You Know Where Protesting Will Take You: From Citizen to Terrorist

Isaac López and over a dozen of his neighbors went to jail for protesting in their town square. He still has to show up in court every fifteen days and spend his monthly salary defending himself of a crime he didn’t commit.

Photo provided by the author

He was aware, due to his history studies in the University of Los Andes, of arbitrary detentions, tortures and even disappearances and murders of left-wing leaders in the governments that followed Marcos Pérez Jiménez’ dictatorship. He never thought he’d have the same fate under the current government, and would walk out alive to tell the tale.

Isaac López was born in Pueblo Nuevo, old capital of the Paraguaná peninsula, in the very heart of this quiet territory, full of stories of the independence, but beaten by national neglect. The oil boom created the Paraguaná refining complex, which brought about the State’s complete and definite disregard, giving way to prostitution, smuggling, decline in public services and the abandonment of sowing fields, to work in the oil industry.

Isaac, founder of “Tiquiba,” a cultural collective created to take theatre plays evidencing society’s reality all over Falcón, graduated from history and became a teacher, starting a campaign to rescue Pueblo Nuevo’s historical archive, raising awareness for the preservation of Paraguaná’s architectural heritage.

Cultural Collective “Tiquiba”. Photo provided by the author.

Cultural Collective “Tiquiba”. Photo provided by the author.

As the “revolution” began to settle in, the smiles he managed to inspire left the locals faces, replaced by political proselytism. Isaac became increasingly tenacious and critical, which earned him the spite of regional authorities.

First, he was forbidden to continue caring for Pueblo Nuevo’s historical archive, located in the Josefa Camejo Cultural Complex, where he organized singing and poetry recitals, concerts, theatre plays and discussions. The local government banned him from everywhere, until he was isolated from any financing to promote culture.

This tanned, short man, raised in a highly moral Sephardi Jewish family, was arrested in his town, on October 10, 2017.

López got ready to mediate, but the cops went in full-gorillas, starting a savage arrest ritual.

He was getting home after visiting several towns in the Falcón mountain range (a six-hour round trip every day) to find a common scene: several days without drinking water, the banking system out of order, blackouts and people protesting with whistles and cooking pots. He joined them.

The protest took him to the town’s Bolívar Square. Seeing how the moods were heating up, Isaac stepped to a corner of the square, banging his pot. Then they heard the officer giving the order to disperse the protest, pointing at him.

López got ready to mediate, but the cops went in full-gorillas, starting a savage arrest ritual. Neighbors tried to help him in vain; he was beaten and arrested without explanation.

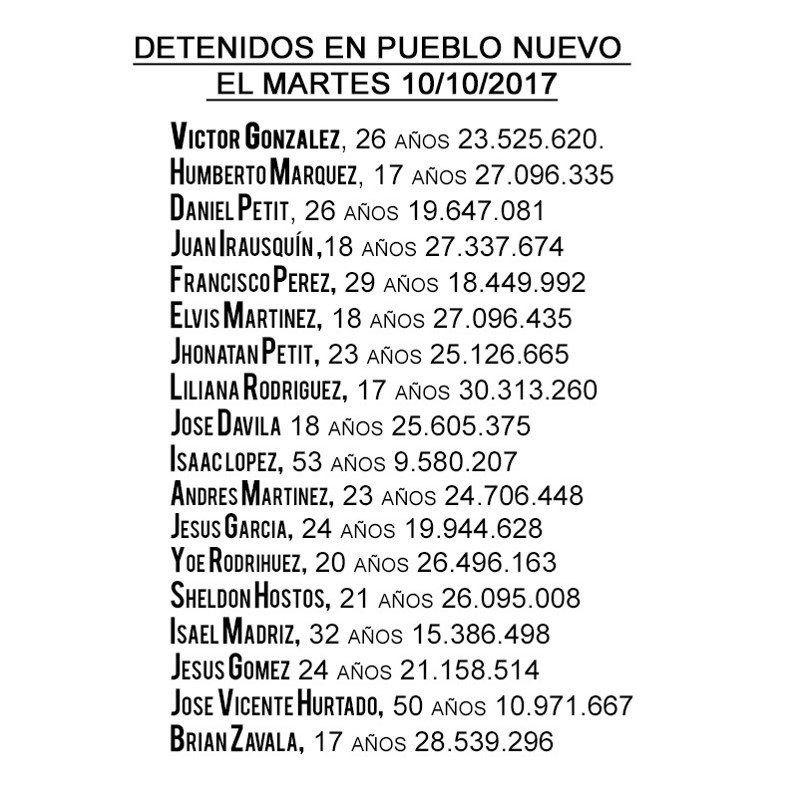

It was 7:00 p.m. when the teacher and historian arrived to Pueblo Nuevo’s 7th Police Precinct. The beatings got worse. Between insults and threats, Isaac was beaten with a piece of wood until he couldn’t get up from the floor. Another 17 people were arrested that night. The town rallied in front of the precinct, screaming for an end to the abuse, for the detainees to be released. Among those arrested, there were four minors, including a 17-year-old girl who was slapped by the officers.

This list was provided by Isaac’s lawyer. Some of the minors were released 48 hours after their arrest.

If you speak Spanish, you can read the story in Isaac’s own words: the officers used pepper spray on them, kept them in the yard under the rain and insulted them until a cop said: “You’ll end up in Ramo Verde for burning the Mayor’s Office, coños de madre.”

They were transferred at 4:00 a.m. on October 11. Isaac pictured the road taking them to some beach where his execution awaited. Piled up, they were put in perreras and that’s how they got Punto Fijo’s 2nd Police Precinct, where they were held in the dining room.

No State authority appeared to explain them why they were arrested. At 2:30 p.m., the CICPC arrived to identify and transfer them, once again, in another perrera. Upon arrival, a relative who managed to see him in bad shape (he had tachycardia) approached him with blood-pressure pills. An officer took them and tossed them on the ground. “Die of a heart attack already.”

On the third day, a prosecutor from Caracas came to see them. More than informing them about the accusation, he came with a sentence ready and approached Isaac, telling him to cooperate and talk with the younger detainees. “You’ll be accused of terrorism for burning the Mayor’s Office. Confess and the punishment will be lighter.”

Isaac and the 17 Pueblo Nuevo residents are still accused of “terrorism”, but there’s no information about the investigation and they keep reporting to court in the dark.

Isaac’s legs failed, but he gathered strength to talk to the rest. That Thursday, October 12, the round trips between courts began, while they remained in dungeons full of feces, poor lighting and ventilation. His health was a rollercoaster.

On Monday, October 16, the verdict came. After hearing his defense lawyer make a detailed presentation of the events (framed, so as to accuse them for burning the Mayor’s Office), the judge released half the group, among them Isaac, but with a presentation regime every 15 days. The rest remained in custody for almost 40 more days.

It’s been nearly 10 months of these events, the case was left without a judge and, in view of the money he had to spend every 15 days to travel to Punto Fijo from Mérida to comply with his sentence (spending his entire salary), Isaac decided to take the risk of not showing up anymore: “I either work to live, or I work to starve while reporting to a court without judges.”

Isaac and the 17 Pueblo Nuevo residents are still accused of “terrorism”, but there’s no information about the investigation and they keep reporting to court in the dark. Paraguaná, now drowned in fear of the repression that ensued that day, has a population intimidated by the absolutism of the “humanist revolution.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate