"They Turned off the Lights and Walked Out"

This is Caracas before Night 4 of the blackout: a ghost town where behavior is increasingly similar to those of apocalyptic novels and movies. Ordinary citizens feel completely abandoned by the State and have no clue of what to expect. The US dollar takes over the survival economy, cash only.

Photos by the author.

I left the office on Thursday afternoon and when I got home the lights were out. I stopped by one of my neighbor’s apartment and we had a few beers while we waited for the power to come back on. Three days later, we still have no water, no electricity, no food, no cash and no explanations (or help whatsoever) from the authorities.

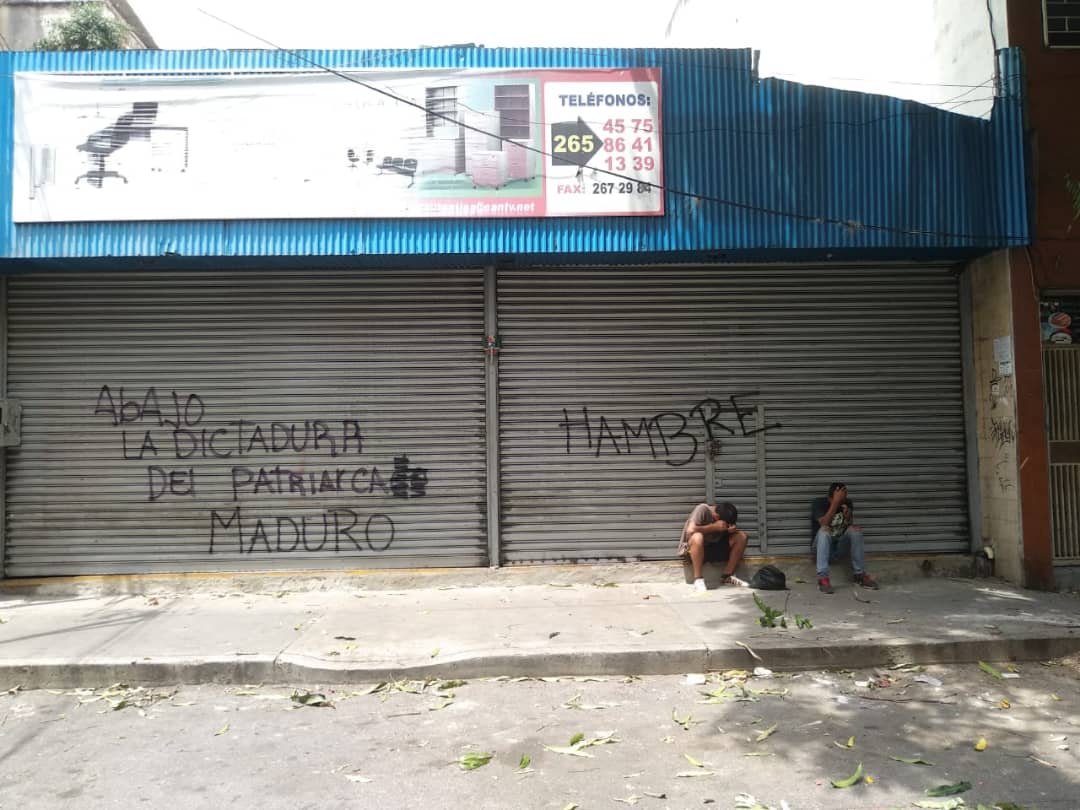

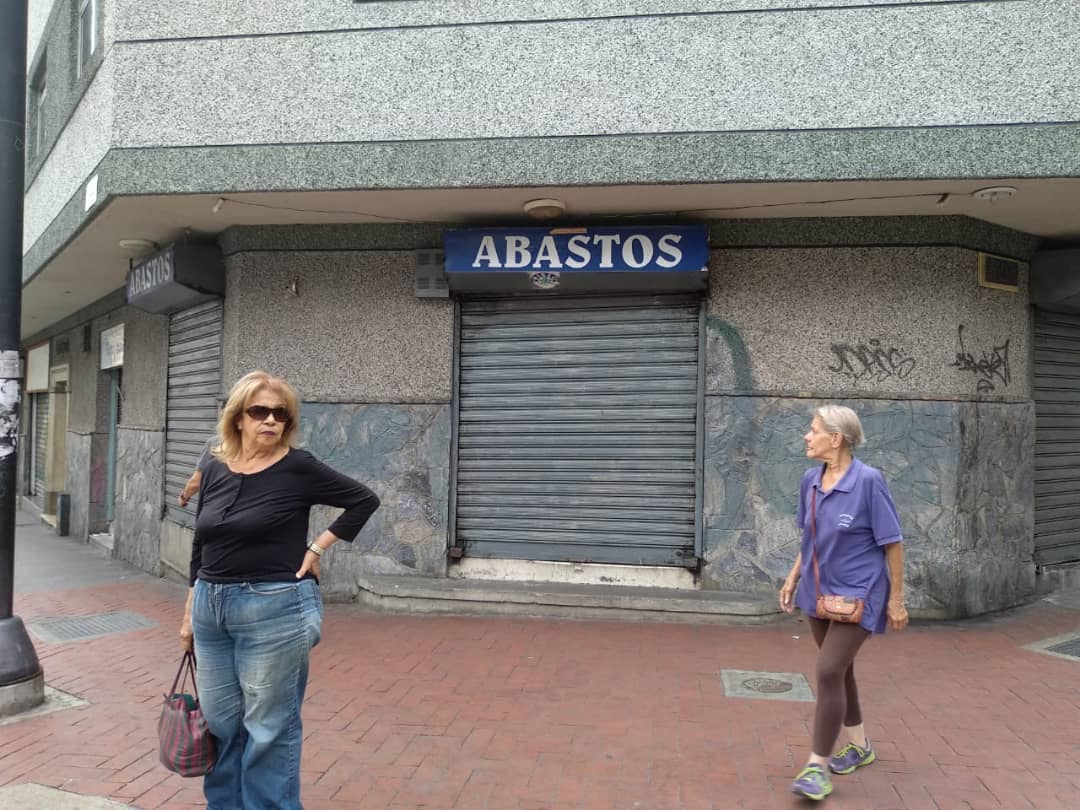

Since then, the country has turned into a ghost town. Survivors roam the empty streets looking for mobile signal, food, water, and a plug. Most stores remain closed; they say hundreds have died in public hospitals or at their homes, unable to contact anyone for help; fear has conquered the streets; looting and small protests have been reported across the nation; fires have gotten out of control. Every hour that goes by without electricity, everything gets harder to find, more expensive, scarier and sadder.

Caracas is a ghost town, Chacao 03/10/18.

Despair is in the air. “We have seen a lot of crazy shit these past 20 years,” says Antonio, a 54-year-old butcher from Falcón. “But we had never experienced anything close to this. They turned off the lights and simply walked out the door. No help is coming. This is what losing a war must feel like. Aren’t they going to help us with water? With food? How much longer until people start dropping dead in the streets?”

Maria walks slowly with a cane, the last rays of sunshine warming her skin. “I am sad it had to happen like this, when we were so close to the end of this damned government. I have a knee problem. I have to walk 17 km to get home. I have a long way to go. When I get there, I won’t have food or water. I don’t even know if my family will be there. If they are, I won’t know how to feed them. And if they aren’t there, I won’t know how to find them.”

“If my family isn’t home when I get there, I won’t know how to find them.”

“We have been talking about an energy crisis for 6 years? 5 years?”, says Pedro, at Plaza Brion. “We know they took that money, stole it. We have seen what they did to places like Maracaibo. They spent 6 days without electricity. Mérida usually has 5 hours of power a day. But this? I never thought they would do this. No shame, no regrets. I think they did this to let us know who’s in charge. Guaidó? Nope, Guaidó won’t fix this, he has no power to do it. They are doing it to remind us who’s in control.” He spots guacamayas flying in the sky. “Look at them, flying high. Life goes on no matter what, right?”

A friend had to stay over for two days because it was impossible for him to get home. Together, we saw rivers of people walking back home amidst the deepest darkness we had ever seen. Then we enjoyed a beautiful starry sky, opened up a bottle of rum, sat in the terrace and talked about all the things the government had taken from us. A neighbor asks if we want burgers (“We are cooking everything we have”) and another yells that he has drinking water in case we don’t. “It’s good to see how you support each other,” says my friend, “I live in Los Valles del Tuy, and my neighbors wouldn’t really share anything with me. You guys are all single, young people. When you have a family to support, in this situation, it’s too hard to help others. We have so little for ourselves.”

A closed “vende/paga” in Chacao 03/10/19.

But there is no way to get through this without help. As days go by, there is less food on the streets, less cash, less water. “I have food, but no way to cook it”, says a 76 year old neighbor from Chacao. “My neighbors have a gas stove, I cook at their place and lend them some food.” Hunger had been a new normal for a while, but now people talk about thirst.

On day two, I walk by the Chinese restaurant in my street and notice its lights are on. They have no power plant but managed to hook up the place’s grid to a car through a converter. They sell 1$ beer, but they know me, so they let me plug my phone without paying. “When we can help you, we will sure help you, Gaby,” says the owner of the restaurant.

Fresh graffiti decorates the closed stores in Chacao, amidst the nationwide blackout on Venezuela (03/10/19).

As I ride through Santa Mónica with a friend, we see people who took out the barbecue to the streets. “This food will spoil. We will rather cook it and give it away than watch it rotting. How many people were prepared for this? None! Who could have seen this coming? No one! How many people have died so far? How many will keep on dying? For the time being, we eat, we share, we try,” says one of the cooks, who displays a magnificent selection of chistorras and morcillas for the neighborhood.

The Caribbean is a cruel, strange, magical place. When I lived in Europe I heard the same remark over and over: you guys are always happy despite your problems. I used to joke, with a friend from the Dominican Republic, that to Europeans we were dancing fools who were never aware of their miserable reality, shaking our hips through cruel dictatorships, poverty, and hardship. But now I know we don’t dance because we don’t know a hurricane is coming: we dance, precisely, because we know the hurricane is already here.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate