martyr in the name of society’s incomprehension, someone who was truly revolutionary by just being. In short, a brave man ahead of his time.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate