Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Global Relevance

He was way more than a kinetic artist: he delved into the study of the theory and perception of color. Losing him affects not only Venezuelan culture, it’s a global loss.

Photos retrieved

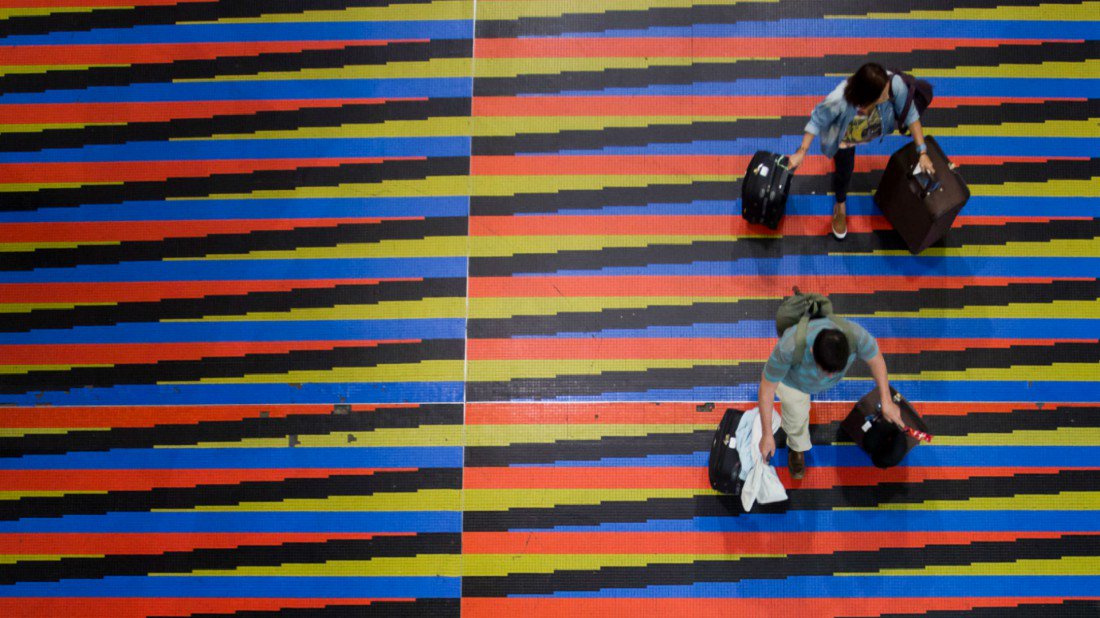

After beloved visual artist Carlos Cruz-Diez passed away in Paris, on Saturday, July 27th, thousands of Venezuelans have uploaded photos on social media of some of his most well-known artworks being walked on by them and their children. Those fortunate enough to know him shared their photos hugging him or talking to the artist.

Actor Edgar Ramírez and Carlos Cruz-Diez.

Cruz-Diez was the utopia of a booming Venezuela, and while he was idolized in Latin America and his native Venezuela, he was less known in the U.S. until about a decade ago.

You could say this was so because Cruz-Diez worked with kineticism, and although this movement was extremely popular in the 1960s and 1970s, it fell out of favor afterwards. Kinetic art was associated with the psychedelic years, a forgotten episode of art history limited to a subcategory in purely local history, in no way affecting the leading artistic movements.

Recently, a few art historians and curators have manifested an interest in this unrequited art, and a couple of exhibitions have sparked interest in the public, making them approach Cruz-Diez and others, like Venezuelan Jesús Soto.

“Cromointerferencia de color aditivo” at Maiquetía airport: a symbol of Venezuelan migrants who say goodbye to their homeland expecting to return. Photo: El Estímulo retrieved.

A pioneer of many resources

Carlos Cruz-Diez (Caracas, 1923) started his career working as an illustrator for several magazines and newspapers, and he later become the creative director of advertising agency McCann-Erickson in Caracas. His first artworks leaned more towards social realism, meant to comment on the sociopolitical conditions surrounding him, but it was his veer towards geometric abstraction what launched his career in Venezuela and abroad.

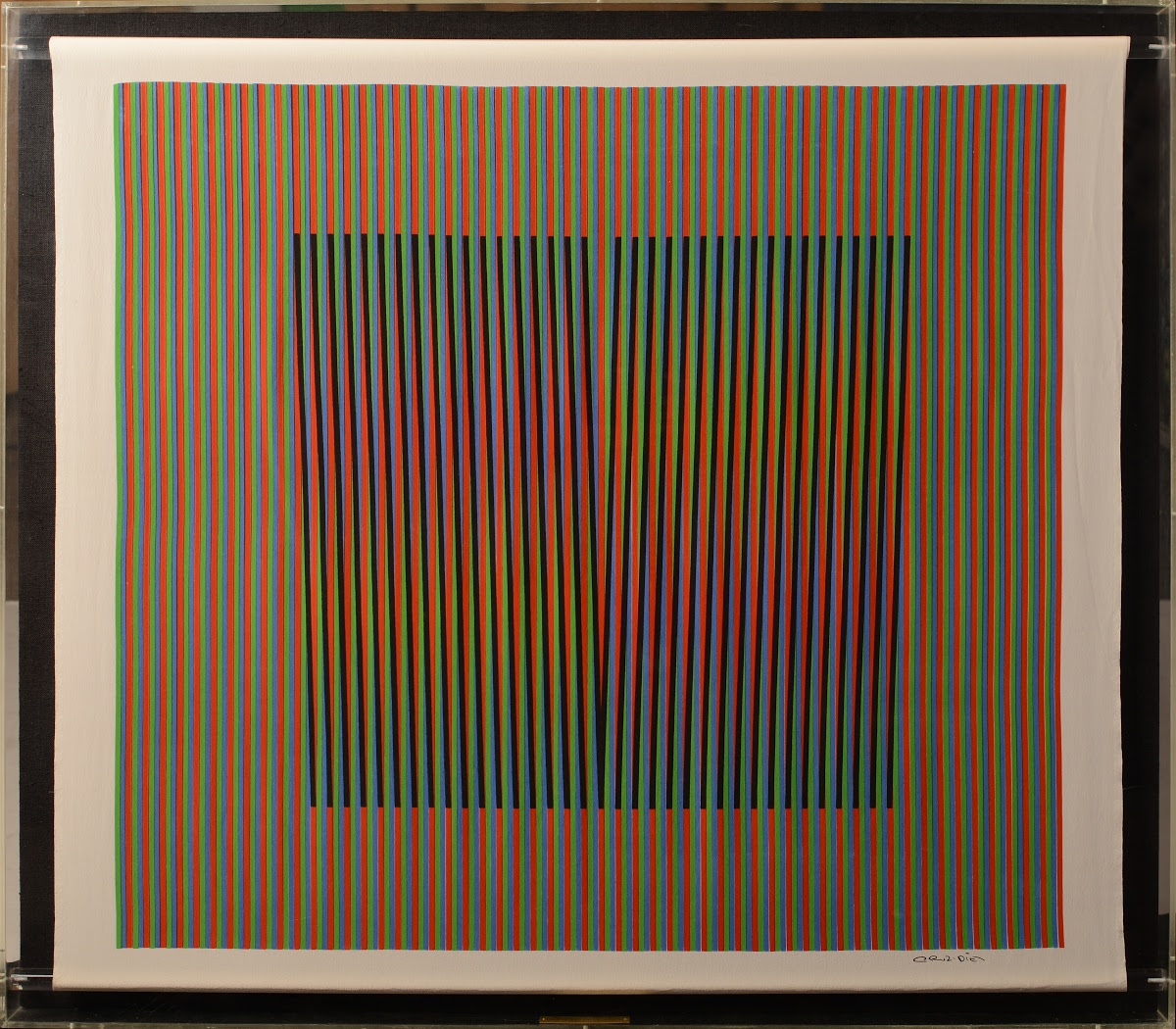

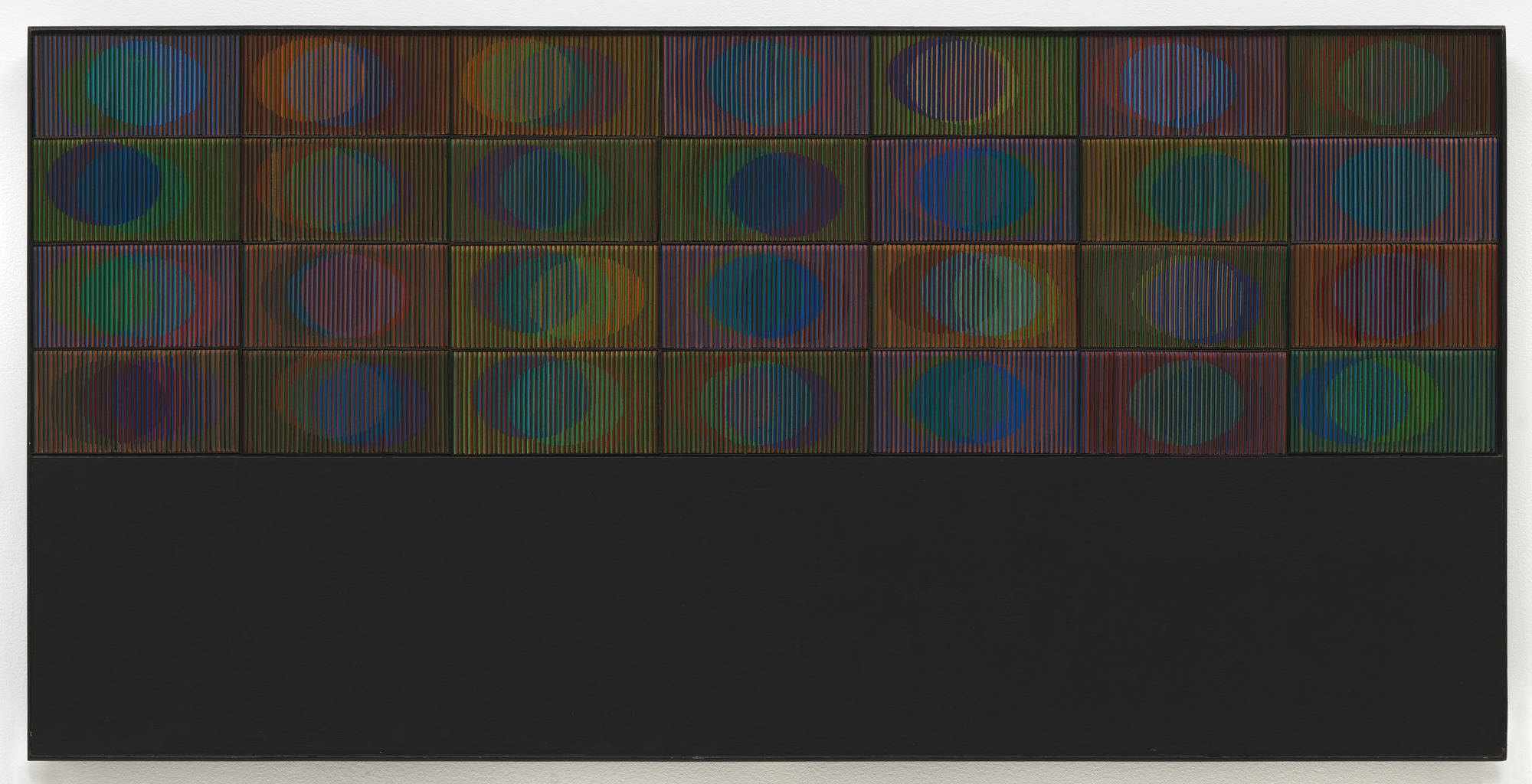

He moved to Europe in the 1960s and took part in the leading exhibitions of Paris, London and New York, featuring kinetic and optical art. The artist’s experiments expanded notions about color, and he created several series of major works exploring optical effects, including Fisicromías, Transcromías, Inducciones Cromáticas and Cromosaturaciones.

Inducción cromática (Chromatic Induction) 1978. The artist’s experiments expanded notions about color, and he created several series of major works exploring optical effects.

Cruz-Diez’s pioneering contribution to the experimental practices in the 1960s and 1970s proposed the dematerialization of the object to create environments that involve the body, the senses and the subjectivity of the spectator. In his research with color and perceptual structures, Cruz-Diez explored the artwork as a field of active participation through the use of light, movement, and space.

The artist’s solo exhibition in the Venice Biennale of 1970 launched him to stardom. In the following decades, he’d work in projects on an architectural scale. Also, during this time, Venezuela was a booming oil-rich country that commissioned impressive public art projects, like the Color Aditivo crosswalks in Sabana Grande Bvd. in Caracas (1975), the Ambientación Cromática in the Guri Power Plant (1977), or the Cromoestructura Radial in Barquisimeto (1982), just to name a few, all from this globally successful artist.

Monumento al sol naciente. Barquisimeto, Lara. In his research with color and perceptual structures, Cruz-Diez explored the artwork as a field of active participation through the use of light, movement, and space.

Cruz-Diez also made public art projects in France, the Dominican Republic, Switzerland, Ecuador, South Korea and other nations.

Carlos Cruz-Diez inaugurates his monumental artwork of architectural integration for the Miami Marlins ballpark. The work, consists of three walkways with a total area of 1672 m2, of a Double-frequency Chromatic Induction which can be appreciated by both spectators and all those who wander through the gardens adjacent to the stadium.

At the Americas Society in New York City (2008), he exhibited a Cromosaturación. MoMA’s collection has a Fisicromía, acquired after “The Responsive Eye” exhibition, in 1965, and several pieces that belong to the Patricia Cisneros Collection will be part of MoMA’s, now. You can see his work at world-class museums like the Centre Pompidou, and in the last couple of years he received several commissions for chromatic intervention on crosswalks, such as the one produced for the Miami Marlins Ballpark Stadium, in 2012.

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Physichromy 114, Paris, March 1964

A living legacy

Cruz-Diez lived long enough to see the collapse of his country, but also the abandonment of many of his works, like the one in Plaza Venezuela, Caracas, or the vandalizing of his Muro de Inducción Cromática por Cambio de Frecuencia, commissioned for La Guaira’s 400th anniversary, the longest kinetic artwork in Latin America (demolished by the chavista regime in 2005).

Chromatic Induction by change of frecuency, at La Guaira port.

In Paris, he’d open his studio to students, art lovers or colleagues who wanted to chat, and during his last decade he spent many years in Panama, where his son Jorge founded Articruz, an atelier for artists dedicated to the production of works of contemporary art. Anyone who met Carlos Cruz-Diez will mention his enthusiasm, generosity, kindness and openness.

As any Venezuelan my age, I grew up knowing him through many of the architectural integrations he created along the country but, writing one of my postgraduate dissertations on his oeuvre, I was fortunate to speak to him on several occasions, even working on his first solo show in America, (In)formed by Color, presented at the Americas Society, in 2008. In his old age, he maintained his curiosity and thirst for knowledge, forcing himself to go to his atelier daily, and was adamant about being up to date with new technologies, using computers to visualize his projects and artworks.

Cruz-Diez sowed the seed of love for art in his children and grandchildren, who will make sure that his works are taken care of, so future generations can continue to appreciate and marvel at them. There’s also the Cruz-Diez Foundation, which aims to preserve, promote and spread the artistic and conceptual legacy of the Maestro, and they’re vigilant and invested, working towards the conservation and repair of his deteriorated works in Venezuela.

We continue to mourn the passing of a visionary who created a universal artistic language through the research on color, a man who made our world a more vibrant one.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate