A Country Interrupted

Photo by Gabriela Mesones Rojo

Hello darkness, my old friend

I’ve come to talk with you again

Paul Simon

20 days ago, Venezuela spent four and a half days without electricity when the electric grid collapsed. In some places, such as Machiques, in the Western edge of the country, the electric service was hardly reinstalled. Since then, Venezuelans have spent a large amount of energy worrying about when it will happen again, how long it will last, and how to prepare for the inevitable darkness that will fill our days. Yesterday, another blackout sunk 17 states into the shadows again.

20 days ago, Venezuela spent four and a half days without electricity when the electric grid collapsed. In some places, such as Machiques, in the Western edge of the country, the electric service was hardly reinstalled. Since then, Venezuelans have spent a large amount of energy worrying about when it will happen again, how long it will last, and how to prepare for the inevitable darkness that will fill our days. Yesterday, another blackout sunk 17 states into the shadows again.

Sunset at Caracas during blackout, March 26. Los Palos Grandes, Santa Eduvigis and Sebucan. Video by Arnado Espinoza.

Caracas seems peaceful and serene. The tension and despair we felt during the last 100 hours of national blackout at the beginning of the month have turned into a shy complaisance. “Everyone is acting like it’s Sunday. We got scared the first time, but it’s going to be less and less scary, less important to report the electric failures as news,” says Otilia, as she arrived at her son’s home. “My son has a gas stove. So we have to cook here if we want to have a hot plate.”

“The first blackout made me cry. I was so worried about everything: food, water, connection. This time, I’m trying to cope. I can’t worry to death,” said Arelis, who quietly sat in Sabana Grande Boulevard while chain smoking. “Now, I know how to handle a situation like this, so I handle it. Slowly, I start to feel comfort amidst the catastrophe. This is how we react. I used to think it was a good way to face life. Now I feel defeat.”

“The first blackout made me cry. I was so worried about everything: food, water, connection. This time, I’m trying to cope. I can’t worry to death,” said Arelis, who quietly sat in Sabana Grande Boulevard while chain smoking. “Now, I know how to handle a situation like this, so I handle it. Slowly, I start to feel comfort amidst the catastrophe. This is how we react. I used to think it was a good way to face life. Now I feel defeat.”

What she and others may call defeat is also a simple act of resistance: opening your store amidst electric collapse, trying to stay sane rather than trying to survive, celebrating the little solutions that come to make life a little more bearable. “We plugged our hot dog cart to a battery and we worked our normal schedule. It’s been a slow day, but our clients pay cash and we don’t complain,” said Pedro as he made a traditional con todo for me. Andrés, a baker on Casanova Avenue, on the other hand, wants to complain out loud: “The store next to us got a few hours of electricity. We have no power and no water. There was a time when we had our fridges packed with food for a month. Now we’ve got nothing. This happens, and we don’t even have anything to lose. What will happen next? Will they take the air we breathe?”

What she and others may call defeat is also a simple act of resistance: opening your store amidst electric collapse, trying to stay sane rather than trying to survive, celebrating the little solutions that come to make life a little more bearable. “We plugged our hot dog cart to a battery and we worked our normal schedule. It’s been a slow day, but our clients pay cash and we don’t complain,” said Pedro as he made a traditional con todo for me. Andrés, a baker on Casanova Avenue, on the other hand, wants to complain out loud: “The store next to us got a few hours of electricity. We have no power and no water. There was a time when we had our fridges packed with food for a month. Now we’ve got nothing. This happens, and we don’t even have anything to lose. What will happen next? Will they take the air we breathe?”

Jesús is a shoe cleaner. He lives in Valencia, but works, or tries to work, in Caracas. “I arrived today. Valencia had no electricity and I had no news from Caracas, so I still came to work. Now I have nowhere to stay. I made no money today. I haven’t eaten. I have no way to go back home,” he said in front of the hotel where the international press has found a new home. “I am an expert making bad decisions. But it seems like any decision we make today is a bad one. We try to move on, and there’s a wall in front of us.”

Jesús is a shoe cleaner. He lives in Valencia, but works, or tries to work, in Caracas. “I arrived today. Valencia had no electricity and I had no news from Caracas, so I still came to work. Now I have nowhere to stay. I made no money today. I haven’t eaten. I have no way to go back home,” he said in front of the hotel where the international press has found a new home. “I am an expert making bad decisions. But it seems like any decision we make today is a bad one. We try to move on, and there’s a wall in front of us.”

From Merida, our David Parra tells us violence hasn’t taken the streets, but neither has hope: “People are playing dominoes and cards in the street, drinking some rum, Havana style. Some stores have opened their doors, although most haven’t. The government’s propaganda has worked since the first national blackout. Out of 11 people I spoke to, eight argued that everything was relatively ok until the opposition started fucking everything up again.”

From Merida, our David Parra tells us violence hasn’t taken the streets, but neither has hope: “People are playing dominoes and cards in the street, drinking some rum, Havana style. Some stores have opened their doors, although most haven’t. The government’s propaganda has worked since the first national blackout. Out of 11 people I spoke to, eight argued that everything was relatively ok until the opposition started fucking everything up again.”

Meanwhile, at the state-controlled National Radio, Ilenia Medina says that the country has seen a big celebration of oral tradition, community gatherings, and human connection. But dealing with the hardship of everyday life amidst a nationwide blackout with some sanity is not the same as dealing with an emergency within darkness. Hospitals still report that power plants aren’t sufficient for patients with ongoing treatments, and abroad, migrant families still have to handle the impotence of not hearing from their loved ones in Venezuela for days. The vulnerable have never been so unprotected and hope has boundaries yet to break.

Meanwhile, at the state-controlled National Radio, Ilenia Medina says that the country has seen a big celebration of oral tradition, community gatherings, and human connection. But dealing with the hardship of everyday life amidst a nationwide blackout with some sanity is not the same as dealing with an emergency within darkness. Hospitals still report that power plants aren’t sufficient for patients with ongoing treatments, and abroad, migrant families still have to handle the impotence of not hearing from their loved ones in Venezuela for days. The vulnerable have never been so unprotected and hope has boundaries yet to break.

“We plugged our hot dog cart to a battery and we worked our normal schedule. It’s been a slow day, but our clients pay cash and we don’t complain,”

“We plugged our hot dog cart to a battery and we worked our normal schedule. It’s been a slow day, but our clients pay cash and we don’t complain,”

Most stores remain closed, including drug stores, restaurants, banks, etc.

Most stores remain closed, including drug stores, restaurants, banks, etc.

An open fruit store works in the dark during march 26.

An open fruit store works in the dark during march 26.

Plaza Brion in Chacaito doesn’t feel like the overcrowded square it usually is.

Plaza Brion in Chacaito doesn’t feel like the overcrowded square it usually is.

Sabana Grande Boulevard.

Sabana Grande Boulevard.

“The store next to us got a few hours of electricity. We have no power and no water. There was a time when we had our fridges packed with food for a month. Now we’ve got nothing. This happens, and we don’t even have anything to lose. What will happen next? Will they take the air we breathe?”

“The store next to us got a few hours of electricity. We have no power and no water. There was a time when we had our fridges packed with food for a month. Now we’ve got nothing. This happens, and we don’t even have anything to lose. What will happen next? Will they take the air we breathe?”

Informal street vendors were present from Chacaito to Plaza Venezuela.

Informal street vendors were present from Chacaito to Plaza Venezuela.

A closed bar at Chacao.

A closed bar at Chacao.

Most stores remain closed, while others opened their doors and took cash, both dollars and bolivars.

Most stores remain closed, while others opened their doors and took cash, both dollars and bolivars.

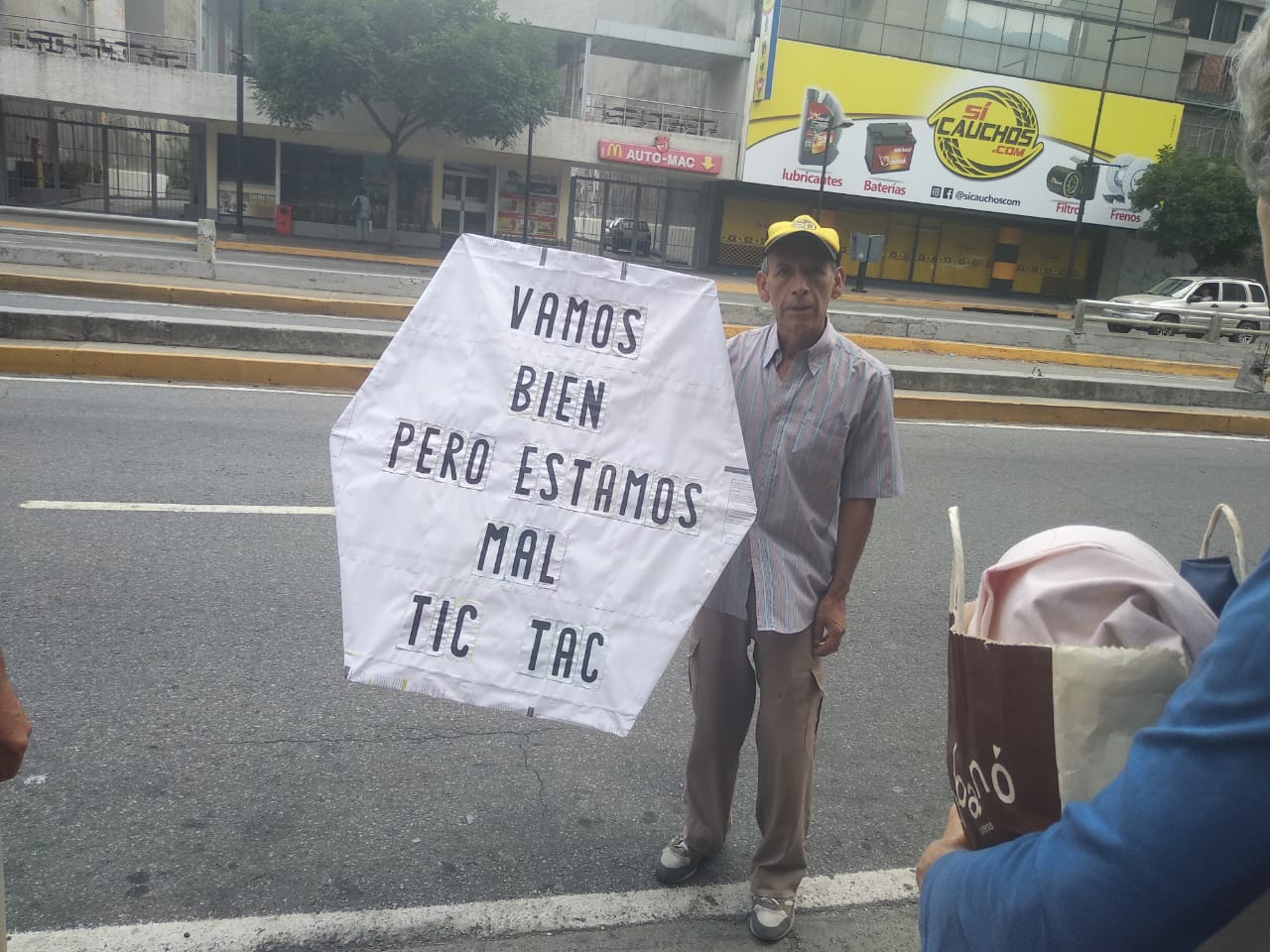

“We’re doing well but things are bad, Tic Tac”, states one of Caracas’ most iconic peaceful protestor of the last decade, Rafael Araujo.

“We’re doing well but things are bad, Tic Tac”, states one of Caracas’ most iconic peaceful protestor of the last decade, Rafael Araujo.

A closed kiosk in Plaza Brion.

A closed kiosk in Plaza Brion.

What she and others may call defeat is also a simple act of resistance.

What she and others may call defeat is also a simple act of resistance.

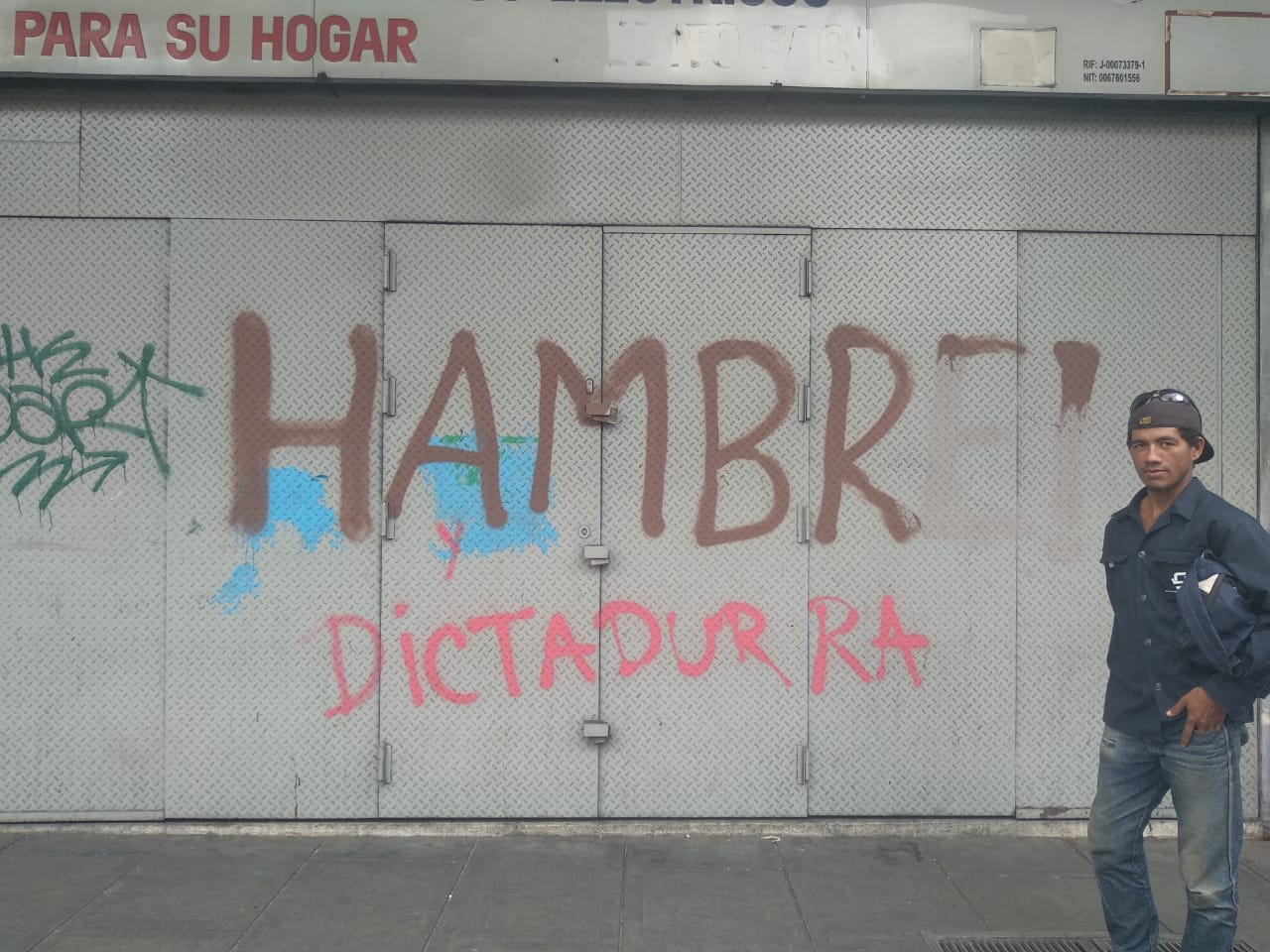

“Hunger and dictatorship”, states a graffity in Francisco de Miranda Avenue.

“Hunger and dictatorship”, states a graffity in Francisco de Miranda Avenue.

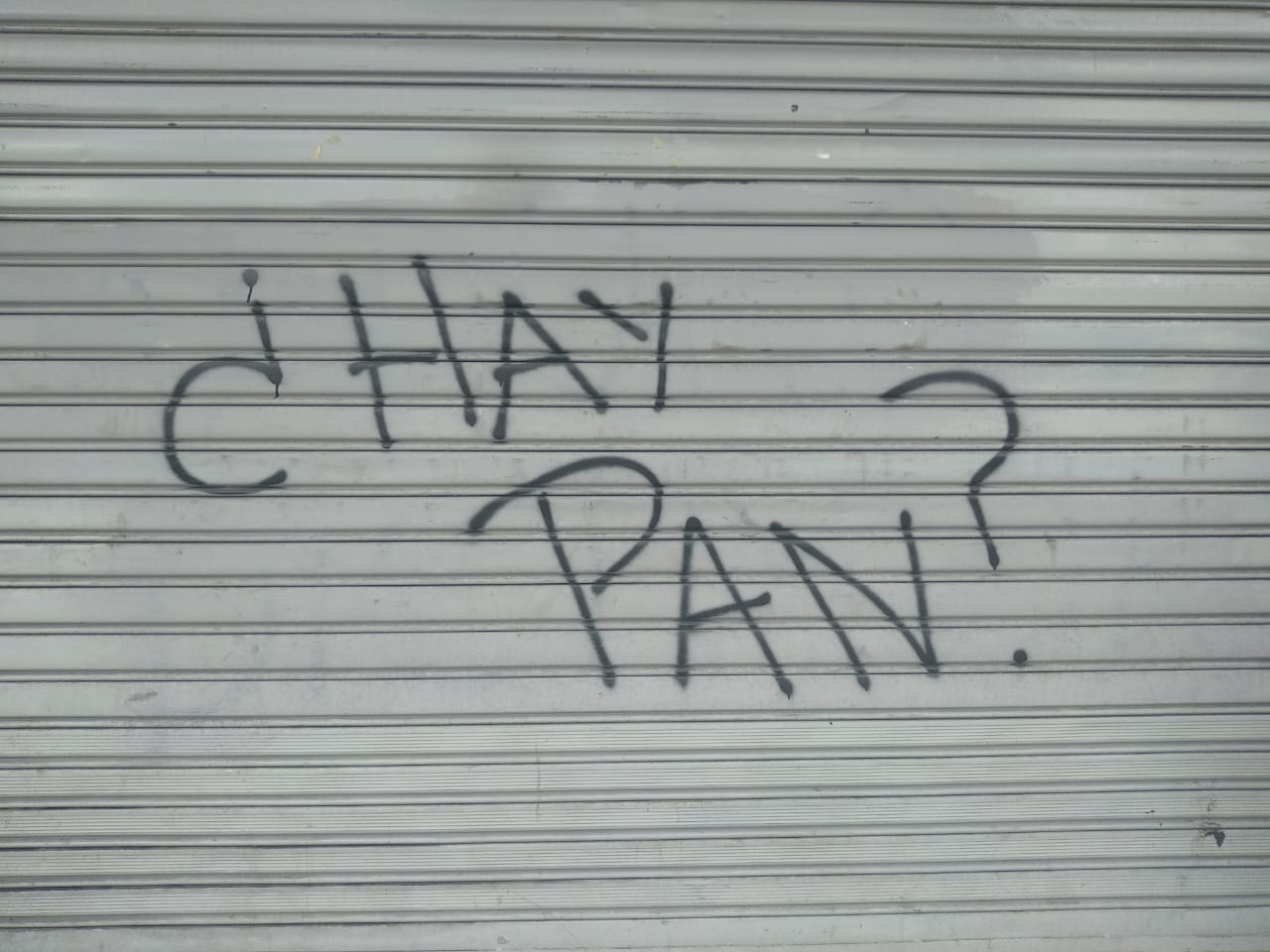

“Is there any bread?” states another question in the same Avenue.

“Is there any bread?” states another question in the same Avenue.

Still, beauty remains. Photo by Javier Liendo.

Still, beauty remains. Photo by Javier Liendo.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate