Venezuela’s Collective Action Problem

The perennial conflict between individual incentives and the common good is the most pressing issue studied by contemporary social sciences. It’s also key to understanding how our country became a mess.

Photo: El Nacional

Venezuela is a basket case and there’s little doubt about it. How is it that the majority of the electorate routinely empowers a group of rent-seekers that have destroyed the national economy, suppressed most individual freedoms and have led to the biggest exodus in the country’s history? Why have they been unable to get organized, challenge Maduro as a collective and take back the political power that’s rightfully theirs? Because that, right there, is the most difficult problem ever faced by mankind, both in theory and practice.

The study of collective action problems is one of the most challenging problems in contemporary social sciences. It’s all about trying to understand what motivates groups of people with separate, sometimes conflicting interests, different views and preferences, to form a consensus and cooperate in a mutually-accepted goal. It focuses on the incentives behind individual choice, and the institutions that channel the aggregation of individual preferences into group-wide decision-making.

Somewhat discouragingly, the last six decades have taught us that getting groups of people to act in their best interest is a pain in the ass, if not downright impossible. Nobel Prize economist Kenneth Arrow minted the Impossibility Theorem, a rigorous mathematical proof of why democracy as a collective action mechanism for politics is inherently flawed. The practical interpretation of the theorem is still up for debate, but it ranges between “the only voting method that isn’t flawed is a dictatorship” and “elections could result in an alternative nobody really wanted in the first place, yet everybody voted for.” Sounds familiar?

The study of collective action problems focuses on the incentives behind individual choice.

Due to its group nature, collective action problems are generally studied through the lens of game theory. Well-known examples include: the “free-rider” problem (individuals are incentivized to “piggyback” on other’s efforts; when everybody tries do so at the same time, nothing gets done); the “Tragedy of the Commons” (self-interested individuals systematically over-consume public goods and deplete them, to society’s detriment); and “Moral Hazard” (each individual will act more recklessly when insured; as a collective, they have to bear an increased cost of protecting against negative outcomes, but individual incentives to take measures against it are undermined).

The case of Venezuela in general, and late chavismo in particular, offers an interesting insight into the difficulties of implementing the will of the majority into action. The dynamics among (and between) the two main groups defining the political map (that is, chavismo and opposition) are very interesting, and terribly contrasting.

MUD: a failed institution for collective decision-making

Most critics of the Democratic Unity Roundtable, also known as MUD, are quick to point out that the main weakness behind the coalition representing the “opposition” since Jan 23rd, 2008 (replacing the infamous Coordinadora Democrática), is that it was conceived merely as a common platform for electoral purposes. To represent the will of the vast majority of Venezuelans that want a break from the current government is a noble endeavor, but by lacking the most essential “rules of the game”, MUD effectively lacked direction since day one.

First of all, MUD exhibits a weak incentive structure for cooperation, as each individual party is interested in appealing to their narrow electorate’s interests (securing state and local governorships, both for vocational and economic reasons), sending the greater good deep down in the list of the party leaders’ priorities.

The MUD remains a leaderless structure in which no single actor serves as final judge.

Furthermore, the coalition has a notoriously dysfunctional voting mechanism: each of two competing factions (Primero Justicia + Voluntad Popular vs. Acción Democrática + Un Nuevo Tiempo) has been historically unable to impose a view over the other in almost every key issue, especially regarding the coalition’s response to the systematic destruction of democratic rights by the Maduro administration. To this day, there’s still a rift between “radicals” and “moderates”, which has led to paralysis and sub-optimal, “common denominator” actions.

The MUD remains a leaderless structure in which no single actor serves as final judge to streamline the decision-making process; even more so after the position of Secretary General was replaced with a high council of leaders from both factions.

PSUV: an institution that solved the collective action problem “a los realazos”

PSUV’s dominant stance in Venezuelan politics is about the oil money flowing through the organization to its constituents. Forget about socialist ideals of nature and mankind; state-sponsored giveaways are the ideological lifeblood of chavismo. Untangle the system of prebendas and it’s evident that the party has a rigid chain of command in which the leader’s orders are strictly followed by all party members with no questioning.

Within the Socialist Party (and pretty much any other chavista movement, including the colectivos), individual incentives are aligned towards “cooperation”, understanding it as some sort of complicity in the party’s distribution of social benefits. That’s because the costs of defection are prohibitive (like the SEBIN manhunt on Eulogio Del Pino) and the benefits of cooperation (i.e. access to the flow of populist cash) are countless.

The way Maduro & Co. have positioned the military on key roles throughout the entire economic apparatus has resulted in a systematic alignment of military interests with the maintenance of status quo.The dynamics of a patronage system with Maduro overseeing an imploding oil economy in default, however, are breeding more and more dysfunction; keeping rent opportunities open for cronies as a way of getting the military in their pockets works, but at the expense of destroying the domestic economy.

Henri Falcón + Kid: an individual defector taking advantage of the opposition vacuum

Former Lara governor, Henri Falcón, decided in late February to bypass the MUD entirely and submit his presidential bid under support of a smaller coalition of nominally opposition parties (Avanzada Progresista, COPEI and MAS), with a political platform deeply grounded in the concept of coexistence with chavismo to ensure policy viability. By design, Falcón’s candidacy is avoiding most collective action problems: there are zero primaries, the campaign platform is “independent” (whatever that means for a politician still dependant on financial support from unspecified third parties) and, most importantly, it signals cooperation with chavismo in terms of a soft landing for their departure, which translates in a strong incentive for chavistas to cooperate.

So clearly two-faced that neither chavista nor opposition-leaning voters feel trustful enough to vote for him.

Falcón’s opportunistic grab of the spotlight is redefining the politics of late chavismo, and it’s perfectly consistent in collective-action terms. He represents the “official” opposition, the one willing to go through all the hoops that chavismo is imposing to partake in elections. Henri is legitimizing the autocracy and, in return, aims for a result that appears to be the best possible outcome for interest groups close to the current government: a transition managed from within chavismo. It represents something seldom seen these 20 years, a critical mass of selfless rent-seekers agreeing to collaborate for the common good. Welcome to the upside down!

However, it’s important to remember that Falcón is pretty much dead to the eyes of the Venezuelan electorate. After his stunning defeat in the bid for reelection in Lara State late last year, pollsters have dissected Falcon’s biggest weakness as a candidate: he’s so clearly two-faced that neither chavista nor opposition-leaning voters feel trustful enough to vote for him. Furthermore, the AP+COPEI+MAS coalition is still far from representing a relevant political force by itself. Consider the mayorship elections of December 2017, in which MUD didn’t participate to boycott the unfair rules: the group took less than 15% of votes, against 65% for the PSUV and 20% for a plethora of independent regional movements who haven’t pledged allegiance to Falcón. That means Henri’s presidential bid critically depends on getting explicit support from MUD. Guess what: there’s currently little incentive in either group to do so. Collective action problems bite again.

Frente Amplio Venezuela Libre (FAVL): MUD 2.0, no bugs fixed

Lastly, we present Frente Amplio Venezuela Libre (FAVL), a group of political and civil-society organizations joining forces to reinvent the “true” opposition. This attempt at fixing the collective action problem by providing direct access to a broad group that wasn’t directly represented in the MUD, including the Catholic and Evangelical churches, the business sector, student/academic movements and even dissident chavistas.

Frente Amplio’s discourse is appealing and the image of all segments of society united against a government that no longer serves them is powerful. Sadly, the first actions of the organization suggest that many of the issues plaguing MUD’s decision-making are still lingering, including the lack of a formal governance structure or any rules to channel the views and incentives of each constituent. We’d love to see more efforts put into the institution itself, for it to reach its full potential.

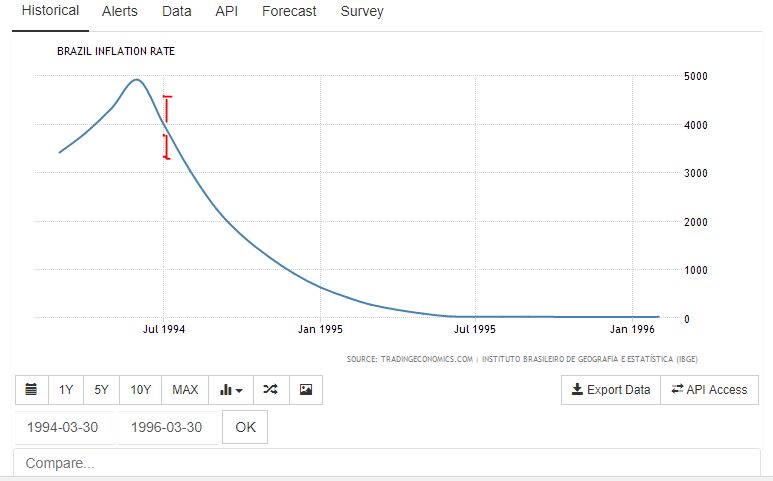

Epilogue: Brazil and the Plano Real

A very interesting parallel to the Frente Amplio in Latin American history comes from Brazil in the 1990s, and Henrique Cardoso’s Plano Real, an ambitious stabilization plan that succeeded mainly because it represented a broad coalition of interest groups among society. The plan was drafted to boost incentives for cooperation (key for success in collective-action problems); the Brazilian economy was suffering from high external debt, four-digit hyperinflation, a wave of corruption scandals and a generally precarious state of economic affairs for a full decade before Cardoso came to power (first as Minister of Finance and only after the plan was successful, as President), sowing the seeds of the turnaround.

The Plano Real, aside from macroeconomic technicalities, mainly consisted on guiding the price-setting expectations of all society around a new unit of account (not an actual currency that you could use to buy or sell goods, yet) determined directly by the free dollar-real exchange rate, with no intervention from the government. The slowdown in inflation was dramatic: less than 18 months after the unit of account was put in place and time was due to roll in the new currency (the Real), inflation came down from over 4000% to less than 100%, and it has never looked back. All agents in the Brazilian economy agreed to revise their expectations by the same measure and timing, and incentives for ever-greater wage and price indexation were instantly gone. Collective action can work!

Source: tradingeconomics.com

The key of success in politics (and all collective-action problems) is about aligning individual interests towards your cause. The two parties that will pit against each other in the elections have, for better or for worse, aligned interests behind their cause; the MUD, on the other hand, screwed up big time and falls more into irrelevance by the day. The biggest losers are the Venezuelan citizens, suffering their collective action problems and enjoying none of the perks monopolized by the rent-seeking elite.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate