Empty Universities

With a massive exodus of both students and professors, and universities struggling with their budgets, Venezuelan academia seems doomed to disappear altogether.

Making my way across campus after a long summer break, I notice the misty, unnatural loneliness. It’s exam season and, after my proceedings in the classroom are done, I look upon the pile of leftover tests. Where did all the students go?

In a country where people struggle to eat, university students are now abandoning their dreams and surrendering to a darker future.

At Mérida’s Universidad de Los Andes (ULA), where I teach, the reasons kids have for dropping out are nothing short of heartbreaking.

I spoke to María, a former third year med student who didn’t come back after the summer break. “Money was a huge reason. Even though our situation is precarious, I was willing to fight for my university and defend it. But paying rent, food and everything else, you can’t fight or study.”

She left for Ecuador to help support her family. This doesn’t mean she is giving up on becoming a doctor. “I didn’t drop out. I know I can become a doctor, whether I am in Venezuela or not.”

Like María, many of my students left, despite being deep into their coursework. Back in 2016, ULA’s secretary, Professor Andérez, warned about the increased drop-out rates of both students and professors. “There’s another kind of desertion. Out of 100 students admitted, 30 don’t show up the first day of class.”

After four months of protests, an installed National Constituent Assembly, a call to vote for governors and a summer break, reports of a drop-out epidemic at ULA are rampant.

I was willing to fight for my university and defend it. But paying rent, food and everything else, you can’t fight or study.

The phenomenon is widespread. Universidad del Zulia (LUZ) has no official numbers, just estimates, with reasons common to all students across the country: crime on campus, weakened benefits like college dining, transportation, accommodation and scholarships, and the rising cost of all basic services and food. The same happens at Barquisimeto’s Universidad Centroccidental Lisandro Alvarado (UCLA), which reportedly closed the 2016 academic year with the worst dropout rate in its history. This year, the traditional intensive courses were not offered as an estimated 30% of students dropped out.

Caracas’s Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV) headmaster, Prof. Cecilia García Arocha, has been warning about the alarming dropout since 2016. “In a faculty where 500 students are admitted, over 100 end up leaving.” Recent figures show that in some cases, like the School of Economics, half the students are gone.

At Universidad Metropolitana (UNIMET), Director of the Liberal Studies dept., Prof. Guillermo Tell Aveledo says they’ve lost about 34% of the students in his department, and that they now have the lowest registration numbers since 2010. “UNIMET is cheaper today than it used to be, if you look at it from the foreign currency perspective. We make efforts to include scholarship recipients and try to keep the professors’ wages updated against the current inflation.”

Por Amor al Arte

And then there are the professors. Colleagues often say they are still here just “por amor al arte;” at UCV, an estimated 50 teachers leave each faculty, every year.

Back in 2013, the Venezuelan federation of university professors (FAPUV) was in deep conflict with the government over the collective bargaining agreement. During three months, classes were cancelled and there was even a hunger strike. Caracas Chronicles turned the coverage into a whole theme week (which is worth taking a look at, very little has changed since).

In the end, FAPUV reached a compromise with the government after it promised to install roundtables, a promise which it promptly disregarded. The government doesn’t even acknowledge FAPUV as a legitimate organization. Collective bargaining agreements have been discussed with a parallel federation in an arrangement that groups professors with administrative and labor personnel. After showing discontent again this year, FAPUV got invited to negotiate the third collective bargaining agreement since 2013, but refused to attend the meetings under these considerations.

Three years ago, Professors worried because they couldn’t afford books, today they worry about food.

I spoke to Prof. Tulio Ramírez, former coordinator of UCV’s Doctorate Program on Education, to know more about the reasons for the exodus of professors.

There are three main reasons: miserable wages, deplorable working conditions and the overall anguish of living in a country this dangerous.

“A full time, upper tier professor earns about $40 a month. The basic food basket is $280. Three years ago, Professors worried because they couldn’t afford books, today they worry about not affording food.”

Universities work on a hunger budget, so seemingly less important expenses get cut off. “We used to have an online bibliographic database. Research doesn’t get financing; the amount assigned by UCV to fund a project in late 2016 was Bs. 30,000 (minimum wage was Bs. 27,000).”

“I have my resignation on a USB drive, ready to print,” says another UCV Professor I spoke to. “We’re living on borrowed time.”

The Bigger Picture

Some other numbers are troubling.

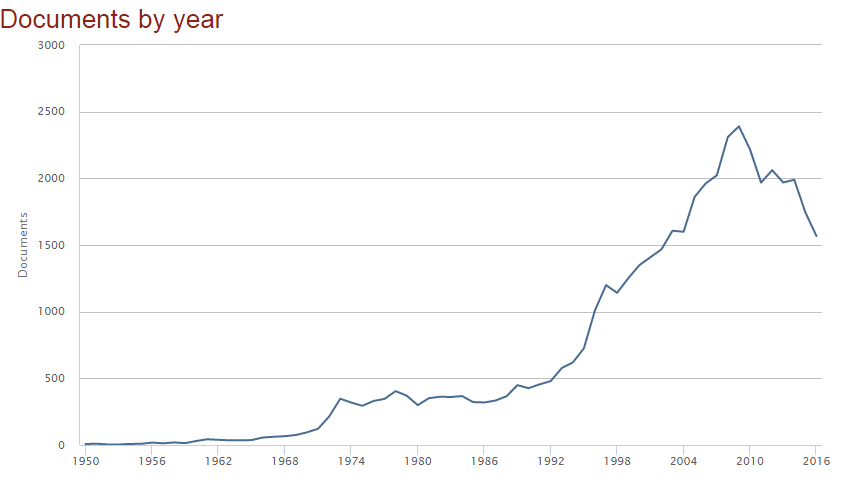

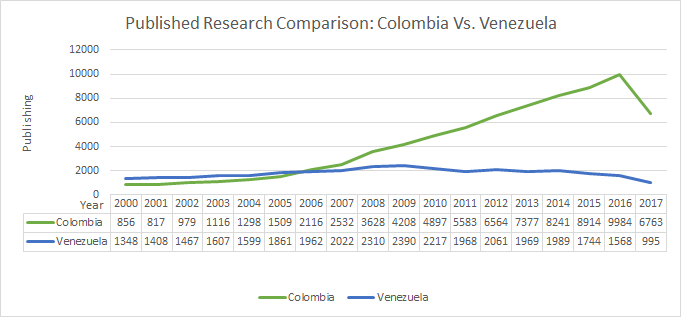

Venezuelan scientific research is falling. When compared to Colombian research, results are dramatically underwhelming (Source: Scopus).

Historically, research is done at autonomous Universities. With not enough financing and an unmanageable crime wave on campuses, it’s no wonder that senior professors, who usually have the experience needed to publish, are fleeing the country. Nothing reflects the bigger picture like the published research in numbers… and it’s not pretty.

On The Verge

The government is, as usual, in total denial, repeating that ever since the Revolution arrived, university enrollment went up 223%. As if finding a spot at a university means that you can afford it.

The regime, by will or ineptitude, is destroying national academia. The campuses where ideas were born and talents blossomed are becoming a mockery of themselves. Empty seats fill classrooms and near-abandoned quads are an increasingly common sight. What hurts the most is that the undermining of universities hits harder on the less privileged. If nothing is done, education will be a right reserved only for the elites.

Just like the revolution said it always was.

__

Santuario de ideales donde la lucha esgrime

Sus portentosas armas con fin derrocador

Donde el sudor es sangre y el corazón no gime

Para alcanzar la cima con paso vencedor

– Himno de la Universidad de los Andes.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate