Chronicle of a First Time Hallaca-Maker

After 72 hours of cursing brittle banana leaves, contentious almond-roasting, YouTube scouting, Scannone-hating and pork lard handling, I made my first hallaca. It was gruelling. It was worth it.

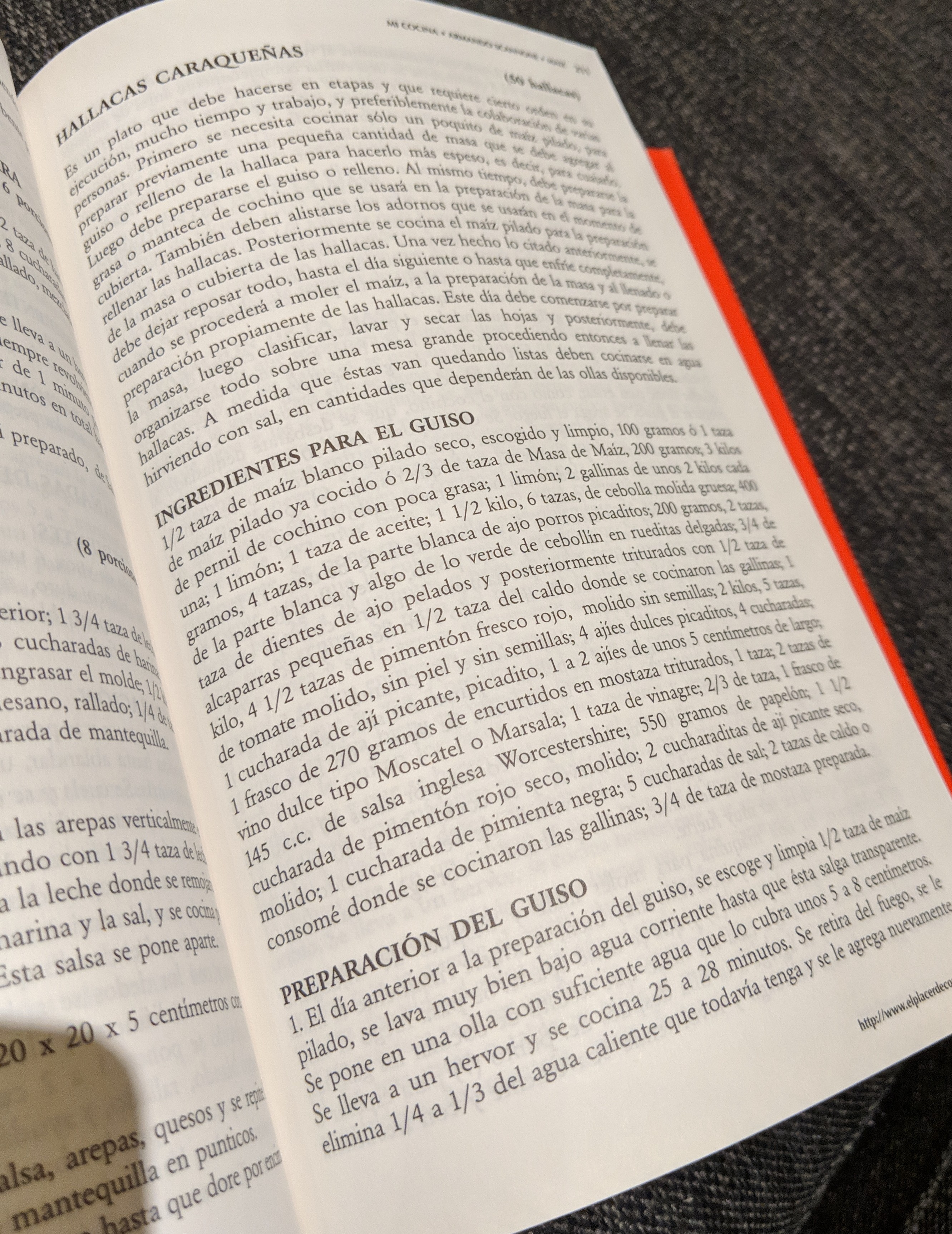

The recipe for “Hallacas Caraqueñas” in Armando Scannone’s celebrated red book runs to seven pages. Not normal pages, either: seven pages of tight-packed, no-paragraph-break, small-font Scannone cannonical wisdom.

You glance at it like a climber at the bottom of the Matterhorn: it’s an insane undertaking, the Venn Diagram overlap between Venezuela’s most famously complicated dish and its most detail-obsessed food writer.

Scannone can over-complicate any dish, and when it comes to Venezuela’s iconic Christmas centerpiece, he just goes hog wild.

Scannone can over-complicate any dish, and when it comes to Venezuela’s iconic Christmas centerpiece, he just goes hog wild.

It’s only when you get to the masa section, halfway through this treatise, that you grasp there’s no hope for mortals here: rather than calling for Harina PAN, like a normal person, Scannone wants us to make our masa from maíz pilado, a shocking 19th-century atavism that’ll add eight hours of work to what was already a two-day undertaking.

It brought to mind the lovely scene in Julie & Julia where the 21st-century Julie guffaws at 1950s Julia’s helpful note that she’s written a cookbook for “servantless American cooks.”

Scannone has no such compunctions — the kind of rococo excess in his Mantuano hallacas takes it for granted that there’s a señora de servicio in the mix. I, like Julie, am servantless, so I do the logical thing: divide all quantities in his ingredient list by four, add “Harina PAN”, and go on a shopping spree at the Sabor Latino on Belanger Street.

I try not to dwell too much on the prices, or how unfair it is I can go to a single store to find all hallaca ingredients in one go, (plus afford them). These things no longer happen in Venezuela, I realize, but there’s no use draining the Christmas cheer from proceedings.

It’s my first year making hallacas, actually. I mean sure, I’ve helped other people make theirs for years and years, but as everyone knows being in charge of the overall operation is different.

Within maybe 20 minutes I’m crossing the last item off my list: four packs of frozen banana leaves —imported from the Philippines, no less.

It’s my first year making hallacas, actually. I mean sure, I’ve helped other people make theirs for years, but being in charge of the overall operation is different.

There are a zillion steps, obviously, but it’s not the number of steps that makes the process so daunting. The guiso —the meaty filling— isn’t actually hard to make, nor is the caldo — the stock you’ll need in like four separate steps. Even the masa, in all its lardy goodness, is relatively straightforward, when you get down to it.

What nobody ever tells you is that the entire reason hallacas are hard is the banana leaves.

It’s funny: as you eat an hallaca, the leaves are the last thing to draw your attention. It’s just the wrapping, right?

If only.

Brittle, enormous, easy to rip and hard to work with, banana leaves turn out to be almost comically ill-suited at the task of containing an hallaca. But you’re stuck with them: everybody understands that the banana-leaf-on-masa action is where hallaca magic happens.

Trying to figure out where to start with them, we turn to Uncle YouTube for advice. In the first video that comes up, a matronly lady from el interior stares into the camera, whips out a huge machete, heads to her backyard, and gamely chops down a banana leaf from her tree.

My wife Kanako and I stare out our at the snowy wastes of our Montreal backyard: nary a banana tree in sight. This isn’t going to work.

YouTube has no antidote to the drudgery of the hojas.

To decide to make hallacas is to accept this nonsense: hours of cursing under your breath, wash-cloth in hand, as leaves rip when you so much as look at them wrong. Hours of messing around with bbq tongues as you dip them in boiling water one by one to try to make them a little more elastic and less brittle. Then again, what did you expect? You’re trying to use a banana leaf as saran wrap, it’s preposterous on its face.

It took two people a whole morning to do this — and remember, we’re only doing a quarter of Scannone’s quantities.

After a lunch of instant ramen —face it, nobody’s gonna be cooking lunch halfway through hallaca-making— we finally get to the fun part: adorno-time. Here, the unexpected strikes as Kanako demands we add an extra step to Scannone’s list.

“The thing I hate about hallacas is the almonds are never crunchy enough,” she proclaims. “That’s why you always pick them out of your hallaca. I’m going to re-roast these before putting them in.”

I’m at a loss for words.

“But baby,” I try to reason with her, “our kitchen already looks like a bomb went off here. Besides nobody adds steps to the Scannone recipe, that’s not how it works. You cut Scannone’s corners, you don’t add new corners. Cutting Scannone’s corners is as much a Venezuelan Christmas tradition as Ponche Crema!”

It’s no use, she’s already heating a skillet to roast her almonds on.

Kanako may not be in any way Venezuelan, but she’s the one with the fine motor skills around the house. As the process goes on, she grasps that I’m just going to destroy all the banana leaves if she lets me do it. Soon she’s deciding how much of which adorno goes in each hallaca — advocating for a shocking, unheard-of three almonds (roasted almonds) per unit.

And folding the damn things? She doesn’t even let me try. Little by little I find myself getting sidelined, a kitchen coup has gone down, and I’m in my own private La Orchila.

A tamal is just an hallaca that’s given up.

At the end of all this, as I’m cleaning up the absolute disaster Scannone’s red book has turned our kitchen into, I reflect on the whole over-complicated ritual.

What you’re left with, when all is said and done, is wonderful — but it’s also, undeniably, a tamal. OK, we don’t call it that, and sure, it’s a far-over-the-top tamal, a churrigueresque tamal with all kinds of weird-ass ingredients that no normal Mexican or Guatemalan would ever put in a tamal (capers, anyone?) And yet, it is recognizable as a tamal to anyone in the region.

Actually, I thought back to the first time I’d had a tamal, here in Canada, at a nice Guatemalan restaurant nearby. I hadn’t known what a tamal was going in. It is, in effect a super-simplified hallaca, and I remember the shock of recognition — a mix of anger that my teachers had lied to me telling me these were uniquely Venezuelan and disgust over the sad, sickly-looking, onoto-less grayish masa and the dearth of adornos.

My early conclusion was that a Central American tamal is just a phoned-in hallaca: a spiritless thing made by someone who doesn’t understand Christmas. Also, a tamal is an hallaca that has given up its hopes and dreams.

Scannone, for all his impossible over-elaboration, gets this dish right. And as I bear down on the crunchiness of a roasted almond in a sea of soft, lardy masa, I’m forced to accept Kanako does too. With hallacas, the basic spirit is that more is more.

So yeah, absolutely do roast those almonds. It makes a difference. And, actually, you know what? Fuck tamales. An hallaca is the same kind of thing as a tamal in the same way Roque Valero is the same kind of thing as Marlon Brando.

…come to think of it, maybe next year we should make them from maíz pilado.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate