The Doctor of the Jail

Carmelo Gallardo is one of the 11 doctors who were detained in the protests of April 30th, 2019, in Venezuela. He’s a hematologist and chief the Blood Bank of Maracay’s Central Hospital, in Aragua, accused of resisting authority, obstructing a public road and incitement. This is his wife’s testimony.

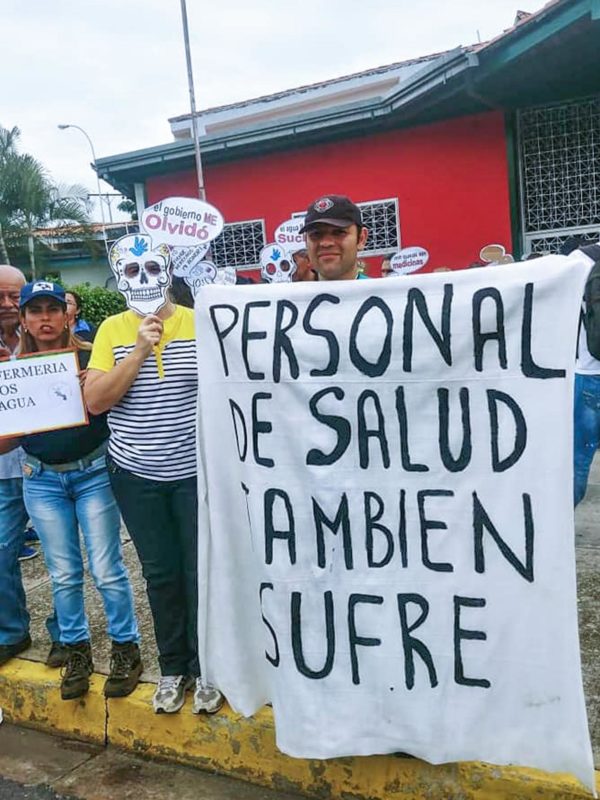

Photo: La Vida de Nos, retrieved.

Angélica cried hard on her birthday. We, her parents, couldn’t be there to celebrate her 12th anniversary, on May 6th. Since her dad was arrested on April 30th, I’ve had no time to look after her, or her younger brother.

And they ask about him every day. My husband, hematologist and internist Carmelo Gallardo, chief of Maracay’s Blood Bank in Aragua, went out to protest on April 30th along with many others, after caretaker President Juan Guaidó called that morning for a national rebellion.

We’ve always been afraid of what they might do to us and I wasn’t totally surprised by the arrest. I’ve been with Carmelo for 12 years and I know he’s a staunch defender of human rights; he’d give press conferences decrying the health crisis in the Central Hospital, he’d go to peaceful protests demanding supplies and medicines for his patients.

That day, he left on his bike from his parents’ place, to demonstrate. During the whole hassle, a lady fainted and he helped her; next thing he knew, a group in civilian clothes, allegedly secret police agents, jumped him, stole his shoes, his phone and detained him.

I knew about those details later, when I got the call confirming his detention, around 9:00 p.m.; the last time I had spoken to him was 14 hours earlier.

Carmelo Jr., my youngest, was sleeping with me. He woke up upset, asking for his dad. I had to tell him he was busy attending sick children. I didn’t know what to do! I had a panic attack and started crying, I dropped to the floor until my mom asked me to calm down. The baby was nearby and he saw me.

Angélica found out on social media. When one of her teachers mentioned the detentions of several doctors and showed pictures of them, she immediately identified Carmelo. She asked me when she got home, “What happened to dad?”

I couldn’t keep the truth from her. She cried. She didn’t understand why Carmelo, who had taken her to paint murals for campaigns for blood donations, was in prison.

On May 1st, we finally knew he was alive. He’d been taken to the Páez Garrison, a military facility right in downtown Maracay. That’s why no human rights activist or Foro Penal lawyer in Aragua could locate him, the Paéz Garrison has never been used to hold people detained in protests.

He was there for three days. On May 2nd, he was transported at night and in handcuffs to the Justice Palace for his preliminary hearing. Judge Yasdeise del Valle Herrera, from the Seventh Control Court, indicted him for resisting authority, obstructing a public road and incitement, sending him to the Alayón Detention Center.

Two days later, I managed to visit him. He cried when he saw me, a calmed cry. He hoped to be out soon, but he’s still in there. Still helping.

“Wherever I am, I’ll practice medicine and I can still do something for my country in here,” he told me. He needed a stethoscope, basket balls, brooms, paint, brushes and books. He had already examined the other inmates and taught them how to wash their hands. He asked them to pull the mattresses out to the sun, to avoid mites.

The paint was for the walls, so that the place didn’t look as dirty. The books were to teach inmates to read and write. Carmelo is on his sixth semester of Education at the National Open University, now he’s a teacher while in prison. Perhaps it’s a vocation he inherited from his parents, Olga and Carmelo, both retired.

Olga has severe hearing problems and we’ve been unable to cover the cost of the prosthetic she needs to hear for the past two years. She’s suffering a lot with the detention of her only son, her support, her everything. Carmelo Sr. is healthy as an oak, but he suffers in silence. They won’t find peace until their son is free again. She wants to see him everyday, but visits are only allowed on Wednesdays and Saturdays. She cries so much that the first time she visited him, the inmates cried with her.

We can only wait until he’s out, without lowering the pressure, going out to protest even though we know what can happen to us. Hopefully, my husband will be released soon and we’ll leave the country, something we had considered years ago for the good of the children. It’s unavoidable now.

When Carmelo worked at the hospital, I was also seeing patients in La Victoria and Cagua, along with my work as a nutritionist in the Central Hospital’s Dialysis Unit. We got robbed once; another day, gangsters chased me down the street to steal my car. When they asked for a “special tax” so we could keep the car, Carmelo decided to move around on his bike. He used to be overweight and biking helped him, he’d do over 20 kilometers a day on a round trip between our home and the hospital, in Maracay.

It’s extremely unfair that a man who has done nothing but save lives is in prison today. Carmelo loves his profession, he gives it his best, and his only crime was opposing chavismo.

This story, originally published on La Vida de Nos, is part of the project La Vida de Nos Itinerante, where people from all over the country take part in workshops to improve their skills to tell real stories. Translation: Javier Liendo; second edition: Caracas Chronicles Team.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate