ENCOVI 2017: A Staggering Hunger Crisis, in Cold, Hard Numbers

Two out of three Venezuelans are still losing weight. Almost nobody can afford enough food to eat. Virtually everyone depends on subsidized food distribution. ENCOVI 2017 brings harrowing precision to the scale of Venezuela's crisis.

In 2014, a consortium of Venezuelan universities launched a yearly research project to rigorously document social conditions in the country. They called it Encovi —the Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida, or Living Conditions Survey. Last year, it surveyed 6,168 people nationwide, in detail, on a wide range of social matters: income, nutrition, education, personal safety, the state of their homes, etc.

It’s the kind of data that used to be public. As a matter of fact, the government still conducts a detailed yearly Household Survey — it’s just that it refuses to publish the results.

Faced with official opacity, the universities had to pick up the slack.

Encovi is our best data-driven look at social conditions in Venezuela today, a critical institution amid a drought of official data. Because while it’s easy enough to see it’s bad out there, “bad” ain’t good enough for Social Science: if you want to know how bad, you need data.

Poverty

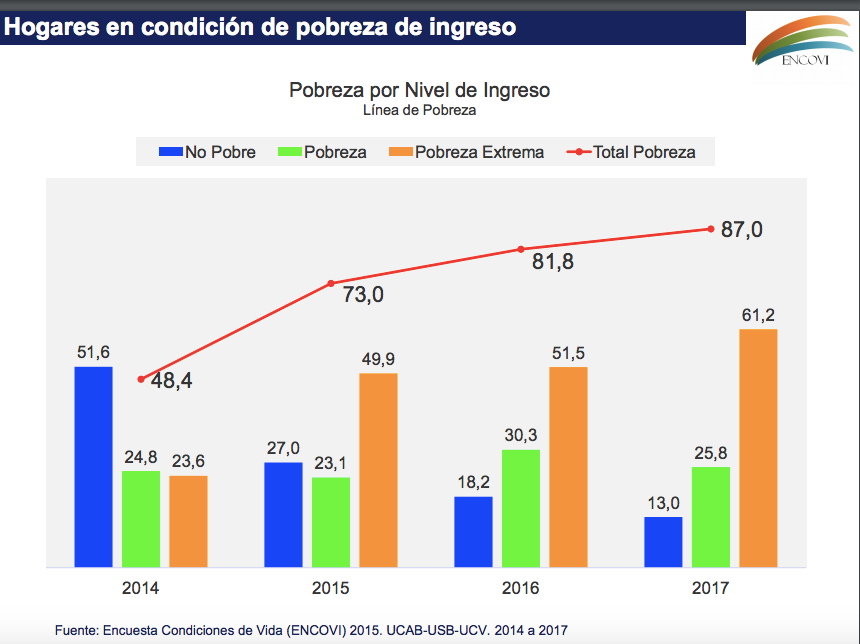

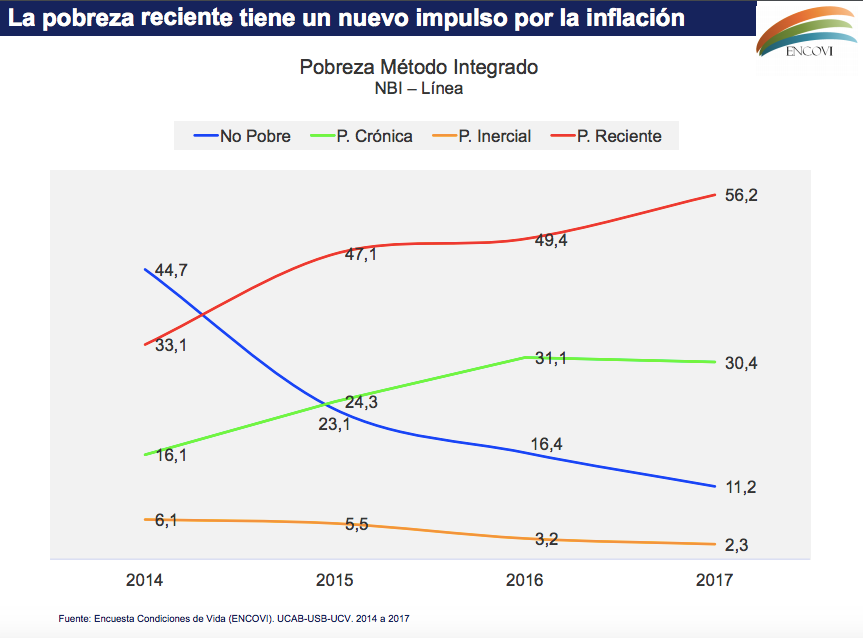

The headline figure is that, by income, 87% of Venezuelans were poor in 2017.

And a shocking 61.2% were living in Extreme Poverty.

The poverty figure always gets tons of press attention, but it’s also one of the trickiest to produce and to interpret.

The poverty figure always gets tons of press attention, but it’s also one of the trickiest to produce and to interpret.

In a high inflation economy, income poverty is almost impossible to get right: with prices doubling every month or two, it’s easy to see that many people’s incomes will be just above the poverty line right after a wage hike only to fall back below it in very little time.

In a high inflation economy, income poverty is almost impossible to get right.

Amid this much economic instability, the indicator becomes finicky: your number can vary a lot depending on whether you do the survey a few days earlier or later. And if you set up your poverty line just a little bit differently, you can get a very different figure.

But in a way none of the caveats matter, because whether it’s 87% or 91% or 93%, all of those translate to “basically everybody.” With inflation turning hyper in the last two months of last year, that “basically” soon becomes redundant: chavismo’s made everybody poor.

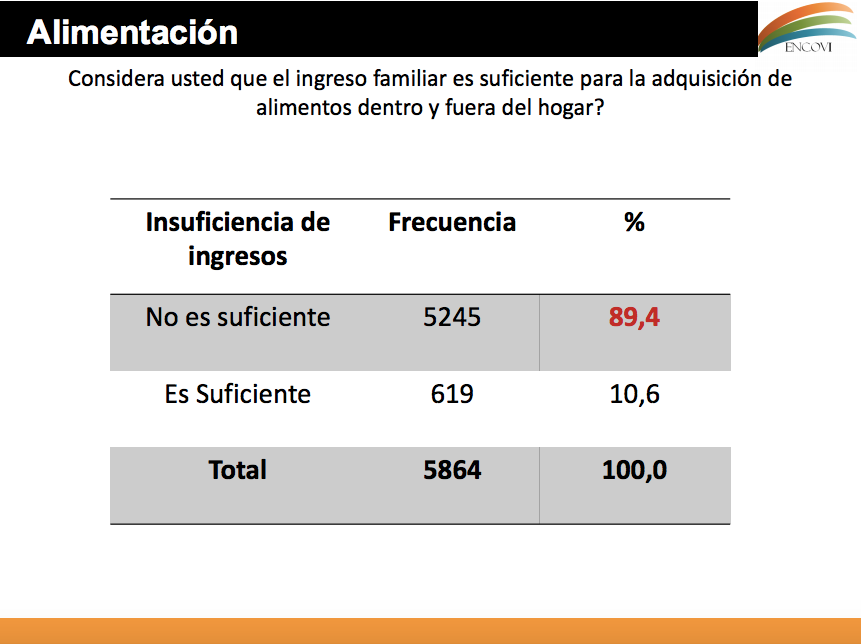

This becomes painfully clear when you ask a stark question: “do you consider your family’s income enough to buy food to consume inside and outside the home?”

89.4% say “No.”

People just don’t have enough money.

A lot of the people who turn out to be poor aren’t the kinds of people you’d classically think of as poor.

A lot of the people who turn out to be poor aren’t the kinds of people you’d classically think of as poor.

Alongside “income poverty” (do you make enough money?), Encovi also looks at “structural” poverty. This approach looks at “unsatisfied basic needs” to construct a poverty measure that’s less exposed to month-to-month volatility. Structural poverty measures things like education, whether your home has dirt floors, whether you have a fridge or a washing machine, whether you have access to sewers and electric service, etc.

To be sure, many fewer people are “structurally poor” than “income poor.” Or, to put it differently, almost two out of every three poor Venezuelans are recently impoverished.

A lot of this is the classic “ex-middle class” story: people who went to school, live in middle-class looking buildings, have middle-class sounding jobs, but don’t make enough money to feed themselves and their families.

Nutrition

Nutrition

The crisis has made hunger almost universal.

61% of surveyed people went to sleep hungry because they didn’t have enough money to purchase food. Encovi considers 80% of homes to be food insecure.

As for what people is eating, the news are bad: The survey shows people’s weekly purchases of food focus mainly on carbs, such as tubers, pasta and rice. The dramatic decrease of protein buying -and consumption- to favor cheaper but less nutritious food that started in 2016 continued last year.

The result is a less varied diet that could put people’s health at risk.

The result is a less varied diet that could put people’s health at risk.

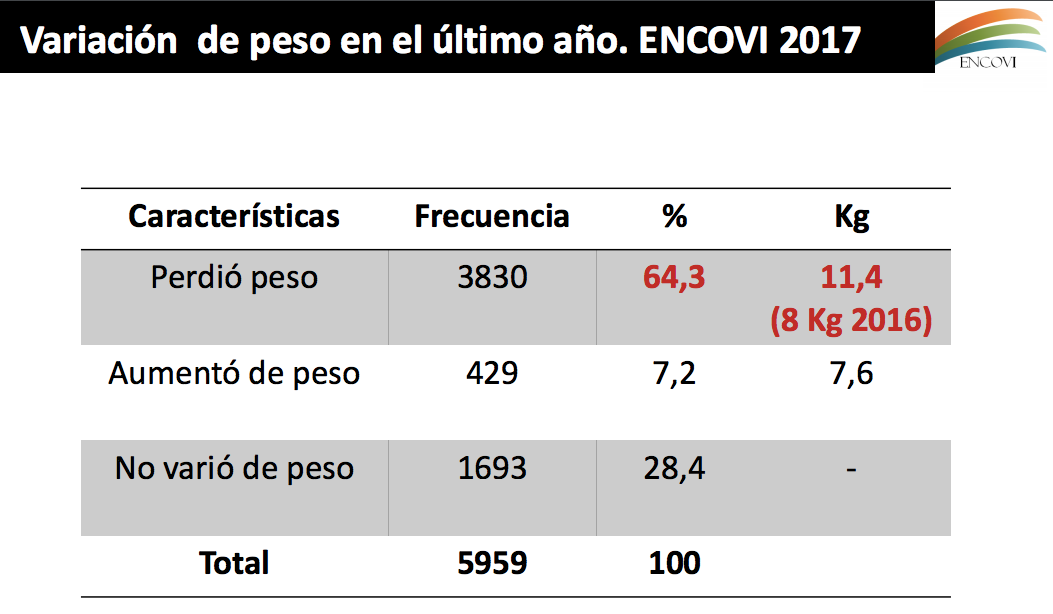

A low protein intake means malnutrition. Some other diseases like anemia might increase, as corn flour -enriched- is less available. But even in terms of calories, people can’t afford enough: 64% of respondents are still losing bodyweight.

And while somewhat fewer people report losing weight (64% in 2017, vs. 74% in 2016) those people who are losing weight are losing more weight: 11.4 kg., vs. 8.9 kg. The year before.)

Health

Health

Venezuela’s performance on maternal deaths is cataloged as the worst in Latin America since 1998.

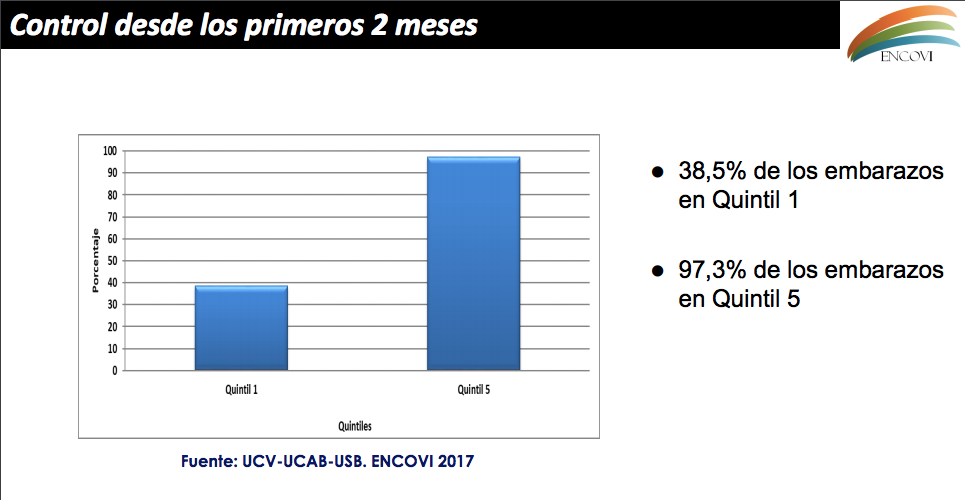

While most of prenatal care is given at public hospitals or outpatient clinics, 45% is done privately. A very large number considering it is the state’s responsibility to provide mechanisms that serve as protection for women’s health. And health inequalities persist: women in the poorest quintile are less than half as likely to get a prenatal check in the first two months than women in the best off quintile.

The survey also found over 68% of people don’t have medical insurance: We are dealing with a crippled public health system and also with most of the population being financially unprotected to cope with disease and its complications.

The survey also found over 68% of people don’t have medical insurance: We are dealing with a crippled public health system and also with most of the population being financially unprotected to cope with disease and its complications.

Dependence

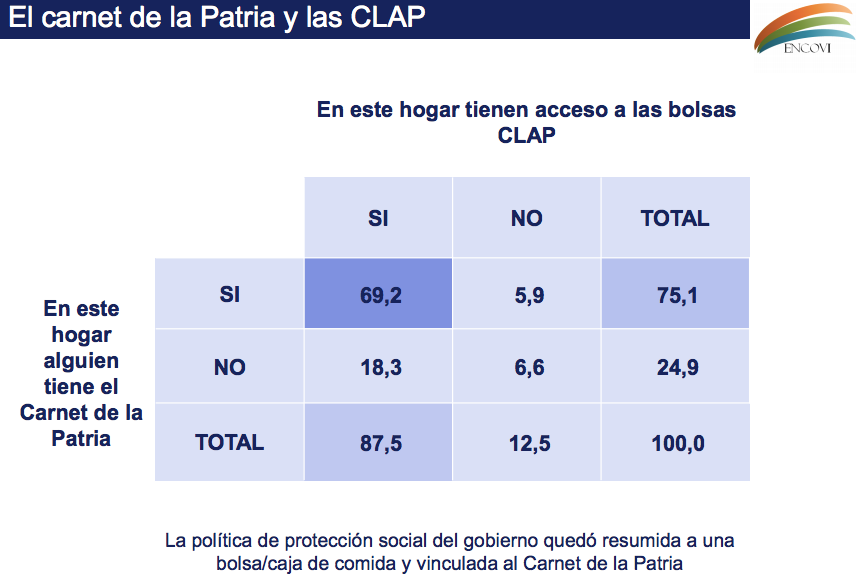

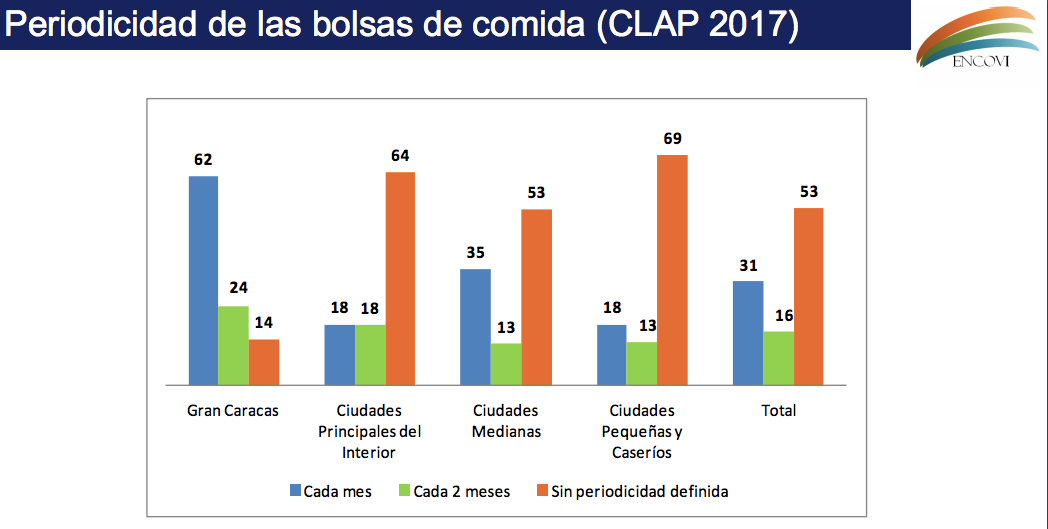

What’s really shocking is the conjunction of income poverty with dependence on state-subsidized food distribution. A staggering 87.5% of households now receive CLAPs subsidized food handouts:

ENCOVI won’t come out and quite say it, but we will: a country where almost nobody can afford to buy enough food at market prices and almost everybody depends on politicized food distribution is a country of slaves.

What’s most disturbing is that, if you live outside Greater Caracas, it’s very likely you don’t have any clear idea when the next CLAPs box is coming:

Emigration

Emigration

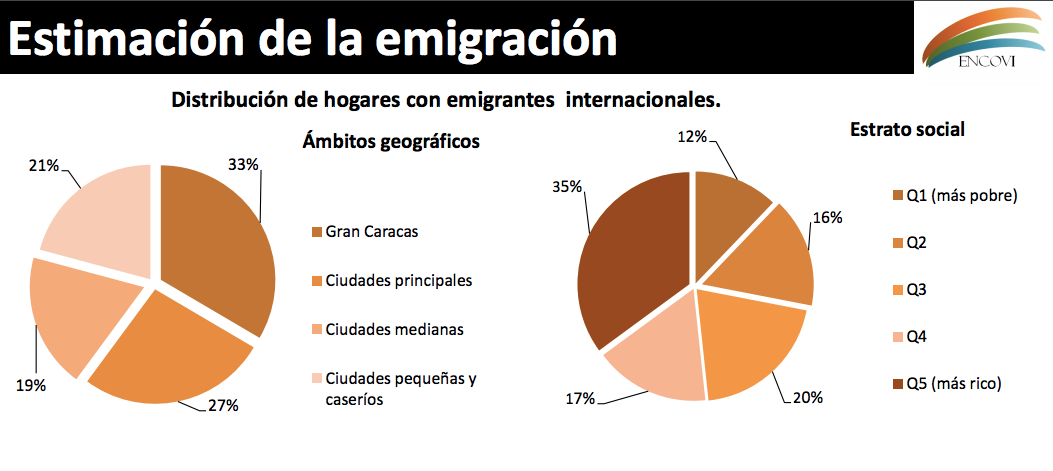

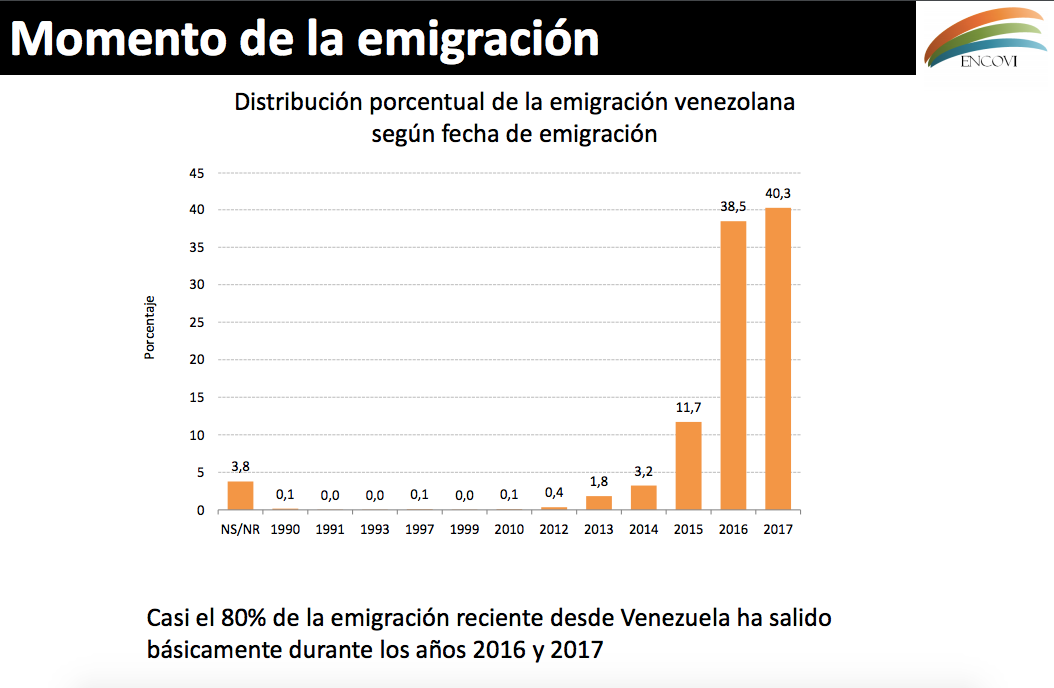

Encovi asked if people have had a member of their families leave the country over the last five years. They actually find somewhat smaller migration numbers than other sources that have been making the rounds. Just 8.5% of households have had, on average, 1.2 members leave the country since 2012. That works out to 815,000 people leaving the country since 2012 — significantly, with the vast bulk leaving in 2016 and 2017.

This is a two-edge sword: it suggests mass migration is barely gotten going thus far. Many, may more people are still around and needing a way out. It won’t surprise you to know that better off people migrate more, as do caraqueños.

This is a two-edge sword: it suggests mass migration is barely gotten going thus far. Many, may more people are still around and needing a way out. It won’t surprise you to know that better off people migrate more, as do caraqueños.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate