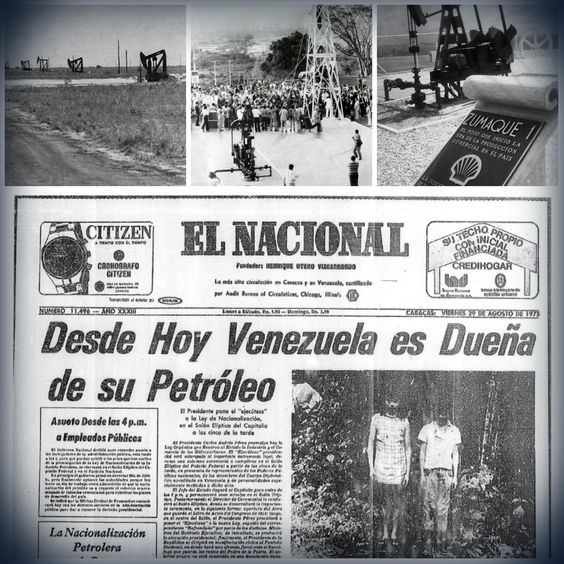

How the Oil Debate Changed Venezuela After August 29, 1975

During Carlos Andrés Pérez’s first presidency, a law was passed so Venezuela could benefit the most from oil revenue. It was well thought out and, most importantly, well executed. It would change our relationship with our natural resources forever.

Photo: Shorthand.Social

The long and chaotic process leading to the statization of the oil industry on January 1, 1976, started with President Carlos Andrés Pérez’s initiative to create a commission through a decree on March 22, 1974, scarcely ten days after taking office. This process changed the dynamics of the entire region, and paved a new path for Venezuelan economy.

Its first article reads: “An ad-honorem commission is created to study and analyze the alternatives to carry out the reversion of concessions and the assets tied to them, so that the State takes control of the exploration, exploitation, manufacturing, refining, transport and marketing of hydrocarbons. The commission must focus its recommendations based on the proposal of a national energy policy that takes into account the entirety of our energy resources and the country’s long-term needs.”

The commission was chaired by the Mining and Hydrocarbons Minister and made up of a long list that included every sector linked to the oil industry. The commission was given six months to produce results. On December 23, the commission delivered its report, a rationale and a Draft Framework Law that gives the State full control over the Hydrocarbons industry and trade. On March 11, 1975, the Mining and Hydrocarbons Minister presented the Draft Law before the National Congress for discussion. Thus started the parliamentary debate, perhaps the last in-depth discussion about the oil industry in Venezuela. Not a small thing, considering its great importance.

Article 5 left a window open for the State to contract oil industry activities with foreign companies.

On April 2, the National Congress created the Special Sub-Committee of Oil Nationalization that convened a period of consultation between April 15 and May 8. All actors gave their opinions during this process. Considering the relevance of the oil matter, the list was very long and the sessions were exhausting. Article 5 was the hardest, followed by articles 1 and 12. The final speaker was lawmaker Celestino Armas, since lawmaker Arturo Hernández Grisanti, head of the Permanent Committee on Mining and Hydrocarbons, chose not to participate in the debate and left Congress. The Chamber of Deputies made changes to article 5 and, when the text for the Law reached the Senate, life senators Rómulo Betancourt and Rafael Caldera took the stand, as well as Gonzalo Barrios, then National Congress Speaker. The three speeches constitute historical documents about the oil debate, since both contextualized the events in national history, reminding us about the long process that led to this decision.

Besides the Draft Law presented by the Committee, other two projects were discussed: that of the MEP and that of COPEI, both coming from the Sub-Committee and later reaching the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Today we know, thanks to a party’s confession, that President Pérez himself penned article 5. He said so in the book Carlos Andrés Pérez: memorias proscritas written by Ramón Hernández and Roberto Giusti. He said: “My mind was so clear at the moment of oil nationalization, that we imposed article 5 of the Oil Law, which Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo called a floppy nationalization, while Caldera said that it wasn’t an oil nationalization but an “oil giveaway”… Article 5 was my idea. It wasn’t easy to include it in the law. I persuaded Rómulo Betancourt about the need for it, but many in the party didn’t agree, especially Arturo Hernández Grisanti, who left Congress. He asked for permission not to vote on the Law of Nationalization due to article 5. That’s history.”

In hindsight, the controversy reached astonishing extremes. Article 5 left a window open for the State to contract oil industry activities with foreign companies. Moreover, these associations always included a larger percentage for the State. It’s amazing that something so elemental made Pérez Alfonzo call the nationalization floppy for that reason. On May 7, 1975, in the Sub-Committee of Oil Nationalization, a radical Pérez Alfonzo said: “The best nationalization is that which excludes joint ventures; but it’s important to take that step as soon as possible, even though this is another floppy nationalization.” The former was a reference to iron statization, which the expert called floppy because it didn’t completely shut the door to the involvement of foreign companies in the iron industry. Obviously, the oil matter (and foreign companies) had become an obsession that surpassed the boundaries of reason.

Reading the Chambers’s Journal of Debates is shocking, since it’s mired with all sorts of exaggerations. The best speeches were those of Betancourt, Caldera and Barrios, who argued for synderesis, while Pérez Alfonzo insisted on its fundamentalist stance against foreign companies and, also, on the need to reduce oil production, given its effect on Venezuelan society: “We need to entirely scrap foreign investment in oil… therefore, I don’t think there’s a need for the State to create joint ventures with foreign investments… the fair and convenient decision would be to reduce production and prevent the depletion of that extraordinary resource with this policy of waste.”

Article 5 was approved on July 9, with 104 votes from Acción Democrática against 94 from the opposition.

Lastly, once all propositions were examined, article 5 was approved on July 9 with 104 votes from Acción Democrática and two from Cruzada Cívica Nacionalista, against 94 from the opposition. We reproduce here the final text of the controversial article 5, not before restating our shock: “Article 5°. The State will exercise the activities established in Article 1° of the present law directly through the National Executive or through entities owned by it, which may enter into any necessary operational agreements to better perform its functions, but in no way will these proceedings affect the very essence of the attributed activities.

In special cases and when deemed convenient for public interest, the National Executive or the aforementioned entities, in the exercise of any of the indicated activities, will be able to enter into association agreements with private entities, with such a participation that it guarantees the control on the part of the State and with a determined duration. Entering into those agreements will require prior authorization of the Chambers in joint session, within the established conditions, once they are duly informed by the National Executive of all pertinent circumstances.”

The best defense for the article was made by then veteran Betancourt, as his last central speech about the oil matter in national public life. Betancourt said: “I’ll say that I fully support that article 5, which doesn’t establish but two possibilities: the possibility of operational contracts with the headquarters that will manage the entire industry; or of association contracts, which the Federal Executive couldn’t make without the support of Congress, with both Chambers gathered in joint session. This possibility of associations, since there’s no mention in article 5 about joint ventures, bears some similarities with those escape valves established in the ‘61 Constitution and in the Hydrocarbons Law of 1967 to avoid tying the State’s hands. We could see a moment in which it might be favorable and necessary for the country’s interest to enter into an association agreement. I don’t see that agreement becoming a new phase for giveaways, because I believe in Venezuela and I believe in Venezuelans; because I know that there won’t be any more dictatorships here and that only dictators are capable, out of venality or for other reasons, of disrespecting national interest.”

The process of creating the law concluded with its promulgation and publication in Official Gazette on August 29, 1975, with the final title of “Framework Law that Reserves the Industry and Trade of Hydrocarbons to the State.” This was the end of a long phase and the start of another in Venezuela.

On December 31, 1975, all concessions expired and the control of national oil activity was assumed by the company created by President Pérez on August 30, 1975: Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). The Board of Directors was established in accordance with Pérez’s idea regarding political meddling in the leadership of the nationalized industry.

The justified belief was that anything that was touched by party politics fell apart.

Let’s keep in mind that there was much prevention in public opinion about this matter back then. The justified belief was that anything that was touched by party politics fell apart, and that wasn’t the intended fate of the nascent company. Pérez was emphatic about this. He appointed as chairman of the company, a citizen with an impeccable and exemplary track record in public management, respected by everyone: general Rafael Alfonzo Ravard, who was also an engineer graduated from MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and had entered public life in Guayana in 1953, heading the Committee of Studies for the Hydroelectric Development of the Caroní River, and was later chairman of EDELCA (Electrificación del Caroní, C.A.), chairman of the Venezuelan Corporation of Development and the Venezuelan Corporation of Guayana, dedicating his entire administrative life to developing the south of the country. Back then, no other Venezuelan had the public management and ethic credentials that general Alfonzo had. Pérez chose well and the country felt it.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate